“Should a wise man answer with empty knowledge and fill himself with the east wind?” — Job 15:2

The Shift from Counsel to Condemnation

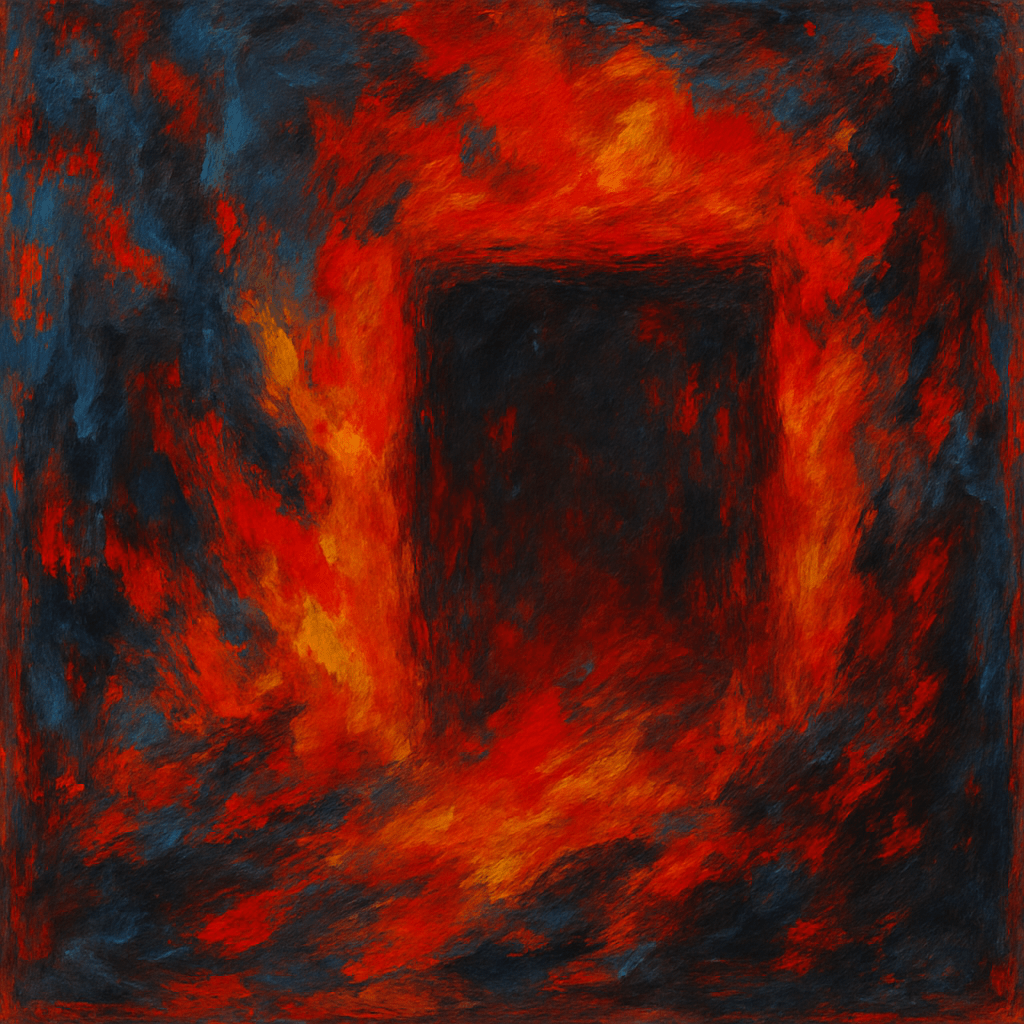

In Eliphaz’s second speech, his tone turns sour. Gone is the cautious mysticism of his earlier words in chapter 4, where he spoke of visions and whispers in the night. Now, his speech is barbed with frustration and full of accusation: “Should a wise man answer with empty knowledge and fill himself with the east wind?” (v. 2). The east wind, in biblical imagery, is harsh, dry, and destructive. Eliphaz compares Job’s lament to this—feckless, dangerous bluster.

Eliphaz can no longer tolerate Job’s honest wrestling. He views it as rebellion masked as piety. In his eyes, Job’s words are not the cries of the wounded but the rants of the wicked: “Yes, you cast off fear and restrain prayer before God” (v. 4). Clearly, Eliphaz hasn’t been paying attention, for Job has been praying before God this entire time! He interprets Job’s pain as spiritual arrogance. Because Job refuses to confess a sin he has not committed, Eliphaz assumes Job has lost all reverence for God.

This marks a theological failure of immense gravity. Eliphaz cannot conceive of a righteousness that suffers. In his framework, silence from God proves guilt. Pain means punishment. Lament means rebellion. Thus, he condemns Job for having the audacity to cry aloud and to believe his suffering might be unjust.

In verses 5-6, Eliphaz escalates the attack: “For your iniquity teaches your mouth, and you choose the tongue of the crafty. Your own mouth condemns you, and not I; yes, your own lips testify against you.” His words are merciless. It’s not Eliphaz who’s condemning him, but Job’s own words! He believes Job’s very speech is sinful—that the content of his lament exposes a corrupt heart. This is not just bad theology; it is pastoral cruelty. Eliphaz mistakes pain for pride and turns piety into prosecution.

He continues, “Are you the first man who was born? Or were you made before the hills?” (v. 7). Eliphaz sarcastically mocks Job’s search for answers by accusing him of pretending to have divine wisdom. His sarcasm drips with scorn. He cannot hear the humility in Job’s cries because he’s too offended by the fact that Job speaks at all.

In Eliphaz, tradition is truth. He appeals to the wisdom of the elders, the sayings of the sagacious, and the experience of past generations (vv. 9-10, 17-18). He believes Job is arrogant simply for questioning the received order. But this is the blindness of the theologian of glory: assuming that what has always been said is always right, regardless of the present suffering before one’s eyes. Eliphaz’s theology is static, cold, and utterly unable to bend beneath the weight of real grief.

Eliphaz offers a vision of God that is terrifying. He describes the fate of the wicked in vivid, punishing detail: “The wicked man writhes with pain all his days, and the number of years is hidden from the oppressor… He does not believe that he will return from darkness, for a sword is waiting for him… Trouble and anguish make him afraid; they overpower him, like a king ready for battle” (vv. 20, 22, 24). There’s some truth in these words—Scripture does warn of judgement for the wicked—but Eliphaz, just like Bildad and Zophar, misapplies them with reckless confidence.

He sees Job’s suffering and assumes it must mirror these curses. His logic is a simple syllogism: Job suffers, the wicked suffer, therefore Job is wicked. But this is a grotesque misuse of God’s justice. It turns divine judgement into a weapon of suspicion. It proclaims Law without promise and wrath without mercy—a confusion of Law & Gospel.

There’s no grace in Eliphaz’s theology—no room for the righteous sufferer, no category for affliction that purifies rather than punishes. His words describe a world where God’s favor is always visible, and His judgement always immediate. But that is not the world of the cross. That is not the world of Christ, who was Himself “a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief” (Isaiah 53:3)—and yet without sin.

The Emptiness of Confident Error

Eliphaz’s speech is saturated with certainty in his prosperity gospel. He quotes the wisdom of elders, recites the fate of the wicked, and applies both to Job’s situation without hesitation and wise discernment. But this certainty is not the fruit of faith—it’s the dagger of fear. Eliphaz cannot endure the mystery of innocent suffering, so he explains it away. He cannot sit in silence with Job, so he speaks with force. He cannot pray, so he prosecutes.

This is a warning for pastors and Christians alike: the temptation to speak where God has not spoken, to declare what God has not declared, and to comfort ourselves by condemning others. Eliphaz speaks not to comfort Job but to protect his own theology that cannot properly deal with Job’s suffering. He cannot believe Job is a righteous sufferer, because then he might have to admit righteousness does not promise freedom from suffering. Job’s predicament has produced a cognitive dissonance in his mind. If he heard the Savior’s words, “In the world you will have tribulation” (John 16:33), he would perhaps become apoplectic.

Eliphaz accuses Job of filling the air with wind—but it’s his own words that prove hollow. His speech, though full of religious language, carries no mercy, no Gospel, and no invitation to hope. He has defended God in his theodicy at the expense of truth and wounded a righteous man in the name of orthodoxy.

What Job needs is not a fire-and-brimstone sermon but a friend who believes in a God who listens. What Job longs for is not a doctrine of immediate reward and punishment but a Mediator who will vindicate him at the last. Eliphaz offers neither. Thus, his words become a caution: when theology forgets compassion, it ceases to be true—even if every syllable sounds biblical.

The wise man does not fear empty knowledge; the wise man fears speaking falsely for God. And in that reverent fear, he learns to be silent, to listen, and to wait with the one who suffers—until God Himself breaks the silence.