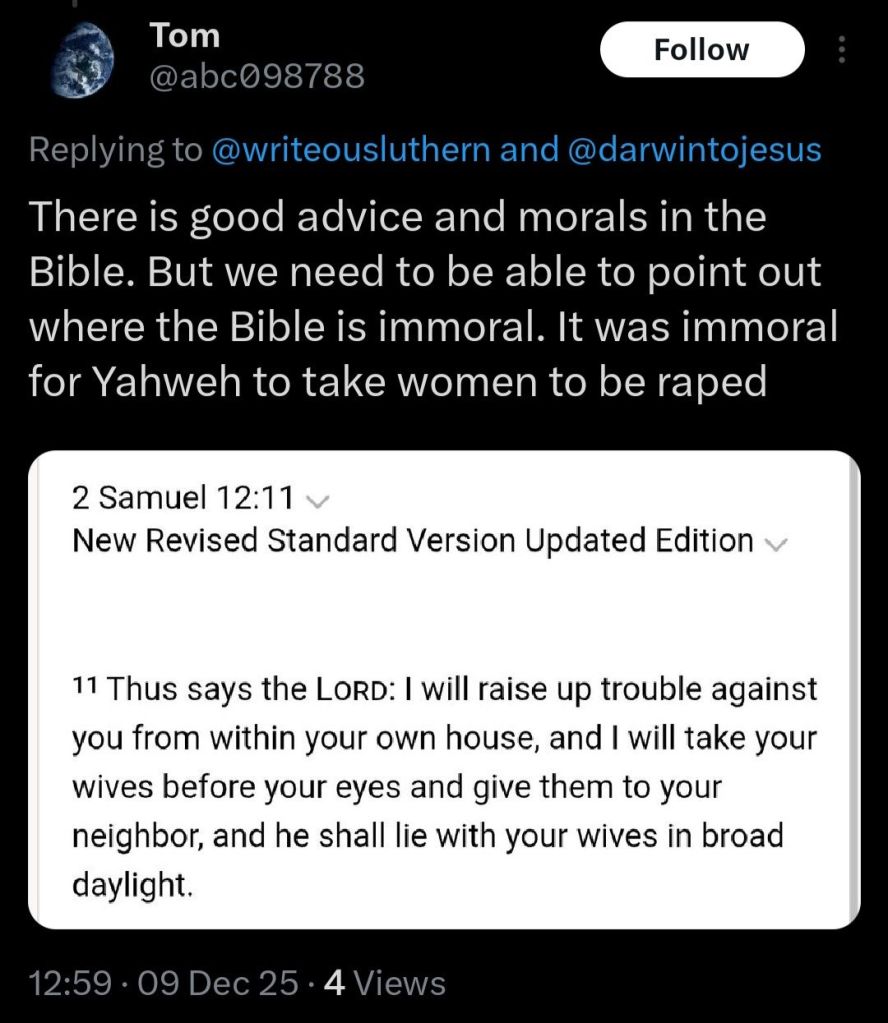

This is simply one of many Scriptures frequently weaponized or misunderstood that critics often seize upon without any regard for genre, narrative flow, or Hebrew idiom, declaring that the God of the Bible must therefore endorse rape or command it. This accusation, while rhetorically inflammatory, is rooted in a shallow reading that isolates a single sentence from its literary and historical context. The above post is a classic example of poor reading comprehension. Far from revealing a monstrous deity, the passage instead reveals a God who deals seriously with the sins of His people—especially the sins of powerful leaders—and who allows judgement to unfold in ways that mirror the very harm a sinner has inflicted on others. When the text is allowed to speak for itself without being forced through the myopic, hostile lens of proof-texting, its meaning is far more coherent, just, and morally consistent than the critics assume.

The Setting: This Is Judgement, Not Prescription

2 Samuel 12 occurs immediately after one of the darkest moments in David’s life. David has abused his royal authority by taking Bathsheba—the wife of Uriah—and committing adultery with her. He essentially rapes her, because how could she say no to the king? When Bathsheba becomes pregnant, David orchestrates the death of her husband, arranging for his loyal soldier to be abandoned on the battlefield (in today’s legal terms, this is conspiracy to commit murder). David then quickly marries Bathsheba in an attempt to hide his crime. What appears on the surface to be a pious king simply adding another wife is, in reality, a coverup of adultery and murder. Into this context, the prophet Nathan arrives with a parable exposing David’s sin. When Nathan declares, “You are the man!” (v. 7), the king is confronted not just with guilt but also the devastating consequences of his actions.

Nathan’s prophecy is not a set of moral instructions, neither is it a divine endorsement of the actions wicked men will later commit. It’s a sentence—a judicial announcement of what David’s sin will unleash in his own house. David raped a man’s wife, so now the women of his own household will be raped. It’s poetic justice. God isn’t telling David what to do; He’s telling David what will happen as a direct result of his betrayal of the covenant and his vocation as king. Just as God’s declaration that “the sword shall never depart from your house” (v. 10) doesn’t mean God approves of violence or commands murder, the words of verse 11 don’t express divine approval of sexual sin. They’re a sober pronouncement that David’s private corruption will be exposed in a very public collapse of his household, as God Himself says immediately after, ” ‘For you did it secretly, but I will do this thing before all Israel, before the sun'” (v. 12). Judgement ≠ prescription; consequences ≠ commands; divine sovereignty ≠ moral endorsement. If we fail to distinguish these categories, we’re not reading the text on its own terms.

The Hebrew Pattern: God Often “Does” What He Permits in Judgement

One of the greatest challenges for modern readers is understanding how Hebrew expresses agency. In prophetic judgement oracles, God often says “I will do x” to describe an outcome He brings about by withdrawing His protective hand, not by committing the evil Himself. Hebrew often attributes to God what He allows since He’s the sovereign Judge who oversees history and determines the consequences of sin.

Consider Isaiah 10, where God declares that He “sends” Assyria against Israel. Yet moments later, the prophet makes clear that Assyria acts not from obedience to God but from its own arrogant, destructive ambition (vv. 6-7). God’s “sending” is an act of judgement—He no longer restrains the aggression of a nation already bent on conquest. Similarly, in Romans 1, Paul describes divine judgement as God “giving them over” to the consequences of their desires (v. 24). God judges not by injecting evil into people’s hearts but by allowing them to experience the full weight of their rebellion. This is also reflected in Job 1-2 where God allows Satan to afflict Job, yet the narrative is explicit that Satan—not God—is the one performing the evil actions. God’s sovereignty frames the event; human and demonic agents carry out the wickedness.

This linguistic pattern is essential to reading 2 Samuel 12:11 correctly. When God says, “I will do this,” He’s not claiming to be the moral agent of the wickedness. He’s declaring the sentence, commanding nothing, endorsing nothing, but allowing the consequences of David’s sin to run their course. In a Hebrew worldview, God is the Judge who oversees the outcome; the immediate actors remain fully responsible for their actions. Confusing God’s sovereign announcement of judgement with divine moral approval is a fundamental interpretive mistake.

The Fulfillment: Wicked Men, Not God, Commit the Sin

The fulfillment of Nathan’s prophecy occurs during Absalom’s rebellion in 2 Samuel 16. After years of festering resentment, political maneuvering, and tension within David’s household, Absalom stages a coup. In an explicit act of political theater designed to show he’s completely seized the throne, Absalom sleeps with David’s concubines on the palace roof, mirroring the location where David’s lust for Bathsheba first took root. This act is both public and humiliating—a symbolic declaration that the king’s authority has been completely overthrown. The narrator is careful to show that this action arises from Ahithophel’s wicked counsel and Absalom’s ambition, not from any command of God. God doesn’t tell Absalom to do this. God doesn’t approve of it. God doesn’t “cause” the desire or the treachery. It’s entirely the work of sinful men pursuing power.

This distinction is crucial. If God were truly the one “doing” the act in a literal, hands-on sense, the narrative would depict God instructing Absalom or compelling him to carry out the sin. Instead, Scripture consistently condemns Absalom’s pride, rebellion, and violence. The prophecy is fulfilled through human wickedness, which God permits as the unraveling of David’s house—a direct consequence of David’s earlier misuse of power. What David took privately, his son takes publicly. What David thought he could control, God allows to spiral beyond his reach. The moral agency remains squarely on Absalom and those who aided him, not on God, who remains holy and just.

The Crucial Hermeneutical Point: Describing Sin ≠ Approving Sin

A major fallacy in the accusation that God endorses rape in this passage is the assumption that a description of sin equals divine approval. This is a failure of the most basic of hermeneutics. The Bible frequently describes horrific acts—murder, treachery, assault, idolatry—without every implying God approves them. No one blames the author of a historical book of approving the wicked actions depicted. This rationality is completely thrown out the door when it comes to the historical narratives of the Bible simply because the individual hates God and Christianity. Thus, such accusations are an emotional response, not a rational one, which is ironic considering how much they tout logic and reasoning.

Similarly, if a prophet warns that, because of Israel’s sin, “Your enemies will slaughter your people,” no reasonable reader concludes God endorses slaughter. The same principle applies here. The argument that “God predicted it, therefore He approves of it” is both logically incoherent and inconsistent with how anyone reads any other judgement passage.

Moreover, the very purpose of Nathan’s oracle is condemnation. God is showing David the severity of his sin by letting him see its consequences. Prophetic judgement often mirrors the sinner’s original crime. David took another man’s wife; now his household will be torn apart by sexual sin and rebellion. David acted in secret; now the consequences erupt in public. Again, it’s poetic justice. None of this requires divine endorsement of the sinful acts. To accuse God of approval is to impose a modern, literalistic reading onto an ancient genre without considering how that genre communicates judgement, justice, and sovereignty.

So Why Does God Say, “I Will Do This”?

This question lies at the heart of the issue, and answering it requires understanding how prophetic judgement speeches function. When God says “I will do this,” He’s speaking as the Judge, not the perpetrator. In ancient legal settings, the judge declares the sentence, and in doing so is said to “do” the punishment, even though others carry it out. We use similar language today. When we say, “The judge sent him to prison,” no one thinks the judge personally locked him in a cell or endorses every evil that might occur in the prison system. The judge’s authority frames the event, but the actors within it remain morally responsible for their conduct.

In 2 Samuel 12, God announces the sentence: David’s household will tear itself apart, and the consequences of his sin will be exposed in the sight of all Israel. This doesn’t imply God commands or approves of the sinful acts that occur during Absalom’s rebellion. Rather, God is declaring He will no longer restrain the disaster David’s actions have already set in motion. Judgement is often described as God removing His protecting hand, allowing the sinner to experience the natural and relational consequences of his sin. It is only His grace that prevents such consequences from taking its course. The “I will do this” is judicial language, not ethical endorsement.

The Fallacies Behind the Misreading

Several logical and interpretive fallacies underlie the accusation that God endorses rape in 2 Samuel 12. The first is category error—the confusion of divine judgement with divine command. When critics read “I will do this” as “I approve this,” they merge categories the Hebrew Scriptures keep distinct. Another is wooden literalism, which is the tendency to take every phrase with hyper-literal precision, ignoring the idiomatic and poetic ways ancient languages describe agency, judgement, and sovereignty. This literalism is inappropriate in historical narratives and doubly inappropriate in prophetic oracles, which frequently utilize metaphorical or representative language.

There’s also the classic strawman fallacy where the critic constructs a caricature of the text (“Yahweh takes women to be raped”) and then attacks that caricature rather than the text itself. Coupled with this is proof-texting, which is the practice of lifting a single verse out of its narrative context to “prove” one’s preconceived notion. A responsible reading examines the whole story—David’s sin, Nathan’s rebuke, Absalom’s rebellion, and the theological pattern of divine judgement. Isolating one sentence and insisting on the most inflammatory interpretation does not reflect honest inquiry. It reflects a desire to score rhetorical points at the expense of textual integrity.

What the Passage Actually Shows About God

When read properly, the passage doesn’t showcase a cruel or arbitrary deity. Instead, it displays a God who takes sin seriously, especially when committed by those entrusted with authority, which comes from God (Romans 13:1). So, even worse, the misuse of authority is a personal insult to God, who has authority over all things. David’s actions were not victimless; they shattered households, betrayed trust, and polluted his kingship. The consequences thus reflect the gravity of the offense. This isn’t divine cruelty but divine justice, mirroring the relational and societal devastation David himself caused. If the critic is truly upset by the supposed immorality of God’s pronouncement, then they must accept its opposite moral outcome: that God allow David, whom He personally chose as king, to get away with his rape of Bathsheba and murder of her husband. Which one is more morally outrageous: that God allows David to face the consequences of his sins, or that God do nothing about his heinous crimes against Bathsheba and Uriah?

Furthermore, the narrative reveals a God who remains faithful even in judgement. Despite the chaos of Absalom’s rebellion, God mercifully preserves His covenant with David. He doesn’t abandon the king or revoke His promise to establish David’s line forever (2 Samuel 7:16). The judgement has real, painful consequences, but it doesn’t nullify His grace. The God of 2 Samuel 12 is not a deity who delights in suffering but one who disciplines with purpose, restores after rebellion, and works redemption out of brokenness. The passage ultimately points not to divine endorsement of evil but to the holy seriousness with which God treats sin and the astonishing faithfulness with which He keeps His promises. God never sweeps sin under the rug; He always deals with it seriously, which we see most clearly on the cross.

A Hard Passage, But Not a Cruel God

2 Samuel 12:11 is a difficult passage not because God is unjust, but because sin is devastating. The verse doesn’t depict God commanding or approving rape. It depicts God announcing the consequences of David’s abuse of power and describing, in the idiom of judgement, how the sin he unleashed will now consume his house. The accusation that God endorses the act arises from misreading the genre, purposefully ignoring the narrative, collapsing categories, and interpreting Hebrew idioms with anachronistic, wooden literalism. When the passage is treated with literary and theological care, it becomes clear that God is the Judge who permits consequences, not the perpetrator who commits or approves of sin.

When God says, “I will do this,” He’s not endorsing the evil acts of wicked men; He’s declaring that the protective boundaries of His providence will be lifted and that the natural consequences of David’s sin will unfold. The narrative of Absalom makes this unmistakable. Sin leads to tragedy, rebellion leads to collapse, and the household built on secrecy and exploitation eventually crumbles. Yet through it all—amazingly and unfathomably—God remains faithful, even when we are faithless (2 Timothy 2:13), not because the sin was small, but because His mercy is always greater.