“Where then is my hope? As for my hope, who can see it? Will they go down to the gates of Sheol? Shall we have rest together in the dust?” — Job 17:15-16

The Eyes of the Broken

Job 17 opens not with resignation instead of a complaint: “My spirit is broken, my days are extinguished, the grave is ready for me” (v. 1). Job no longer pleads for restoration—he prepares for death. His body is failing, his soul is crushed, and the future offers no visible relief. The flickers of hope from chapter 16—his cry of a heavenly witness—have dimmed under the relentless silence of Heaven and the betrayal of his companions. Little does he know that God commanded Satan not to take his life (2:6).

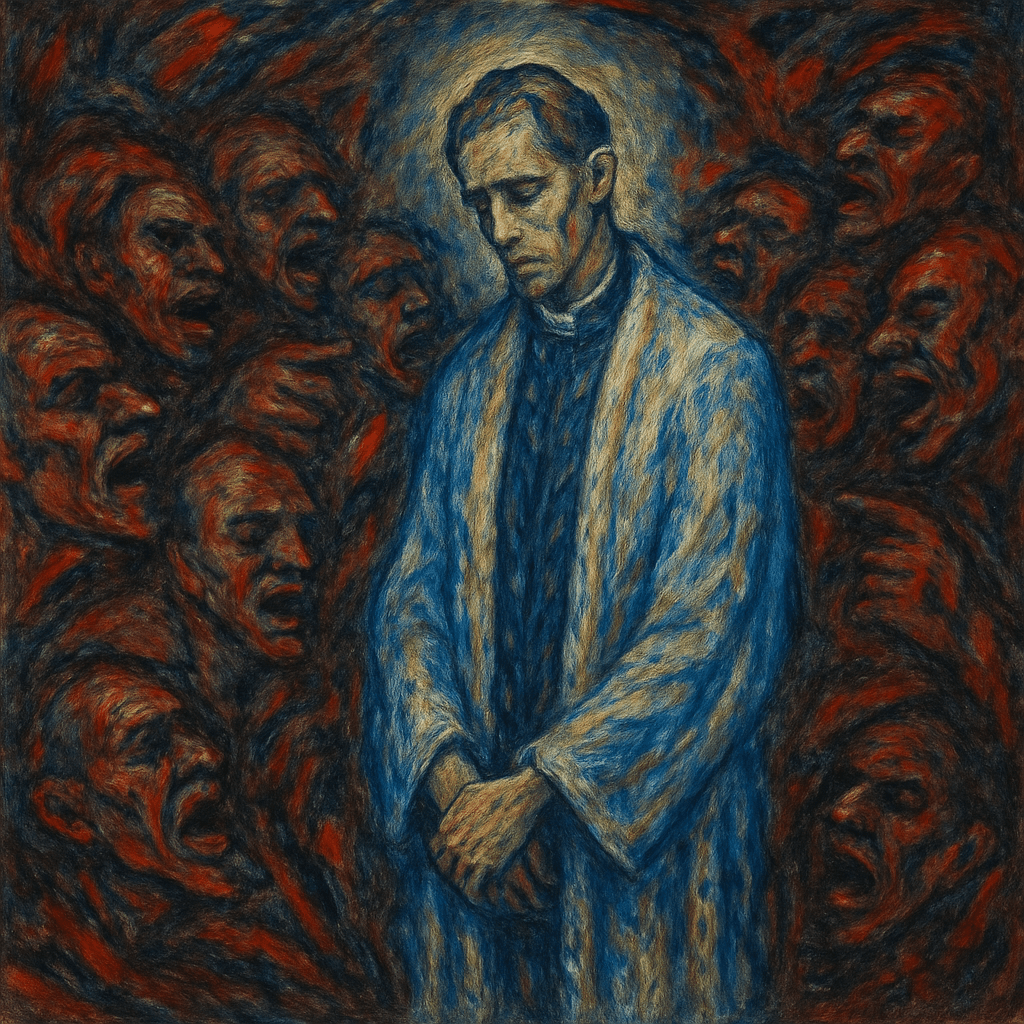

“Are not mockers with me? And does not my eye dwell on their provocation?” (17:2). Job’s grief is compounded by human cruelty. The eyes that once looked with trust now see only scorn. He’s alone, encircled by those who misunderstand him, dismiss his pain, and weaponize theology against his soul. When suffering isolates a person from their community, the weight of that grief doubles, and Job feels every ounce of it.

These are the eyes of one who’s seen too much sorrow and too little mercy. Job no longer looks outward in hope but inward in grief. His perception is colored by pain, his gaze fixed on those who wound instead of those who might help. When the soul is raw, even the glance of others can feel like a blow. His complaint is not that they’ve failed to fix his suffering; it’s that they’ve deepened it through their cruel words.

And yet, there is faith even in these words. Job does not numb himself or retreat into false hope; he sees the truth of his situation and still speaks. The eyes of the broken are not blind—they are painfully sharp. And what Job sees, though devastating, is spoken aloud in the presence of God. In that, he teaches us there is dignity in naming despair, and that even eyes full of tears can still be eyes of faith, though they be blurry.

A Plea for the Grave

In verse 3, Job does something remarkable. Even in despair, he addresses God directly: “Now put down a pledge for me with Yourself. Who is he who will shake hands with me?” He’s asking for a bond—a guarantee, a divine surety. In the ancient world, a pledge was a formal agreement—a promise backed by collateral. Job pleads for God to make a covenant with him since no man will stand with him. He no longer trusts the justice of this world, so he asks for the justice of the world to come.

But even that prayer trembles on the edge of silence. “But He has made me a byword of the people, and I have become one in whose face men spit” (v. 6). He’s not merely ridiculed—he is dehumanized. Job’s name, once honored in the gates, is now a proverb of shame. His body is sick, his mind tormented, and his dignity shattered. “My eye has also grown dim because of sorrow, and all my members are like shadows” (v. 7). This is the language of a man already fading, one who’s beginning to mourn himself before he has died. Again, he expresses second-hand suicide.

I used this term back in chapter three. Like Job, this is something I have much experience with in my own clinical depression. Second-hand suicide is the deeply painful desire to die without the will or intent to actively take one’s own life. It’s not about planning or executing that end, but about longing for life to simply cease—for death to finally take you. Those experiencing it often wish they could fall asleep and never wake up, or hope for some external force—an illness, an accident, or just the quiet erosion of being—to erase them from existence. It arises not from a dramatic urge but from a wearied despair, often invisible to others, rooted in the belief that one’s absence would bring peace rather than pain. This form of suicidal ideation is insidious because it can persist silently, masked by outward functioning, yet it reflects a profound detachment from the will to live.

When the Righteous Are Despised

Job’s next words are a bitter indictment of a world turned upside down: “Upright men are astonished at this, and the innocent stirs himself up against the hypocrite” (v. 8). He sees his suffering not as an isolated event but as a cosmic scandal. The innocent suffer. The righteous are ridiculed. The world looks on and does nothing. For Job, this is not just personal pain—it’s a theological crisis. If the upright are mocked and the wicked prosper, what has become of God’s justice?

Yet he adds, “Yet the righteous will hold to his way, and he who has clean hands will be stronger and stronger” (v. 9). This is not triumphalism but bold defiance. Job affirms true righteousness is not situational—it endures even when misunderstood. In this confession, Job shows faith is not destroyed by suffering. It may be disoriented, but it persists. The righteous cling to their integrity because it reflects the God they trust, not because it benefits them.

This is the kind of confession that unsettles the false comforters. Job will not surrender his integrity to satisfy his friends’ bad theology. Even though it seems God has hidden His face, Job refuses to become what they accuse him of being. The righteous man, even when despised, does not abandon righteousness. His faith may tremble, but it does not break, for it is sustained by the gifter, not the receiver. And in this, Job becomes a prophetic figure of perseverance. “And not only that, but we also glory in tribulations, knowing that tribulation produces perseverance; and perseverance, character; and character, hope. Now hope does not disappoint, because the love of God has been poured out in our hearts by the Holy Spirit who was given to us” (Romans 5:3-5). (See this article on these verses.)

Such perseverance prefigures the cross. Christ, the Righteous One, was mocked, misunderstood, and condemned—yet He held to His Way, committed no sin, and entrusted Himself to the Father (1 Peter 2:23-24). In Job, we see the shape of this righteousness in shadow; in Christ, we see it fulfilled in flesh. The world may despise the righteous, but Heaven never forgets them. Job’s endurance bears witness to a greater Redeemer whose vindication would rise from a tomb, not just from an ash heap.

A House in the Darkness

But even that brief surge of strength is fleeting. Job turns again to his so-called friends: “But please, come back again, all of you, for I shall not find one wise man among you” (v. 10). He invites them to speak again, not out of hope but as a dark taunt. He has exhausted their counsel. He no longer expects wisdom from them. He expects more of the same: hollow accusations and shallow theology.

“My days are past, my purposes are broken off, even the thoughts of my heart” (v. 11). This is grief beyond the physical. Job mourns the loss of meaning, the collapse of vocation, and the unraveling of hope. His future is gone. His desires are meaningless. The thoughts that once sustained him have become unbearable.

Once again expressing the phenomenon of second-hand suicide, he describes death as his only resting place: “They change the night into day; ‘the light is near,’ they say, in the face of darkness. If I wait for the grave as my house, if I make my bed in the darkness… where then is my hope? As for my hope, who can see it?” (vv. 12-13, 15). The voices around him keep insisting light is near, but Job knows they’re “lying.” He no longer believes in quick restorations. His only house is Sheol, his only peace the dust.

With this second-hand suicide, Job is not planning his death, but he is pleading for it. He does not wield the knife; he simply wearies of fighting—of white-knuckling through life. This is a deep pit of despair, and it is tragically common among the suffering who feel forgotten both by man and God. It does not come from hatred of life, per se, but from weariness of unresolved pain.

And yet, even in that dark longing, Job speaks to God. He does not pray in joy, but he prays, nonetheless. His hope is not extinguished—it is buried, waiting for resurrection. For every soul who has ever whispered, “I just wish I were dead,” Job offers a strange kind of comfort: that even such prayers can be part of faith. And the God who heard Job’s cry in the dust is the same God who, in Christ, descended into it—to bring hope not only to the dying but also to the ones who wish they were dead.

Hope Buried, But Not Lost

Job 17 ends not with a resolution, but a question: “Where then is my hope?” (v. 15). It’s not rhetorical—it’s sincere. Job is asking what every sufferer asks when prayers go unanswered, and pain has no satisfying explanation. He’s not demanding an answer; he’s naming the silence.

And yet, in naming that silence, Job shows us the anatomy of true faith: he speaks to God even when he no longer feels Him. He continues the conversation even when all evidence suggests God has withdrawn. This is not a loss of faith—it is its deepest form. Job’s hope may be buried, but it is not lost. It lies dormant, like a seed in winter, waiting for the warmth of the Sun of Righteousness (Malachi 4:2).