“Can a man be profitable to God, though eh who is wise may be profitable to himself?” — Job 22:2

From Accusation to Allegation

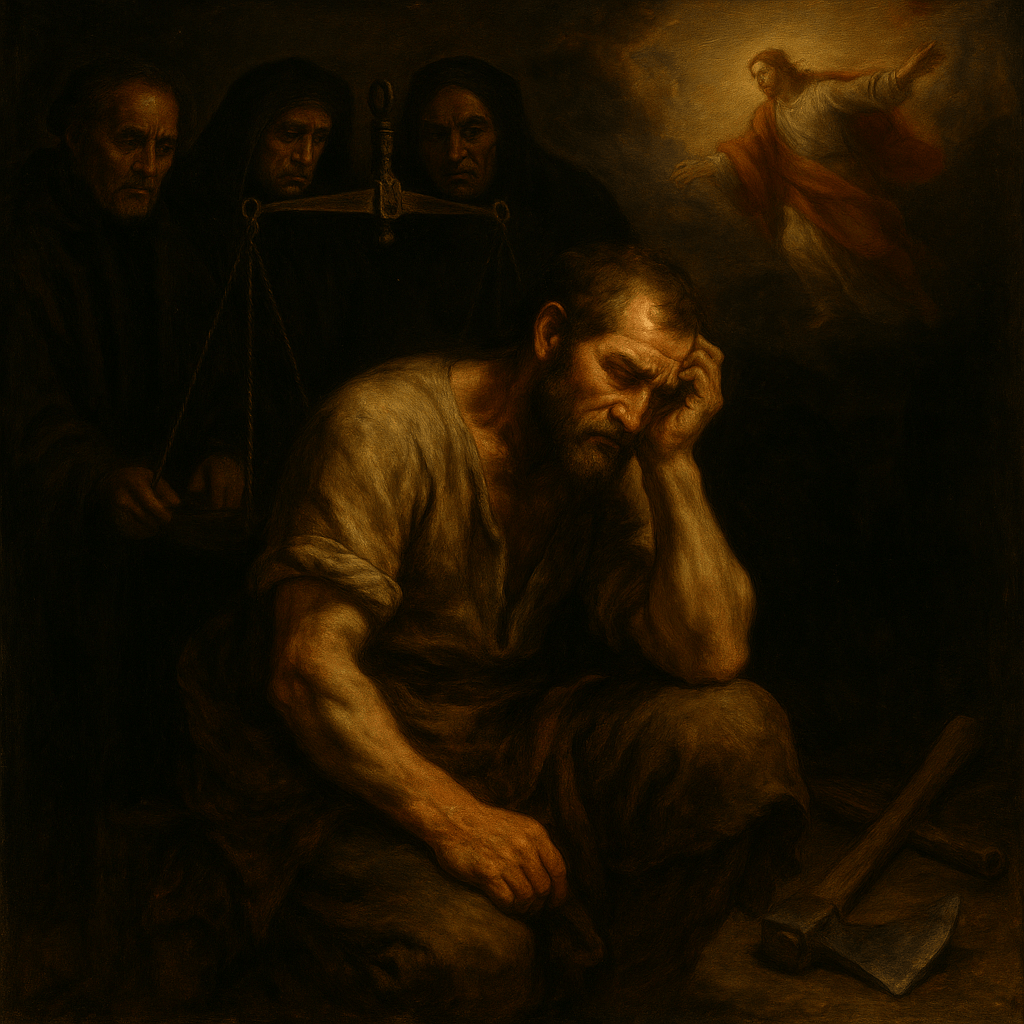

Eliphaz has had enough. In his first speech (Job 4-5), he clothed his accusations in generalities. In his second (Job 15), he relied on visions and tradition. But now, in his final address, he abandons caution entirely and accuses Job directly. “Is not your wickedness great, and your iniquity without end?” (v. 5). He no longer pretends to offer gentle correction. He has pronounced a guilty verdict.

“For you have taken pledges from your brother for no reason and stripped the naked of their clothing. You have not given the weary water to drink, and you have withheld bread from the hungry” (vv. 6-7). These are grave accusations—sins of greed, cruelty, injustice, and neglect. But there’s no evidence for any of it. Eliphaz is not bearing witness; he’s inventing charges to satisfy his theology of glory.

Because Job suffers, Eliphaz must now imagine the sin that explains it. He cannot tolerate the thought that God allows the righteous to suffer. So, he rewrites Job’s life to fit his false doctrine. The comforter thus becomes a slanderer—an 8th Commandment violation. And theology, once meant to proclaim God’s mercy, is now used to inflict wounds that God Himself has not given.

We, too, are tempted to fill in the blanks of others’ suffering when it unsettles our theology. When someone we deem godly suffers without relief, our hearts may look for fault in them—not because it’s true but because it protects our own sense of spiritual control. Eliphaz’s error becomes ours when we assume the role of judge rather than fellow sufferer, when we diagnose without understanding, and accuse without evidence.

On the 8th Commandment (“You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor”), Luther writes, “…this commandment forbids all sins of the tongue [James 3], by which we may injure or confront our neighbor… People are called slanderers who are not content with knowing a thing, but go on to assume jurisdiction… God, therefore, would have such behavior banned, that anyone should speak evil of another person even though that person is guilty, and the latter knows it well, much less if anyone does not know it and has the story only from hearsay. But you say, ‘Shall I not say something if it is the truth?’ …If you do not trust yourself to stand before the proper authorities and to answer well, then hold your tongue. But if you know about it, know it for yourself and not for another. For if you tell the matter to others—although it is true—you will look like a liar, because you cannot prove it. Besides, you are acting like a rascal. We should never deprive anyone of his honor or good name unless it is first taken away from him publicly. ‘False witness,’ then, is everything that cannot be properly proven. No one shall make public or declare for truth what is not obvious by sufficient evidence” (LC I, 263, 267, 269-272).

God does not call us to suspicion—He calls us to compassion. Again, as Luther writes, “…this commandment is given in the first place so that everyone shall help his neighbor to secure his rights and not allow them to be hindered or twisted. But everyone shall promote and strictly maintain these rights, no matter whether he is a judge or witness, and let it apply to whatsoever it will” (LC I, 260). Rather than standing over the wounded in judgement, we are called to kneel beside them in mercy. When we encounter affliction in others, the question should not be, “What did they do wrong,” but “How can I love them as Christ has loved me?” For the true witness of faith is not in offering answers but in bearing burdens, even when we cannot explain them.

A Theology of Utility

Eliphaz begins his speech with a striking question: “Can a man be profitable to God, though he who is wise may be profitable to himself?” (v. 2). At first, it sounds like humility. But beneath the surface is a twisted assumption—that man’s righteousness is irrelevant to God unless it benefits Him. Eliphaz sees piety not as a response to grace but as transaction. If you’re prosperous, it’s because God rewards you. If you suffer, it’s because you’ve failed the exchange somehow.

He adds, “Is it because of your fear of Him that He corrects you, and enters into judgement with you?” (v. 4). This rhetorical question is meant to be dismissive. He’s implying, “Surely, you’re not suffering because you’re righteous—that would be absurd!” In other words, affliction is incompatible with innocence. Once again, Eliphaz has no room for redemptive suffering or undeserved sorrow in his theological framework.

This is the flaw at the heart of the theology of glory: it treats God like a divine employer, not a merciful Father. His God does not weep—He only weighs like a cold judge. He does not comfort—He only calculates like a detached accountant. Such a God might be “fair,” but this is no gracious God.

This theology of utility is not entirely absent in our world. It is especially weaponized against autistic people.[1] For autistic people who do not conform to neurotypical standards of community, productivity, and social performance, this worldview is crushing. Society often treats value as something earned through contribution—your worth is measured by how much you produce, how well you fit in, and how useful you are to the systems around you. But Scripture does not teach this. The God of Job never calls us to prove our worth—He declares it in grace, even before we speak a word.

You are not loved because you’re efficient, articulate, or productive in a capitalistic society. You are loved because you’re made, known, and redeemed. In Christ, God did not choose the strong or socially acceptable; He chose the outcast, the overlooked, and the misunderstood. The world may call some lives less “useful,” but the cross calls them infinitely precious. Eliphaz’s god only rewards performance, but the true God welcomes the weary, the slow to speak, the anxious, and the overwhelmed—and holds them in grace that cannot be earned and will not be taken away.

A Call to Perform

Eliphaz eventually pivots from accusation to prescription: “Now acquaint yourself with Him and be at peace; thereby good will come to you” (v. 21). The logic is simple: confess, repent, and prosperity will return. “If you return to the Almighty, you will be built up; you will remove iniquity far from your tents. Then you will lay your gold in the dust, and the gold of Ophir among the stones of the brooks. Yes, the Almighty will be your gold and your precious silver; for then you will have your delight in the Almighty and lift up your face to God” (vv. 23-26). He describes a spiritual transaction—repentance as investment, and God as the reward.

But Job has already done all this. His life before his suffering was one of integrity, sacrifice, and liturgical intercession (1:1, 4-5). Eliphaz, however, believes Job’s suffering disproves that. Thus, he offers repentance not as grace but as performance. It’s the altar of the false gospel: “Do this, and you will live.” It is the Law disguised as Gospel. It turns God’s favor into a wage and man’s worth into a test.

This is not merely poor advice—it’s pastoral malpractice. For those who suffer unjustly, this kind of theology deepens despair. It tells them that if pain remains, it’s because they’re insufficient. It makes healing conditional, mercy transactional, and God’s love dependent on results. In short, it offers a religion of self-effort rather than divine compassion.

You may know this burden all too well—the pressure to perform in order to be loved, accepted, or counted, whether it came from your parents, your job, or even your church. For those with disabilities, chronic illness, or mental health struggles, it can feel as if worthiness must constantly be earned. Society, and too often the Church, treats visible weakness as a spiritual problem to be solved rather than a cross to be borne with dignity and a Simon of Cyrene to help bear it for a while. But Eliphaz is wrong: God does not wait to bless you until you’re fixed. His love comes first.

God’s grace does not begin at the finish line of personal improvement. It meets us where we are—wounded, confused, and tired of trying to prove ourselves. Christ does not say, “Perform, and I will save you,” but “Come to Me, all you who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take My yoke upon you and learn from Me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For My yoke is easy and My burden is light” (Matthew 11:28-30). The Gospel is not a transaction—it’s a gift with no strings attached. And in the face of every voice—internal or external—that says, “You must do more,” the cross declares, “It is finished.”

When Mercy is Missing

Eliphaz’s closing words are meant to inspire confidence: “You will make your prayer to Him, He will hear you, and you will pay your vows… He will even deliver one who is not innocent; yes, he will be delivered by the purity of your hands” (vv. 27, 30). But even these words are poisoned by performance—by Eliphaz’s works-righteousness theology. They imply mercy is available, but only through the hands of the righteous—and only after judgement has been satisfied.

There is no cross in this vision, no Mediator who pleads for the ungodly, no Redeemer who intercedes for sinners while they’re still in the pit of despair. Eliphaz’s god helps—but only after you’ve earned it. He forgives—but only once your repentance is spotless. He restores—but only when your record is clean.

This is not the God Job hopes in. It is not the God who justifies the ungodly (Romans 4:5). It is not the Father who runs to the prodigal son, or the Christ who cries, “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they do” (Luke 23:34). Eliphaz cannot imagine a God who blesses the unworthy, so he must insist Job is cursed because he deserves to be. But Job refuses that story. He’s waiting for a different Word.

You might live under the weight of this same lie—that God is kind only to the strong, merciful only to the morally polished, and present only after improvement. When the Church forgets mercy and emphasizes merit, it leaves the weary with nowhere to go. Those already crushed by grief or guilt are told to rise first, then they may approach the altar. But the God who comes to Job—the God who comes to us in Christ—does not wait at a distance. He enters the ashes first.

To the broken, the exhausted, the ones who feel far too gone—you are not asked to bring clean hands. You are simply invited to the feast (Matthew 22:1-14). You are not delivered by the purity of your own record but by the pierced hands of Another. Mercy is not the reward of performance—it is the heartbeat of God. And it is yours, not when you rise to Him, but when He stoops down to you in Divine Service.

A Theology that Accuses or Redeems

Eliphaz has finally shown his hand. He believes in a God who is efficient, predictable, and transactional. Thus, when faced with suffering he cannot explain, he rewrites reality to protect his theology of glory. In doing so, he accuses the innocent and comforts no one. He offers correction where compassion is needed, and formulas where only faith can survive. But Job’s Redeemer is not like Eliphaz’s god. The God Job longs for is not useful—He is gracious. He does not require perfection to hear prayer, nor demand purity before He saves. He put on our flesh. He answers from the whirlwind (38:1). And he reveals love is not earned but given. Job will not find this Gospel in the mouth of his friends, but it will soon thunder from the mouth of God.

[1] Note to reader: I’ve received a late diagnosis of “level 1” Autism Spectrum Disorder.