I had always believed that faith was a crutch for the weak, the stupid, and the superstitious—a soft lullaby to hush the unbearable howl of an apathetic universe. My mother used to tell me that God watched over me as I slept, His hand upon my dreams like a gentle moonbeam. But in the raw hours of my youth, when I saw a sparrow twitch and die beneath a neighbor’s cat or when I heard the sobbing of my friend whose little brother was lost to cancer at the mere age of six, I decided that either God was a sadistic puppeteer, or He was nothing at all.

At university, I carried this certainty like a gleaming sword. I read Dawkins and Hitchens, scoffed at the churchgoers, and recited my arguments as if they were holy mantras.

“If God is all-knowing and all-loving,” I’d say, my voice sharp as glass, “then He must be either powerless or cruel, for suffering blooms everywhere like mold on bread.”

My professors nodded. My friends clapped. And I felt the cold triumph of a king ruling over a desolate kingdom of his own intellect.

Then came the hospital room. My father, who’d been as constant and silent as an oak, lay shrunken and pale, his breaths ragged like torn cloth. I watched the monitors flicker like distant stars. No philosopher stood beside me then. No clever phrase could warm the ice that pressed against my ribs.

It was there that I met Sarah—a nurse with a gentle voice and eyes that seemed to echo some ancient kindness.

She prayed aloud one night, her words a trembling candle in the dark. “Lord, hold him when we cannot. Lead him to rest where he cannot stand.”

I wanted to mock her—to spit the old question in her face: “Where is your God now?” Her prayers wouldn’t do anything. Only medicine would! So stop praying and go back to treating my dad!

But the words caught in my throat like a bone. Instead, I watched. I listened. I saw how she washed my father’s face as though she were tending to Jesus Himself, as if she were Mary Magdalene doing for Jesus what she left for the tomb to do. I saw her tears fall, not of defeat but of love so fierce it could only be divine.

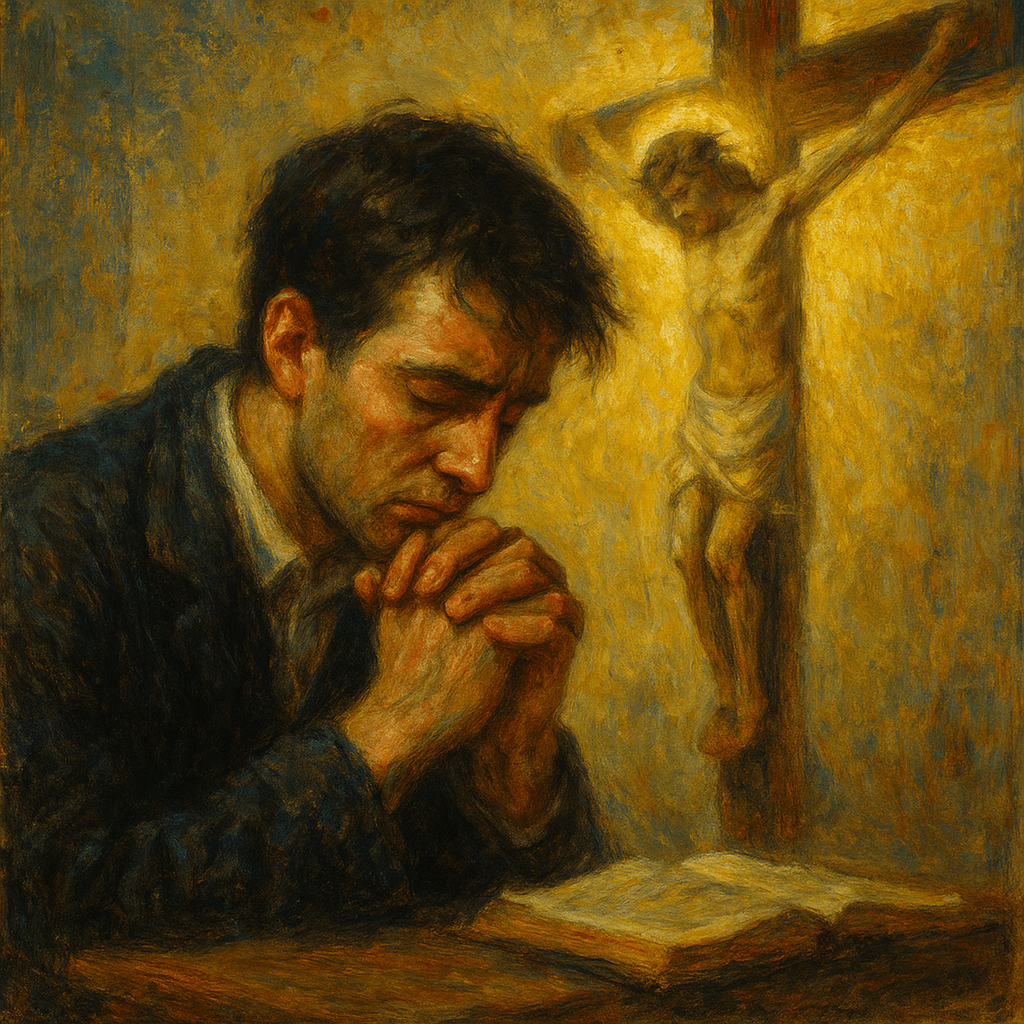

In those weeks, I began to read a Bible she left at my father’s bedside, its pages soft and smelling faintly of lavender. There, I met a God who did not stand far above suffering but plunged headlong into it—a God who wept beside graves, who bled beneath a crown of thorns, who cried out in abandonment so that no soul would be truly alone.

I began to see that love and suffering are not distant strangers but siblings walking hand in hand through the vale of this world. “Why does God allow suffering” is the wrong question. The right question to ask is, “Why would God suffer for us?” And when I asked this, my heart cracked open like a window after a long winter.

My father died with me holding his hand, and Sarah holding his other, whispering psalms that rose like dawn hymns into the sterile room. In that moment, I realized faith is not a crutch but a cross—heavy, splintered, yet carried with a joy that sings beyond the grave.

Years have passed since that day. I no longer wield my sword of skepticism. Instead, I kneel, learning each day that questions are not enemies to faith but companions that teach us to bend low enough to hear God’s whisper.

Sometimes at night, I still hear the old question echo in my mind. But now I answer it with tears, laughter, and a trembling yes; for love—true love—does not flee from pain. It enters it, redeems it, and shapes it into a doorway to eternity.

So when people ask me now, “If God is all-knowing and all-loving, how can there be suffering,” I simply smile and tell them of a God who did not watch from afar but stepped into the muck, the blood, and the dark—to carry us home.