“Surely, you have spoken in my hearing, and I have heard the sound of your words, saying, ‘I am pure, without transgression; I am innocent, and there is no iniquity in me.’” — Job 33:8-9

Speaking to a Sufferer with Reverence

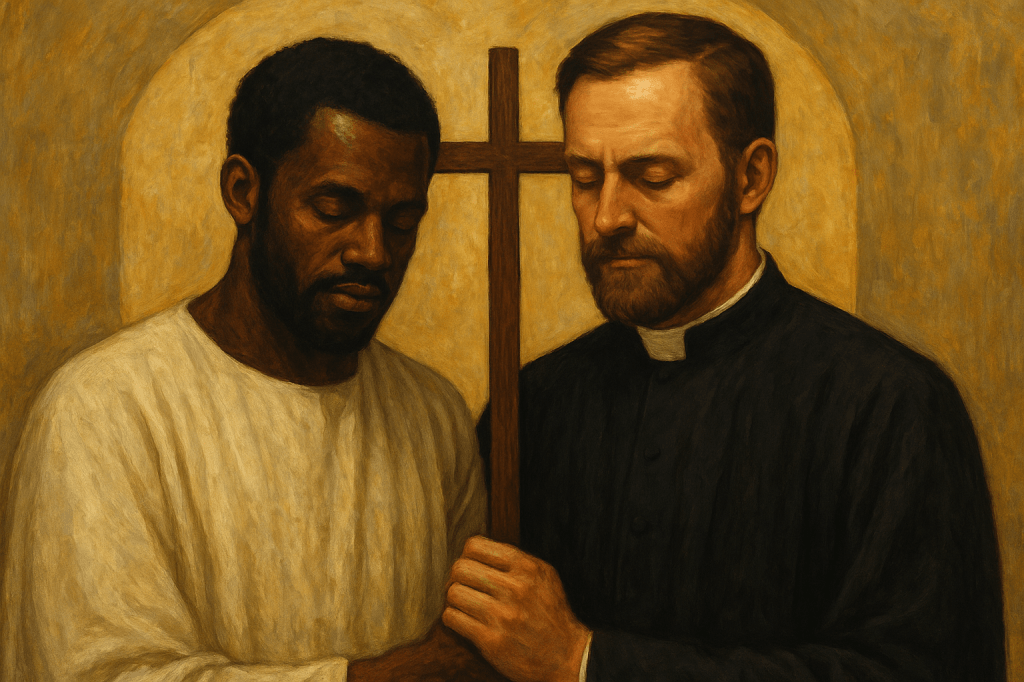

Elihu begins his appeal with gentleness: “But please, Job, hear my speech, and listen to all my words” (v. 1). Unlike the previous friends who were quick to condemn, Elihu invites dialogue. “Truly, I am as your spokesman before God; I also have been formed out of clay” (v. 6). Also unlike the other friends, Elihu approaches Job as a fellow mortal instead of from a position of superiority. He stands not above Job but beside him. This sets a different tone—he speaks not with arrogance but with the seriousness of one who believes truth and grace must walk hand in hand.

He assures Job, “Surely, no fear of me will terrify you, nor will my hand be heavy on you” (v. 7). Elihu wants to be heard, not feared. His goal is to bring clarity, not punishment. He acknowledges Job’s pain and listens carefully to his words. He then repeats them back to him not as mockery but to hold them up for examination: “You have said, ‘I am pure, without transgression’” (v. 9). Elihu’s concern is that Job, in justifying himself, has begun to suggest that God is unjust. Job is a man of integrity, yes, but he has allowed his works of integrity to be his vindication rather than God’s gracious Word (e.g., chapter 29).

If you’ve ever tried to comfort someone in deep pain—or if you’ve been the one suffering—you know how easily words can wound or heal. Elihu reminds us truth must be spoken with reverence and gentleness, even when the words might sound harsh, especially when addressing someone crushed by grief. He does not mock Job. He does not pile on shame. Instead, he speaks as one who shares Job’s humanity. This humility is essential for anyone who dares to speak into another’s suffering. Before we offer correction, we must first offer our shared humanity.

And if you’re the one in pain, Elihu’s gentler tone reminds you that not all correction is condemnation. Sometimes, God speaks through others—not to accuse you but to restore you. There may be moments when someone holds up your words with love and says, “I heard you. Let’s look at this together.” If it comes from humility and grace, receive it not as judgement but as an invitation. God often brings clarity through conversation and healing through those who dare to speak both truth and tenderness at once. Elihu, though imperfect, teaches us truth without love can crush, but truth with reverence can restore.

God is Greater than Man

Elihu gently challenges Job’s logic: “Look, in this you are not righteous. I will answer you, for God is greater than man. Why do you contend with Him? For He does not give an accounting of any of His words” (v. 12). This is the center of Elihu’s theology. He does not say Job is wicked, but that Job cannot claim superior understanding to God’s. Elihu’s words are a reminder that human wisdom cannot grasp divine purposes in full. If God is silent, it’s not because He’s cruel but because He is beyond us. To assert otherwise is to elevate man above his Creator. In this way, we see that although Job is a theologian of the cross, at times he also becomes a theologian of glory, for we are all naturally theologians of glory.

Then Elihu introduces a new possibility—that God may speak in ways we do not recognize: “For God may speak in one way, or in another, yet man does not perceive it” (v. 14). God is not limited to dreams or visions; He may speak through suffering itself. Not all pain is punishment. Sometimes, it’s instruction. Sometimes, it’s mercy in disguise

When Elihu says, “God is greater than man,” he’s drawing Job back to a vital truth: we do not judge God’s character by our circumstances. Back in chapter 23, I talked a little bit about God’s alien work and His proper work. God’s alien work refers to the strange and terrifying things He sometimes does—afflicting, humbling, and even appearing hostile. But these are never His final intention. His proper work is to forgive, heal, and save. Mercy is His delight. Even when He acts in wrath, or permits suffering, it is to make room for grace.

Job is in the midst of experiencing God’s alien work. He feels God’s hand heavy upon him. He perceives only opposition, silence, and sorrow. But what Elihu wants Job to consider—and what the whole arc of Job will reveal—is that God’s alien work is never separated form His proper work. God wounds, but He also binds up, which even Eliphaz acknowledged, despite his error (5:18). God hides His face, but only to awaken deeper trust. When all God’s people hear is His silence, it is not rejection—it is preparation for a deeper revelation.

If you’re enduring similar seasons, this is vital comfort. When God feels distant, when life collapses, and when prayers return unanswered, we must remember God may be working through affliction, but His heart is always bent toward mercy. The cross is the clearest expression of this truth. There, God’s alien work reached its fullest expression—crushing the Righteous One, forsaking His Son, and pouring out His wrath on Him. But all of it served His proper work: redeeming sinners, reconciling enemies, justifying the ungodly, and raising the dead. The cross is where God’s terrifying judgement serves His eternal love.

Therefore, if you, like Job, are enduring a season where God feels like an adversary, hold fast. The work that now humbles you is not His final word. He may strike, but only to heal. He may deconstruct your confidence, but only to rebuild you in grace. God’s proper work is to comfort, not to crush—to restore, not ruin. And in Christ, we see that even when God hides His face, His heart remains full of compassion. The God who is greater than man is also kinder than we can comprehend, for like Elihu He also stands beside us in our suffering through His incarnation. His greatness is finally revealed not in how high He stands above us but in how low He stoops to save us.

Suffering as Redemptive Discipline

Elihu describes how God may use affliction to turn a person from destruction: “Man is also chastened with pain on his bed, and with strong pain in many of his bones, so that his life abhors bread, and his soul succulent food… If there is a messenger for him, a mediator, one among a thousand, to show man His uprightness, then He is gracious to him, and says, ‘Deliver him from going down to the Pit; I have found a ransom’” (vv. 19-20, 23-24). This is a remarkable shift from the earlier accusations of Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar. Elihu sees suffering not only as discipline but as a means through which God spares a person from greater ruin.

At the heart of this view is hope. “His flesh shall be young like a child’s; he shall return to the days of his youth. He shall pray to God, and He will delight in him, he shall see His face with joy, for He restores to man His righteousness” (vv. 25-26). Elihu introduces the idea that God is not only just but also gracious—that He does His alien work to accomplish His proper work, that He disciplines in order to restore, and that pain may bring the sufferer back to prayer, repentance, and healing.

Finally, we have arrived at the point in which I would like to share why I have endeavored to write this pastoral commentary. The Book of Job has always been a mystery to me, as it is for most Christians, I assume. Long before this commentary, it was always my theory that Job’s three friends are theologians of glory and Job himself is a theologian of the cross, and at times a theologian of glory as we all are, even us theologians of the cross. I have had clinical depression for the majority of my life, so this book has always attracted me.

However, it was not until my forced resignation from my first congregation that I truly understood the Book of Job. Without getting into all the details, my elders forced me to resign because they were unwilling to make accommodations for my recent autism diagnosis at the time (particularly understanding my social boundaries), and they despised the last sermon I preached there where I opened up about my mental health struggles in the effort to encourage members of the congregation to seek both professional help and the Word & Sacraments if they’re also suffering with mental health issues.

After the resignation, I spent a lot of time in anger. And even though I truly did nothing wrong to deserve the resignation, like Job, I still justified myself. I could have communicated with the elders better, though neither does my miscommunication justify the elders’ actions. For over a year, I’ve been on CRM status (candidatus reverendi ministerii, candidate for the reverend ministry). During this period of the first circle of hell—Limbo—my suffering has brought me to prayer, repentance, and healing. Through it, I’ve realized my lack of a prayerful life, I’ve had to repent of wrath, and I’ve been receiving healing both through God’s Word and even therapy. And just as Elihu suggested to Job, I have come to see that the Lord has removed me from that congregation to prevent me from falling into further ruin, having saved me from a toxic environment where there is great prejudice against autism and mental health issues.

So, whatever suffering you may be going through, the Lord may also be doing His alien work in you to bring you to His proper work—to bring you back to prayer, repentance, and/or healing. It is the mark of the Christian life: oratio, meditatio, tentatio.

In the Christian life, Luther identified a sacred rhythm of oratio (prayer), meditatio (meditation), and tentatio (trial/affliction) as the true school of theology. Oratio begins with humble prayer, acknowledging our dependence on God for understanding and illumination. Meditatio follows as we dwell on God’s Word—not merely reading it, but internalizing and wrestling with it, letting it shape our minds and hearts. Yet it is in tentatio—the struggles, doubts, and suffering of life—that the Word is truly tested and proven. Affliction drives the truth of Scripture deeper, stripping us of self-reliance and pressing us into the promises of Christ. This cycle is not linear but cyclical and ongoing, drawing the believer repeatedly into deeper communion with God, where theology is not just learned but lived.

A God Who Restores

Returning to Job, Elihu concludes with an appeal to Job: “Behold, God works all these things, twice, in fact, three times with a man, to bring back his soul from the Pit, that he may be enlightened with the light of life” (vv. 29-30). God is not quick to cast off His people. He disciplines in love and often brings us back repeatedly. Elihu is not offering a simplistic formula but a deeper theology of mercy—the sacred rhythm of oratio, meditatio, tentatio. He wants Job to know that even in suffering, God may be working to rescue, not to destroy.

He ends with humility: “If you have anything to say, answer me; speak, for I desire to justify you. If not, listen to me; hold your peace, and I will teach you wisdom” (vv. 32-33). Elihu’s tone is pastoral. He doesn’t want to win an argument. Rather, he wants to see Job restored. And in that longing, Elihu points us toward the Redeemer who disciplines not to crush, but to heal.

Elihu may not speak perfectly (God will also correct him), but his voice introduces something the other friends never did: the possibility that suffering may be redemptive, not merely retributive. His vision of a ransom, a mediator, and a gracious God who rescues the soul from the pit of death is the most gospel-like language we’ve heard so far. In this, Elihu becomes a dim forerunner of the One who will bear our affliction, speak on our behalf, and ransom us by grace alone as our Justifier.

Chapter 33 is a call to reimagine suffering through the lens of mercy. It invites us to listen for God even in the pain, to watch for His hand even in the silence, and to trust that the God who disciplines also delights in us. The pit is not the end of the story. For in Christ, a ransom has indeed been found, and He has descended into the depths to raise you up.