Dante Alighieri’s The Inferno, the first part of his epic poem The Divine Comedy, is a profound exploration of sin, punishment, and redemption. Written in the early 14th century, it reflects the theological and philosophical perspectives of its time, particularly within the Roman Catholic tradition. How ought we to read this classic from a Lutheran perspective?

Theological Foundations

In short, Lutheranism is rooted in the principles of sola Scriptura (Scripture alone), sola fide (faith alone), sola gratia (grace alone), and solus Christus (Christ alone). What these principles emphasize is that Scripture is the ultimate authority in matters of faith and doctrine (sola Scriptura), justification by faith alone (sola fide, which is often called the material principle of Lutheran dogma), and salvation as a gift of God’s grace alone through Christ alone (sola gratia, solus Christus), independent of human merit. Furthermore, glory is to be given to God alone (soli Deo gloria).

In contrast, Dante’s work is deeply entrenched in the medieval Catholic understanding of sin and salvation, heavily influenced by the scholasticism of figures like Thomas Aquinas. Dante’s journey through Hell, guided by the Roman poet Virgil, is a representation of the soul’s journey toward God, with Hell serving as a stark illustration of divine justice.

Scholasticism, a medieval school of thought that sought to reconcile Christian theology with classical philosophy—particularly that of Aristotle—was the dominant intellectual framework of Dante’s time. Aquinas had integrated Aristotelian philosophy with Christian doctrine in a systematic and rational manner, profoundly shaping medieval Christian thought. (Side note: in 1518, Martin Luther’s Heidelberg Disputation would heavily criticize the Papacy’s utilization of Aristotelian logic.)

Aquinas’ scholasticism is characterized by its methodical approach to theology, emphasizing reason, systematic analysis, and the synthesis of faith and reason. In The Inferno, Dante reflects these scholastic principles through his structured and detailed portrayal of Hell, where he categorizes sins and their corresponding punishments in a systematic way.

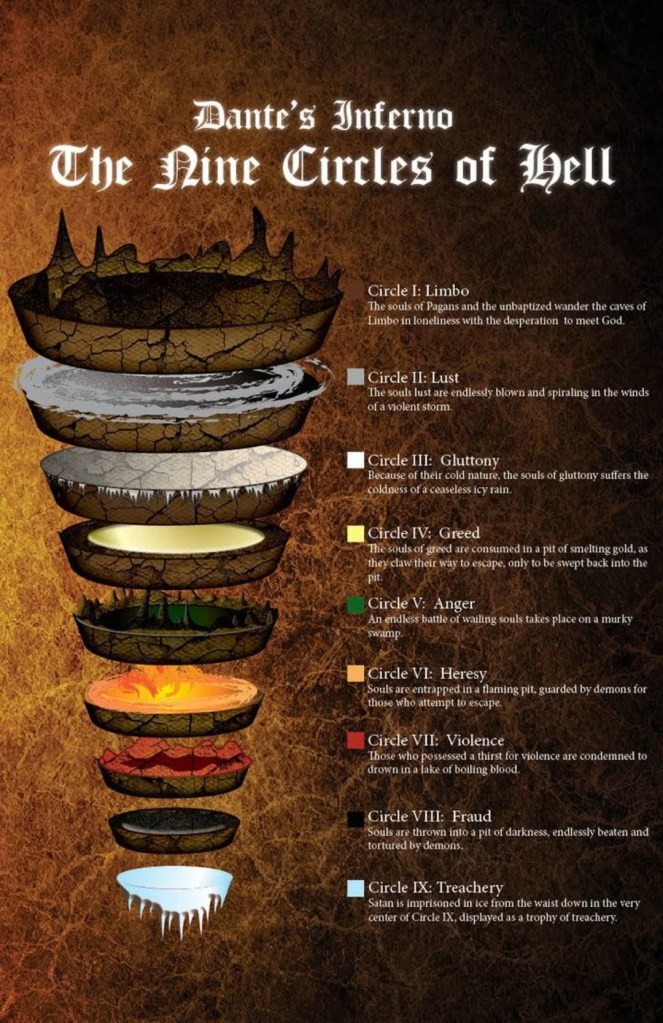

Dante’s Hell is divided into nine circles, each representing different categories of sin with punishments that correspond to the nature and severity of the sins committed, in order: limbo for the unbaptized and virtuous pagans, lust for the lascivious and adulterous, gluttony for the over-indulgent on food and other worldly pleasures, greed for the materialistic and hedonistic (whether they hoarded their possessions or lavishly spent it), anger for the wrathful, heresy for the heretics, violence for the murderers and similar sins, fraud for the fraudulent (e.g., sexual procurers, seducers, those who commit simony), and treachery for betrayers such as Cain and Judas Iscariot.

Aquinas’ Summa Theologica meticulously categorizes sins into mortal and venial and discusses their consequences, a concept Dante adapted into his poetic vision. As Lutherans, we read this not as a faithful depiction of Hell since the Scriptures do not speak of Hell in the way Dante presents it. Instead, we can read it as entertaining fantasy.

Sin and Punishment

As already noted, Dante meticulously categorizes sins and their corresponding punishments, structured according to the severity of the sins, which reflects the Catholic doctrine of the time, including concepts such as Purgatory and the gradation of sins into mortal and venial.

From a Lutheran perspective, this intricate system of sins and punishments is viewed as overly legalistic. Lutheran theology emphasizes the universality of sin (Romans 3:23) and the reality that all sins, regardless of their human-perceived severity, separate humanity from God and are punishable by death. While Dante’s work reflects a belief in a tiered system of justice, as Lutherans we stress that any sin warrants eternal separation from God (e.g., both a liar and a murderer receive the same sentence). We also emphasize that salvation through faith in Christ—redemption from our sins and reconciliation to God—is free, regardless of how high or low the severity of one’s sins might be according to human reason.

Justification and Grace

One of the central critiques from a Lutheran perspective would be Dante’s portrayal of salvation and the role of human merit. The Inferno often emphasizes the consequences of moral and ethical failings, suggesting one’s actions in life directly influence their eternal fate. This aligns with the Catholic emphasis on works and merit in addition to faith.

As Lutherans, however, we believe salvation is granted solely through faith in Jesus Christ, independent of human works. Ephesians 2:8-9 underscores this, “For by grace you have been saved through faith, and that not of yourselves; it is the gift of God, not of works, lest anyone should boast.” Verse 10 continues to emphasize that we were created for good works, not saved by them. Our good works, which God prepared beforehand in His foreknowledge, follows our justification by faith, not the other way around. This crucial doctrine of the Church is missing in Dante’s Inferno.

Purgatory and Hell

In The Inferno, Dante does not delve into Purgatory, as it is the focus of the second part of The Divine Comedy, but his worldview is shaped by this belief. Purgatory, in Catholic doctrine, is a state of purification for souls who have died in a state of grace but still need to undergo purification to enter Heaven.

We reject this as Lutherans because (1) this doctrine is not based on Scripture, and (2) the idea of Purgatory is inconsistent with Scripture’s teaching that the soul either goes directly to Heaven (for the believer) or Hell (for the unbeliever), not an intermediate state or place. (Catholics will say Purgatory is in Scripture, citing 2 Maccabees 12:39-45. But we don’t acknowledge the Apocrypha as Scripture because, in short, they are not divinely inspired and they contradict Holy Scripture. We acknowledge them as historical documents, however. Even the Jews do not recognize these texts as Scripture because, in their view, the Holy Spirit ceased speaking through the prophets after Malachi.)

Hebrews 9:27, for example, says, “And as it is appointed for men to die once, but after this the judgement…” Regarding the fate of Christians specifically, we can look in three places. The first is Luke 23:43, where Jesus says to the believing thief on the cross, “Assuredly, I say to you, today you will be with Me in Paradise.” In the hour of his death, Stephen said, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit” (Acts 7:59). And Revelation 14:13, “Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on.” Entering a place for an undetermined period of time for continued suffering is not a blessed state.

Here are some notable quotes from our Confessions concerning the Lutheran view on Purgatory:

- “The third act of this play, concerning satisfactions, remains. It contains the most confused discussions. The adversaries imagine that eternal punishments are switched to the punishments of purgatory and teach that a part of them is forgiven by the Power of the Keys and that a part is to be redeemed by means of satisfactions. Further, they add that satisfactions should be extraordinary works (supererogation). They make these consist of most foolish observances, such as pilgrimages, rosaries, or similar observances that do not have God’s command. Then, just as they redeem purgatory by means of satisfactions, so a scheme was created for redeeming satisfactions, which was most abundant in revenue. They sell indulgences, which they interpret as the pardon of satisfactions. This revenue is not only from the living, but is much more plentiful from the dead. Nor do they redeem the satisfactions of the dead only by indulgences, but also by the sacrifice of the Mass” (Ap XII, 13-15).

- “For the following teachings are clearly false and foreign, not only to Holy Scripture, but also to the Church Fathers: 1. Through good works, apart from grace, we merit grace from the divine covenant. 2. We merit grace by attrition. 3. Merely hating the crime is enough for the blotting out of sin. 4. We obtain forgiveness of sins because of contrition, and not by faith in Christ. 5. The Power of the Keys provides the forgiveness of sins before the Church, but not before God. 6. Sins are not forgiven before God by the Power of the Keys; rather, the Power of the Keys has been set up to transfer eternal punishments to temporal, to put certain satisfactions upon consciences, to set up new acts of worship, and to put consciences in debt to such satisfactions and acts of worship. 7. The listing of offenses in Confession, as taught by the adversaries, is necessary according to divine right. 8. Canonical satisfactions are necessary for redeeming the punishment of purgatory, or they benefit as a compensation for blotting out guilt. This is how uniformed persons understand it. 9. Without a good disposition on the part of the one using it, that is, without faith in Christ, the reception of the Sacrament of repentance by the outward act (ex opere operato) obtains grace. 11. Our souls are freed from purgatory through indulgences by the Power of the Keys. 11. In the reservation of cases, not only canonical punishment, but also the guilt, should be reserved for one who is truly converted” (Ap XII, 16-27).

- “Nevertheless, the adversaries admit that satisfactions do not help in the pardon of guilt. They imagine that satisfactions help in delivering one from punishment, whether of purgatory or other punishments. They teach that God pardons guilt in the forgiveness of sins. Yet, because divine justice requires sin to be punished, He transfers eternal punishment into temporal punishment… That would mean that satisfactions are only punishments delivering from purgatory. They say satisfactions benefit, even though they are presented by those who have fallen again into mortal sin, as though indeed the divine displeasure could be appeased by those who are in mortal sin. This entire matter is fake and recently made up without Scriptural authority and the old writers of the Church. Not even Lombard speaks of satisfactions in this way” (Ap XII, 118-119).

- As Lutherans, we say “there is no inner repentance unless it also produces the outward putting to death of the flesh. We say that this is John’s meaning when he says, ‘Bear fruit in keeping with repentance’ (Matthew 3:8). Likewise of Paul when he says, ‘Present your members as slaves to righteousness’ (Romans 6:19); just as he likewise says elsewhere, ‘Present your bodies as a living sacrifice’ (Romans 12:1), and so forth. When Christ says, ‘Repent’ (Matthew 4:17), He certainly speaks of repentance in its entirety, of the entire newness of life and its fruit. He does not speak of those hypocritical satisfactions that the Scholastics imagine benefit by delivering from the punishment of purgatory or other punishments when they are made by those in mortal sin” (Ap XII, 132).

- “If the punishments of purgatory are satisfactions, or ‘satispassions,’ or if satisfactions are a pardoning of the punishments of purgatory, do the passages also command that souls be punished in purgatory? Since this must follow from the opinions of the adversaries, these passages should be interpreted in a new way: ‘bear fruit in keeping with repentance,’ ‘repent,’ that is, suffer the punishments of purgatory after this life” (Ap XII, 136).

- “The adversaries foster needless debates about the pardon of guilt. They do not see how, in the pardon of guilt, the heart is freed through faith in Christ from God’s anger and eternal death. Christ’s death is a satisfaction for eternal death. The adversaries themselves confess that these works of satisfactions are works that are not required, but are works of human traditions, of which Christ says that they are vain acts of worship (Matthew 15:9). Therefore, we can safely affirm that canonical satisfactions are not necessary by divine Law for the pardon of guilt or eternal punishment or the punishment of purgatory” (Ap XII, 147).

There are more, but these should suffice.

Concerning Hell, what do Lutherans believe? There are varying opinions on what Hell is: it is either (a) eternal separation from God or (b) a place of eternal torment. Many opt for the former because of the terrifying implications of the latter. Yet as Lutherans, we affirm both positions.

Scripture speaks of Hell as a definite place. “So they and all those with them went down alive into the pit; the earth closed over them, and they perished from among the assembly” (Numbers 16:33). In the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus where the rich man goes to Hell, Abraham says to the rich man, “between us and you there is a great gulf fixed,” and the rich man begs Abraham to send Lazarus to his brothers, “lest they also come to this place of torment” (Luke 16:26, 28). Christ “went and preached to the spirits in prison” (1 Peter 3:19), and other passages. Lutheran theologian Johann Gerhard is worth quoting here:

From the distinction, Scripture distinguishes that place into which the souls of the faithful are gathered after death from that place into which the souls of the ungodly are transferred… The same Scripture distinguishes the location of eternal blessedness, glory, and happiness from the location of the damned and does not place into one room, so to speak, those who enjoy the blessed sight of God together with those who are said to have been cast away from God’s presence into outer darkness. Matt. 8:11-12: The godly along with the patriarchs ‘will recline in the kingdom of heaven, but the children of the kingdom will be cast out into darkness.’ Matt. 25:[32]: ‘He will separate the sheep from the goats’ (never again to be mixed together with them). Luke 16:26: ‘A vast gaping chasm’ (μέγα χάσμα, from χαίνειν, ‘to be wide open and gaping’) ‘has been fixed,’ and thus has been said to have been placed between the blessed and the damned. Rev. 22:15: ‘Outside of, beyond the limits of, the heavenly Jerusalem are the dogs, sorcerers,’ etc.

Gerhard, pp. 209-210

Lastly, “Scripture mutually and directly contrasts heaven as the highest and loftiest palace and hell as the lowest and meanest prison with respect to us” (Gerhard, p. 210). Whereas Korah, Dathan, and Abiram descend to Hell (Numbers 16:33), Elijah is taken up into Heaven (2 Kings 2:11). Speaking of Lucifer, “Hell from beneath is excited about you… For you have said in your heart: ‘I will ascend into Heaven'” (Isaiah 14:9, 13). “For a fire is kindled in My anger, and shall burn to the lowest hell” (Deuteronomy 32:22). Jesus says, “And you, Capernaum, who are exalted to Heaven, will be brought down to Hades” (Matthew 11:23). “The devil, who deceived them, was cast into the lake of fire and brimstone where the beast and the false prophet are. And they will be tormented day and night forever and ever” (Revelation 20:10). And so on.

So, is Hell separation from God or a place of eternal, fiery torment? Yes, for sin and evil have no place in His presence, and He has promised to destroy them.

The Role of Human Reason

Dante’s choice of Virgil—a symbol of human reason—as his guide through Hell is another aspect we would criticize as Lutherans. While reason and intellect have their proper place, our theology emphasizes the limits of human reason in matters of divine revelation and salvation. Faith, rather than reason, is paramount in our understanding of soteriology. Speaking on Matthew 16:13-17, Luther writes:

Christ is confessed here in two ways. First He is confessed according to His life. The disciples say to the LORD, “Some say You are John the Baptizer, others that You are Elijah. Some that You are Jeremiah or one of the prophets.” That is not yet a sure and rightly fashioned confession of Christ. It hangs only onto His outer appearance and the kind of life that Christ led. Many Jews confessed Him that way. So where there is only flesh and reason, people can grasp nothing more of Christ than that he is only a holy, good man who gives us a fine example which we should follow…

Now heaven is still closed to whoever takes Him as a holy man, as an example to be followed for a good life. He has not rightly grasped or confessed Christ. He only regards Him as a holy man, as also Elijah, Elisha, Jeremiah and other good saints had been… Where just plain reason appraises Christ He will only be regarded as a teacher and a holy man. But that is because it is not the Father, but one’s own reason, who is teaching his heart. The other understanding of Christ is the one Peter has when he says here, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.” He is saying, “You are a different kind of man. You are not like Elijah, nor John, nor Jeremiah nor anyone else who has come before. There is something greater about You. You are Christ, Son of the living God. You are beyond comparison to any saint, not to John nor to Elijah, nor to Jeremiah.”

For if Christ is regarded only as a good man, then reason is in control tossing you to and fro, flitting from one to another, from Elijah to Jeremiah. But here He is singled out and regarded as something different than all the other saints. By this He is made sure. For if I have a dubious Christ then my conscience can never be settled. It can never find security.

Basely, pp. 30-31.

In conclusion, we can enjoy Dante’s The Inferno as a genius piece of literature, recognizing he was working within the theological framework of his time, but also recognizing it was written during a time where the Church gave too much credence to Aristotelian philosophy and human reason. The Inferno may be largely responsible for Hollywood’s portrayal and many Christians’ beliefs that Satan is the ruler of Hell. Neither is it meant to scare people into believing in God, as atheists like to retort. Rather, God is the ruler of Hell (Matthew 10:26-33) and that it is Satan’s doom, not his kingdom (Matthew 25:41; Revelation 20:10). Hell is not a scare tactic to get people to believe in God; it is simply the reality of where sin, evil, Satan and his demons, and evildoers will dwell since sin and evil have no place in God’s holy presence (Psalm 5:4-5). It is God’s righteous way of dealing with evil and evil people. Only evil people would complain about their just fate. Rather than complaining about it, they should repent so that they may live (Ezekiel 18:23).

Bibliography

Baseley, Rev. Joel. Christ Beyond Reason: Luther’s Treatment of Faith and Reason in the Festival Portions of the Church Postils. Dearborn, MI: Mark V Publications, 2005.

Gerhard, Johann. On the End of the World, and On Hell, or Eternal Death. Edited by Joshua J. Hayes and Aaron Jensen. Translated by Richard J. Dinda. Theological Commonplaces. Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2021.