I love The Lord of the Rings. It’s a sweeping epic—a saga of travail through shadowed valleys, encompassing both interior battles of the soul and the cataclysmic clashes of armies. As a theologian, I could easily revisit familiar terrain and expound on Tolkien’s rich depiction of humanity’s struggle with darkness, drawing parallels between Middle-earth’s encroaching shadow and our own contest with sin. In fact, I have already done so with Geeks Under Grace. So instead, I wish here to highlight something far less commonly examined: the profound and unembarrassed friendship between Samwise Gamgee and Frodo Baggins.

In recent years, I’ve encountered no shortage of fatuous theories alleging that Sam and Frodo must be closet homosexuals. Their reasoning, if one can call it that, is painfully reductive: Because these two men share a bond of uncommon tenderness and vulnerability, it must necessarily be romantic or erotic. In a culture that relentlessly sexualizes every form of intimacy, such conjecture is regrettably predictable. Contemporary society has grown increasingly incapable of imagining that two men might embrace, weep together, or even kiss one another on the brow in a wholly non-sexual manner. The idea that Sam might literally carry Frodo—body, burdens, and all—up the deadly slopes of Mount Doom out of sacrificial love seems unintelligible to a modern imagination conditioned to reduce every affection to erotic impulse.

But we must ask: Is their affection secretly homoerotic, or is it instead a luminous example of deep, virtuous, and distinctly masculine friendship? I contend the latter. Sam and Frodo illustrate a form of masculinity that is courageous, self-giving, emotionally honest, and unafraid of embodied tenderness. Because I write as a man, and because Tolkien’s protagonists are men, I will consider specifically the nature of male friendship, while acknowledging, of course, that the same virtues apply across the spectrum of all human relationships.

By “masculinity” I most assuredly do not mean the caricature offered by modern culture: the posturing bravado of men who equate strength with emotional suppression, or who define themselves by physical dominance, growling aggression, or superficial markers such as bodybuilding and sports fandom. That is a counterfeit masculinity—fragile, insecure, and spiritually malformed. True masculinity is the character of a godly man: one who sacrifices, who speaks truth for the good of his brother, who endures hardship for the sake of the relationship, and who is unashamed to express love openly and chastely. It is this masculinity—the biblical variety—that Sam and Frodo embody with remarkable clarity.

Friendship as Sacrifice

One of the defining marks of true friendship is a willingness to sacrifice. As St. Paul admonishes, “Let nothing be done through selfish ambition or conceit, but in lowliness of mind let each esteem others better than himself” (Philippians 2:3). Christ Himself is our ultimate example: His every act was characterized not by ulterior motive but by radical self-emptying on behalf of those who could never earn it.

Sacrificial friendship doesn’t deny our legitimate needs for rest, nourishment, or safety. Rather, it orders our desires so that our neighbor’s needs take precedence over our comforts. Christ met humanity’s deepest need—deliverance from condemnation—through the supreme sacrifice of His own life. In Middle-earth, Frodo mirrors this pattern sacramentally: he relinquishes his own safety, comfort, and peace for the salvation of others.

And Sam? Sam forfeits the simple life he cherishes, choosing instead to walk willingly into peril because he sees his friend’s need. He could have remained in Rivendell, sheltered from danger, or gone back to the Shire. Yet love compelled him into hardship.

This raises a searching question for us men: When our friends are burdened, do we shrink back into the shadows, or do we stretch beyond our comfort to shoulder their load? True friendship requires vulnerability, and vulnerability can be terrifying, especially for those of us marked by rejection, abandonment, or betrayal. For much of my adult life, I’ve attempted to handle everything alone. But isolation isn’t strength; it’s a wound masquerading as independence. To be trustworthy, we must act in ways that demonstrate trustworthiness—by sacrificing our comforts for another’s welfare.

God places specific people in our lives for precisely this purpose. They’re called friends. Through them, He ensures we do not bear our burdens alone.

Friendship as Truth-Telling

A man speaks up. By speaking up, I don’t merely mean defending a friend from insult, though that too is honorable. I mean something costlier: confronting a friend with his sin, folly, or self-deception. Silence in such moments isn’t kindness but cowardice. Fear of losing the relationship often muzzles us, but if a friendship collapses because we urged someone to “go and sin no more” (John 8:11), then it wasn’t a friendship rooted in virtue.

True friends admonish one another, and true friends receive admonishment with humility. Christ Himself corrected His disciples—whom He called His friends (John 15:15)—repeatedly, including when they attempted to prevent infants from being brought to Him (Luke 18:15-16). Jesus rebuked their spiritual blindness, insisting that even the smallest and weakest must be received into His kingdom.

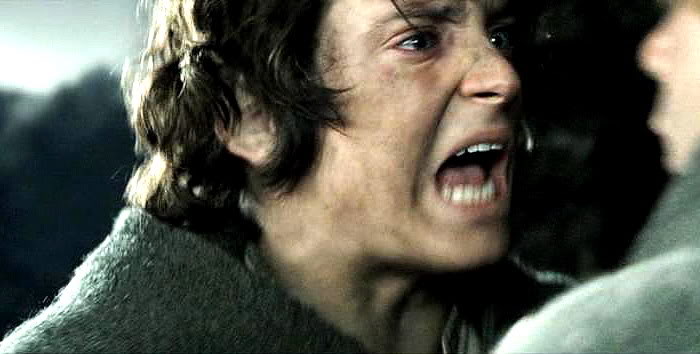

A parallel moment occurs in Tolkien’s narrative. Sam discerns Gollum’s duplicity long before Frodo does. Out of love, he warns Frodo—pleads with him—to see the danger. Frodo, clouded by the Ring’s influence and his misplaced trust, rejects Sam’s counsel and even banishes him. Yet Sam was the faithful friend; Frodo, blinded and hurting, was not.

How often do we likewise see a friend sliding toward destruction yet remain silent? Are we too timid to risk the discomfort? Too anxious to jeopardize the relationship? To cowardly to be seen as virtuous? Be like Sam—willing to risk losing the friendship for the sake of truth, that is, their own welfare. And when we ourselves are admonished, let us not imitate Frodo’s moment of folly. Receive correction as the painful but necessary expression of love that it is.

Friendship as Perseverance

I speak here not of individual endurance but relational perseverance. Every genuine friendship will encounter seasons of strain—misunderstandings, disagreements, and even betrayals. Saint Peter reminds us that the devil prowls around like a predator, seeking to devour not only individuals but relationships as well (1 Peter 5:8-9).

Because of my own history of betrayal, I know how fragile friendships can feel. Some relationships in my life were damaged beyond repair; others were redeemed through repentance and forgiveness. One such friendship—now spanning well over two decades—was salvaged only because both of us possessed enough humility to name our wrongdoing, and it began with yours truly forcing himself to recognize his grave error.

So, too, with Sam and Frodo. Frodo’s dismissal of Sam was a grave wound in their fellowship. Yet when Frodo recognized his error after Gollum’s betrayal, he sought Sam’s forgiveness. And Sam, with characteristic mercy, granted it. Both men humbled themselves—the one to repent, the other to forgive (cf. Matthew 18:15-20).

This raises another pressing question: When a friendship fractures, do we pursue reconciliation? Do we repent when we’re at fault? Do we forgive when asked? Christ commands a forgiveness that knows no numeric limit (Matthew 18:21-22), for God Himself forgives us immeasurably more times than we can count. A friendship saturated in mercy is a friendship that endures.

Friendship as Love

Human affection isn’t the enemy of masculinity; it is one of its glories. We readily accept emotional warmth between women and don’t hastily classify it as homoerotic, yet we recoil when two men display similar intimacy. The scenes between Sam and Frodo—tearful embraces, mutual consolation, even a chaste kiss on the brow—are not homoerotic. They’re a reclamation of what male friendship once was before the debasement of modern imagination collapsed all affection into sexuality.

In Scripture, Christians were exhorted to “greet one another with a holy kiss” (Romans 16:16)—a sign of fellowship, not sexual desire. Certain cultures today retain non-sexual gestures of affection between both genders, yet in the West, such expressions are now viewed with suspicion. Our culture has lost the vocabulary for platonic intimacy.

Real friendship requires emotional openness. Friends mourn together, rejoice together, and share the weight of each other’s struggles. I cherish the joy and honesty I share with certain brothers in my life, whether through theological conversation, shared hobbies, or mutual confession of the battles we face. These bonds, forged in vulnerability and strengthened in compassion, resemble in a modest way the fellowship of Sam and Frodo.

Our society has sexualized what God intended to be holy, tender, and fraternal. It’s not the intimacy that’s perverse, but the cultural lens that misinterprets it.

Conclusion

Friendship demands more than casual association. It is characterized by sacrificial love, courageous truth-telling, steadfast perseverance, and unembarrassed affection. Without these virtues, what we call “friendship” is little more than proximity. True friendship is its own form of deep, spiritual intimacy—not erotic, but covenantal. It’s the willingness to shoulder another’s darkness, to bear his burdens, to forgive freely, and to rejoice in his very existence. Only a culture impoverished by lust would assume such love must be sexual. Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer writes most excellently on this Christian brotherhood:

[The Christian] must suffer and endure the brother. It is only when he is a burden that another person is really a brother and not merely an object to be manipulated. The burden of men was so heavy for God Himself that He had to endure the Cross… But He bore them as a mother carries her child, as a shepherd enfolds the lost lamb that has been found… In bearing with men God maintained fellowship with them. It is the law of Christ that was fulfilled in the Cross. And Christians must share in this law… what is more important, now that the law of Christ has been fulfilled, they can bear with their brethren.

Life Together, 100-101

Love manifests not in consumption but in sacrifice; not in secrecy but in truth; not in abandonment but in steadfast mercy. In Sam and Frodo, Tolkien offers us an image of masculine friendship at once ancient, biblical, and desperately needed in our world today.

Bibliography

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Life Together. Translated by John W. Doberstein. New York: HarperOne, 1954.