In an age saturated with therapeutic advice and psychological slogans, many Christians have unwittingly baptized the self-help movement into their spiritual lives. Walk into a Christian bookstore or browse popular devotional blogs, and you will often find the same mantra repeated in various forms: Believe in yourself. Trust in your journey. Speak your truth. Heal your inner child. Or as Paula White likes to tweet, “God is opening doors and shifting your season.” These are modern psalms of our culture—lyrics meant to soothe the soul. But their melody is both shallow and hollow, and their rhythm leads us not toward peace but deeper into our sinful nature.

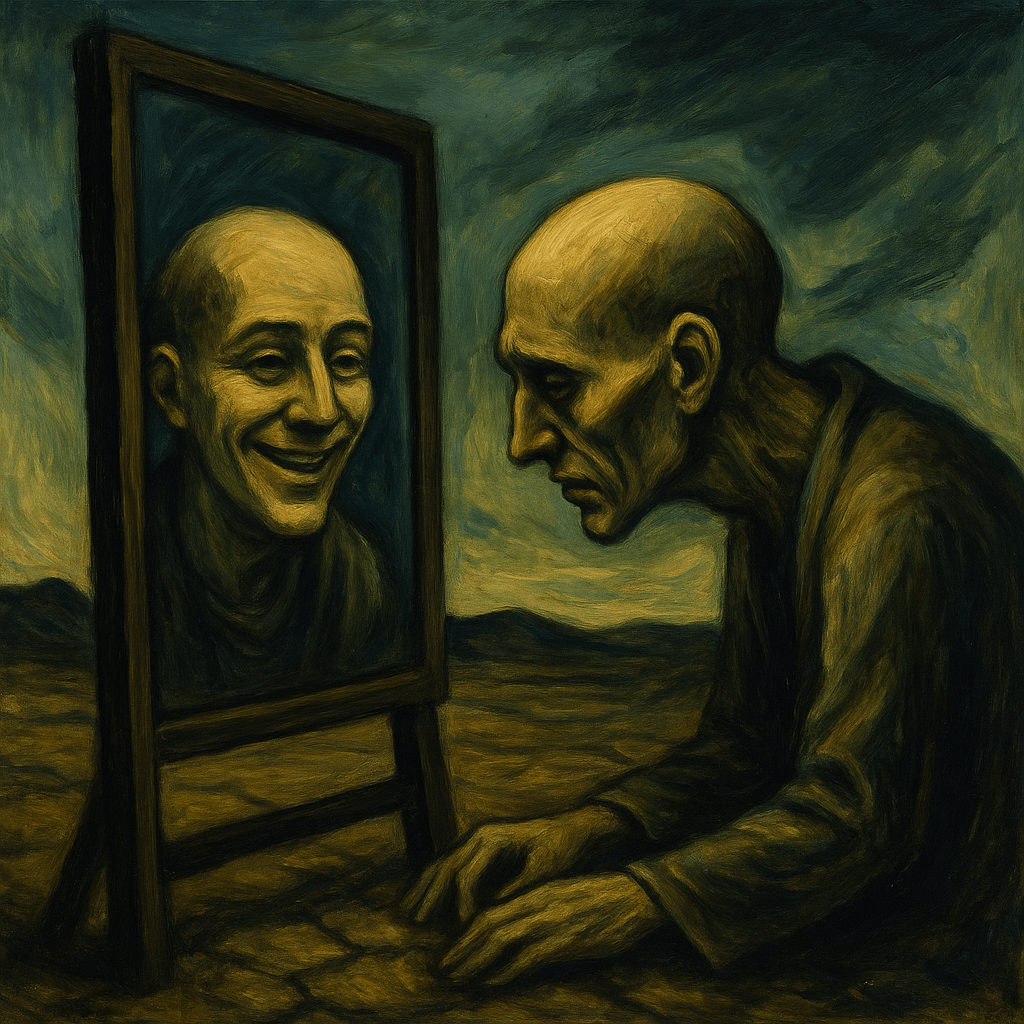

Such messages pose both a theological and spiritual danger. They subtly replace the cross of Christ with the mirror of the self—the ego. Instead of clinging to Christ crucified and risen, we are encouraged to cling to our own resilience. Instead of confessing our sins, we’re taught to affirm our worth (not that we don’t have intrinsic work as bearers of God’s image). Instead of listening to the Word, we’re told to listen to our hearts. But “the heart is deceitful above all things and desperately wicked” (Jeremiah 17:9). What the world calls healing, Scripture often identifies as delusion.

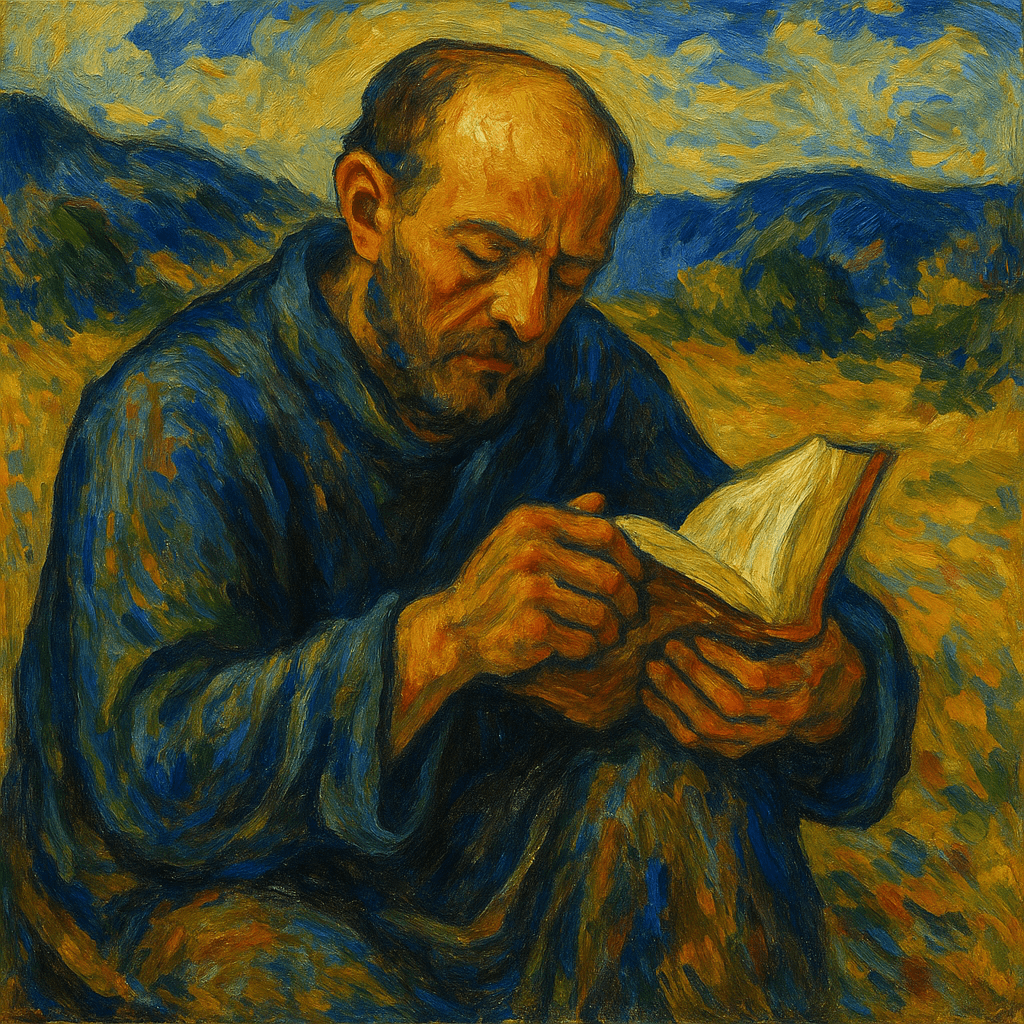

Psalm 119:25-32 offers us a better way—a sacred counter-testimony to the cult of self-help. It does not tell us to fix ourselves but to be raised by the Word. It does not encourage self-discovery but divine instruction. It does not glorify personal strength but confesses human frailty and cries out for God’s reviving grace. This section of the acrostic poem speaks honestly of sorrow, confusion, weakness, and shame—but it also speaks of the God who hears, answers, strengthens, and enlarges the heart.

In what follows, we’ll walk through each verse of Psalm 119:15-32, confronting the self-help narrative at every turn with the life-giving truths of Scripture. As we go through it, remember that the Law reveals our helplessness and the Gospel declares our hope. Let us now listen to this ancient Word—not to find power within ourselves but to be drawn again to the Christ who is our only help, our only truth, and our only life.

The Dust of the Self (v. 25)

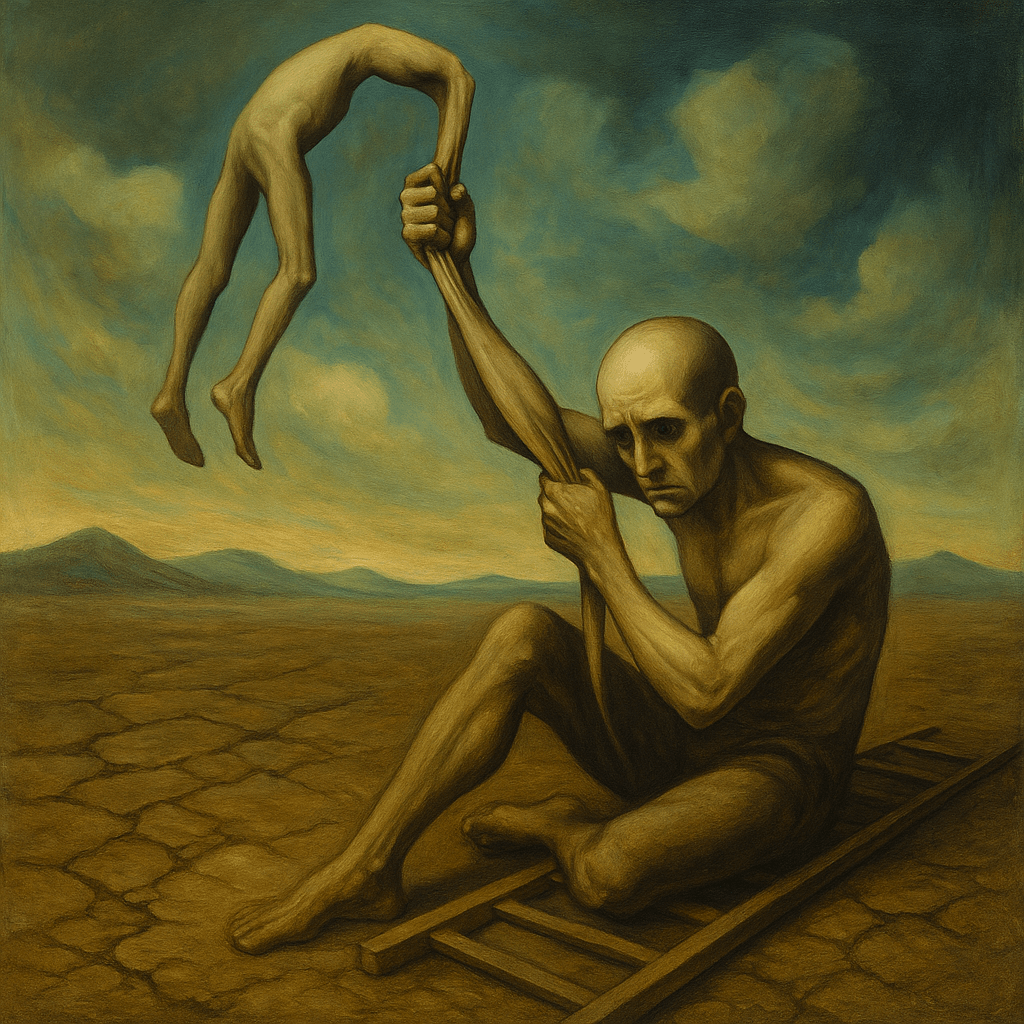

“My soul clings to the dust; revive me according to Your Word.” The psalmist opens with a stunningly vulnerable admission: his soul is not merely struggling—it is cleaving to the dust. This is a confession of despair and lifelessness. The Hebrew word for “cling,” דוק (davaq), denotes a deep, inseparable attachment. The same verb is used elsewhere for marital union or for clinging to God. Here, however, it’s twisted into a grotesque parody—the soul clings not to the Lord but to the lowliest, most lifeless matter: dust. This is a biblical way of saying, “I’m at my wit’s end.”

This is the point where self-help psychology falters most. It assumes people have the intrinsic capacity to rise from this state. But Scripture is clear: we are dust, and to dust we shall return (Genesis 3:19). The soul in this condition cannot manufacture life. Encouraging someone to look within themselves for the strength to rise is like telling a corpse to perform CPR on itself. Theologically, this is why we confess original sin—not merely as inherited guilt but as total spiritual incapacity apart from divine intervention.

What is needed is not self-guided therapy for the flesh but resurrection by the Word. That is the cry of the psalmist: “Revive me according to Your Word.” The Word of God is not merely informative; it is performative. It’s efficacious—it does what it says (Isaiah 55:10-11). Just as God spoke light into darkness and life into Adam’s dust, so the psalmist pleads for that same enlivening Word to act upon him. The Gospel does not give the sinner a second chance—it gives the sinner new life. It doesn’t motivate; it resurrects.

When the self-help movement tells us we need to believe in ourselves, it ironically condemns us to the very dust the psalmist is stuck in. Believing in oneself while lying in the dust is like asking a drowning man to pull himself out by his own hair. It only tightens the noose of self-reliance. But the Word of God meets us in that dust. Jesus Christ became dust for us. He entered death, became sin (2 Corinthians 5:21), and was buried in our grave so that when He speaks, we who cling to the dust may cling to Him, the living God, instead.

The Answer is Not Within (vv. 26-27)

“I have declared my ways, and You answered me; teach me Your statutes.” The psalmist’s next move is to declare his ways before God. This act of confession is not therapeutic self-narration, as pop psychology suggests, but an act of faith. He’s not “finding himself” by venting into the void; he’s seeking the Lord who hears and answers. When he says, “You answered me,” it reveals the dialogical nature of faith—interaction, not introspection. The Christian life is not a monologue but a continual prayer-conversation with the God who speaks in His Word.

Self-help books are filled with language about finding your “true self” through journaling, vision-boarding, or repeating affirmations. Practically speaking, these practices can be helpful for self-reflection and growth, but ultimately they’re insufficient. Scripture teaches the self is not the source of truth but often the source of deception (Jeremiah 17:9). Declaring “my ways” apart from God is simply airing grievances or seeking validation. But declaring one’s ways to God is repentance. It is exposing our fractured selves to the healing light of the Word, not just naming wounds but submitting them to the Great Physician.

Notice the psalmist is not content just to speak. He also says, “Teach me Your statutes.” He desires to learn. This is the cry of a soul that no longer wants to manage its own narrative but to be formed by God’s story. Self-help places the burden of authorship on the individual. Christianity places it in God’s hands. The psalmist no longer wants to direct his path; he wants to walk according to the Creator’s design. This is the death of autonomy and the birth of holy dependence.

In the Divine Service, this moment is echoed when we confess our sins and hear the Absolution. We declare our ways so the Lord might answer us with the forgiveness of sins, not to empower ourselves. “As far as the east is from the west, so far has He removed our transgressions from us” (Psalm 103:12). In a world addicted to affirmation, the Church offers something far better: absolution. Absolution is not a pat on the back; it’s the Word of God that declares, “I forgive you all your sins. You are clean.”

Self-help psychology emphasizes what Luther sharply criticized as enthusiasm (from the Greek enthousiasmos, meaning “having God within”), which he defined not as spiritual zeal but as a dangerous theological error. He writes:

God grants His Spirit or grace to no one except through or with the preceding outward Word [Galatians 3:2, 5]. This protects us from the enthusiasts (i.e., souls who boast that they have the Spirit without and before the Word)… All this is the old devil and old serpent [Revelation 12:9], who also turned Adam and Eve into enthusiasts. He led them away from God’s outward Word to spiritualizing and self-pride [Genesis 3:2-5]… In the same way, our enthusiasts today condemn the outward Word… They fill the world with their babbling and writings, as if the Spirit could not come through the apostles’ writings and spoken Word, but has to come through their writings and words.

SA III, VIII, 3, 5-6

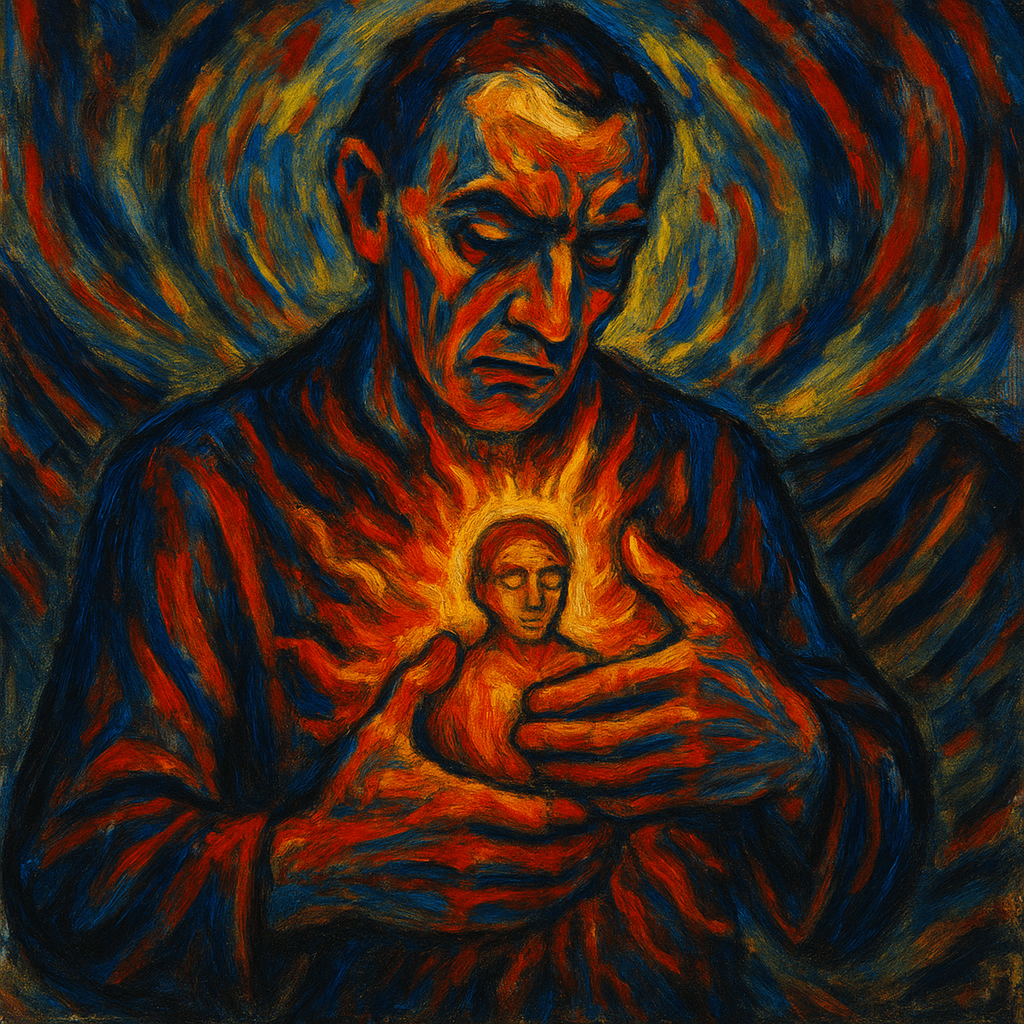

This “God-withinism” seeks divine truth through internal expressions, feelings, or mystical experiences, bypassing the external, preached Word and Sacraments. For Luther, this inward turn is the birthplace of every heresy, as it places personal experience and emotion above the external means through which God has actually promised to work. When a person seeks God in themselves, they end up finding only themselves—and mistaking it for God.

Against this error, Luther upheld what we call extra nos (outside us)—that our righteousness, comfort, and assurance come not from within but outside us. The Gospel is not found in our emotions, our thoughts, or our progress in sanctification. It is found in the external Word proclaimed to sinners and in the corporeal Sacraments administered to those in need. Christ is not discovered in the hidden depths of the soul but revealed in the concrete promises of Baptism, Absolution, and the Lord’s Supper. As Luther wrote in The Freedom of the Christian:

When, I say, such a person shares in common and, indeed, takes as his own the sins, death, and hell of the bride [the Church] on account of the wedding ring of faith, and when [Christ the Bridegroom] regards them as if they were His own and as if He Himself had sinned—suffering, dying, and descending into hell—then, as He conquers them all and as sin, death, and hell cannot devour Him, they are devoured by Him in an astounding duel. For His righteousness is superior to all sins, His life more powerful than death, and His salvation more invincible than hell.

Wengert, 500-501

Faith grasps Christ as a ring grasps a jewel. The value is not in the faith itself but in the object it clings to. This is the foundation of true Christian comfort: I do not look to myself, but to Christ. In a world that constantly urges us to look within for assurance, the doctrine of extra nos lifts our eyes to the cross where Christ has done all things for us. This is further emphasized in verse 27, “Make me understand the way of Your precepts; so shall I meditate on Your wonderful works.” The psalmist looks to the external Word and works of God, not to his feelings that already damned him in verse 25. And this is further emphasized in the following verse.

The Weight of the World (v. 28)

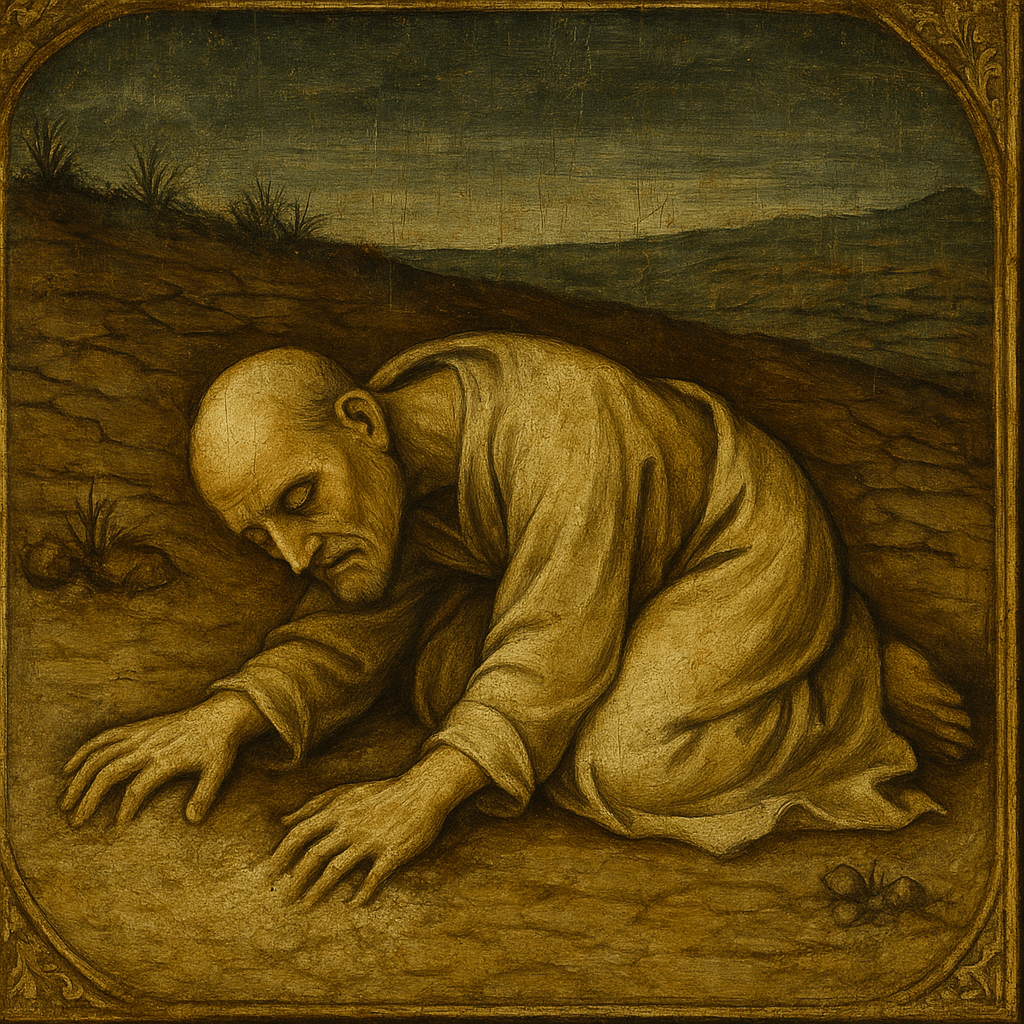

“My soul melts from heaviness; strengthen me according to Your Word.” The soul, once clinging to the ground, now dissolves under emotional weight. This is not merely poetic flourish; it’s the honest admission of someone being crushed by grief, guilt, or exhaustion. And in this moment, self-help is exposed for what it is: a fragile raft in a storm. It cannot bear real sorrow; it can only suggest distractions or reframe the problem. Yet sorrow remains and heaviness still clings.

Modern psychology may offer helpful diagnostic categories—depression, anxiety, trauma—and I myself have benefited from therapy and even medication. Therapy can be extremely useful, even for Christians. While therapy can help one break negative habits of thinking and behavior, it cannot give absolution. Therapy, therefore, is not an end in itself (it’s always the therapist’s goal to no longer have you as her client!). Its solutions are ultimately limited, especially when God’s Word is absent; and pop psychology is even worse because it oversimplifies complex human struggles into catchy slogans and shallow advice, offering illusion instead of insight and wisdom that fears the Lord (see Proverbs 9:10). As useful as they are, behavioral techniques, mindfulness exercises, and affirmations are extremely limited. What they lack is atonement. They name the burden but cannot remove it. Only the cross can do that. The psalmist does not ask for a technique or a unique breathing exercise. He asks for strength. And not just any strength—strength that comes from God’s Word.

The Word of God is where real help is found, to which the Holy Spirit—the Paraclete (the Helper)—guides us. This is why Christians must be wary of replacing the public preaching of Law and Gospel with therapeutic moralism. In many churches, sermons have become self-help lectures with a thin Christian veneer, hardly distinguishable from a TED Talk or a speech from a motivational speaker. The psalmist points us to the opposite direction: the Word is not something we use to feel better; it’s the living voice of the crucified and risen Christ, whose power is made perfect in weakness (2 Corinthians 12:9). His Word strengthens because it speaks with the authority of the One who bore our burdens on Golgotha.

Instead of temporary relief, the Church offers eternal truth. The soul melting from heaviness needs more than a motivational speech or a bumper sticker theology. It needs the God who sweat drops of blood, who wept at Lazarus’ tomb, and who speaks comfort that endures. “Come to Me,” He says, “all you who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take My yoke upon you and learn from Me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For My yoke is easy and My burden is light” (Matthew 11:28-30). The psalmist does not ask to be made strong for his own sake; he asks to be made strong by the Word that bears him up.

Self-Deception and Divine Illumination (v. 29)

“Remove from me the way of lying, and grant me Your Law graciously.” Now the psalmist turns to the problem of deception—not only lying to others but the more insidious self-deception that self-help encourages. The “way of lying” includes falsehoods we live by: “I’m okay.” “I don’t need help.” “If I just try harder, I can fix myself.” “I’m spiritual, not religious.” “God helps those who help themselves.” These are the silent creeds of modern culture. And the more we repeat them, the further we drift from the truth that sets us free, which is the external Word of Christ (John 8:31-32).

The psalmist knows he’s prone to wander. So, he doesn’t ask for better self-awareness or stronger willpower—he asks God to remove the lie. This is the cry of someone who knows the darkness is not just outside him but within. Self-help insists we create our own truth, but the psalmist begs God to destroy his lies and give him the Law graciously. That may sound contradictory—how is the Law gracious? It’s gracious because it reveals our need for the Savior and therefore leads us to the Gospel where we receive Him. It crushes the ego so that Christ can raise the self in Him.

There’s no greater act of divine mercy than to expose our delusions and lead us into truth. This truth, as noted above, is not an idea but a Person. Christ is the way, the truth, and the life (John 14:6). The psalmist longs not for a more positive self-image or self-esteem but for a true vision of God’s will. And he calls it a gift: “Grant me Your Law graciously.” This is repentance in its purest form.

Luther put it well in his explanation to the 1st Commandment in the Small Catechism: “We should fear, love, and trust in God above all things.” Self-help often ends in trusting ourselves above God. But that’s the way of lying—of self-deception. It may soothe for a moment, but it kills in the end. Better to be cut by the truth than coddled by a lie. The psalmist wants no more lies; he wants the truth, even if it wounds like a surgeon’s scalpel, for only then can he begin to heal.

Choosing the Truth Beyond the Self (v. 30)

“I have chosen the way of truth; Your judgements I have laid before me.” With the lying ways behind him, the psalmist proclaims his allegiance to “the way of truth.” This choice is not a shallow preference or emotional inclination; it’s a decisive rejection of self-deception and a turning toward God’s revealed will. In a world awash with relativism and personal truth, the psalmist anchors himself in something objective, immutable, and divine: “Your judgements I have laid before me.” The image is almost judicial—a courtroom where the psalmist submits himself not as judge but as one judged by God’s Word.

Self-help teaches truth is what works for you, what helps you feel fulfilled, or what makes sense in your journey. But the psalm leads us to submit to the objective truth of God’s Word, not to subjective impressions. The psalmist confesses here the norma normans—the norming norm, also known as Scripture alone (sola Scriptura), the ultimate standard by which all other standards are judged. The psalmist doesn’t consult his feelings or experiences to find the way; he lays out the Lord’s judgements before him as a map, a rule, and a canon. The way of truth is discovered by the external revelation of God’s Word, not inner excavation of the feelings.

The act of choosing is only possible because God has first chosen him. Faith itself is a gift (Ephesians 2:8-9). The psalmist’s choice is not the cause of grace but the fruit of it. This is where Lutheranism differs radically from synergistic systems that emphasize human cooperation. Even our ability to choose the way of truth is the result of the Spirit working through the Word. As we confess about the Third Article of the Creed, “I believe that I cannot by my own reason or strength believe in Jesus Christ, my Lord, or come to Him; but the Holy Spirit has called me by the Gospel, enlightened me with His gifts, sanctified, and kept me in the truth faith.” The self cannot choose rightly until the Spirit breaks it and remakes it. What the world calls self-empowerment, the Spirit calls repentance and new birth (Baptism; John 3:3-8).

So, the Christian, like the psalmist, does not choose truth as an act of self-definition but as an act of Spirit-led surrender. We do not choose truth because we’ve reasoned our way there; we choose it because it has confronted us. We are pierced by the Law and comforted by the Gospel—the double-edged sword of the Word (Hebrews 4:12). The self cannot handle truth on its own; it must be guided, formed, and re-formed by the Word. This is what the psalmist means by laying God’s judgements before him—to follow it toward Christ, not to scrutinize or revise it.

Clinging to God’s Testimonies, Not to Self (v. 31)

“I cling to Your testimonies; O LORD, do not put me to shame!” The psalmist now makes a beautiful contrast: he who once clung to the dust now clings to God’s testimonies. The shift is from false foundations to a true one, not from dependence to independence. Here, the Hebrew word davaq appears again—he once clung to death, and now he clings to the Life. Luther described faith as fides apprehensiva (apprehensive faith)—faith that grabs hold of Christ like a drowning man clings to a rope.

This verse exposes the self-defeating nature of self-help. It tells you to rely on your inner strength, but what happens when that strength inevitably runs out? You can’t just “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” anymore—they’ve worn out and broken! (I’ve experienced this firsthand with an awesome pair of boots.) The psalmist does not try to summon something from within. Instead, he cleaves to what is outside himself—the Word of God. Faith is not about believing in yourself but in believing Christ—in holding fast to God’s promises, even when everything else crumbles—and especially then. “Let not your hearts be troubled,” Jesus says. “You believe in God; believe also in Me” (John 14:1). Christians doesn’t trust in their grip but in the object to which they cling, which is Jesus Christ the Lord.

“O LORD, do not put me to shame!” This cry reveals the humility and vulnerability of true faith. It’s the opposite of the self-help confidence (i.e., pride) that refuses to show weakness. The psalmist knows he has no fallback plan if God fails him. There is no Plan B, for it is not necessary. His hope is entirely placed in God’s Word, and if that Word were to falter (which it cannot), he’d be undone. This is radical trust, not despair—the kind of trust that does not flatter itself but casts itself wholly upon the Lord.

Luther once wrote that faith is “a living, daring confidence in God’s grace, so sure and certain that a man would stake his life on it a thousand times” (LW 35:370-371). That’s what we see here. The self-help mindset cannot produce this kind of faith. It cannot teach the soul to cling to God because it refuses to admit the poverty of the self. Yet the psalmist shows us a better way: cling not to your own meager ability, insights, or strength. Cling instead to the testimonies of the Lord, which are efficacious. There, and only there, is life.

Running, Not Crawling (v. 32)

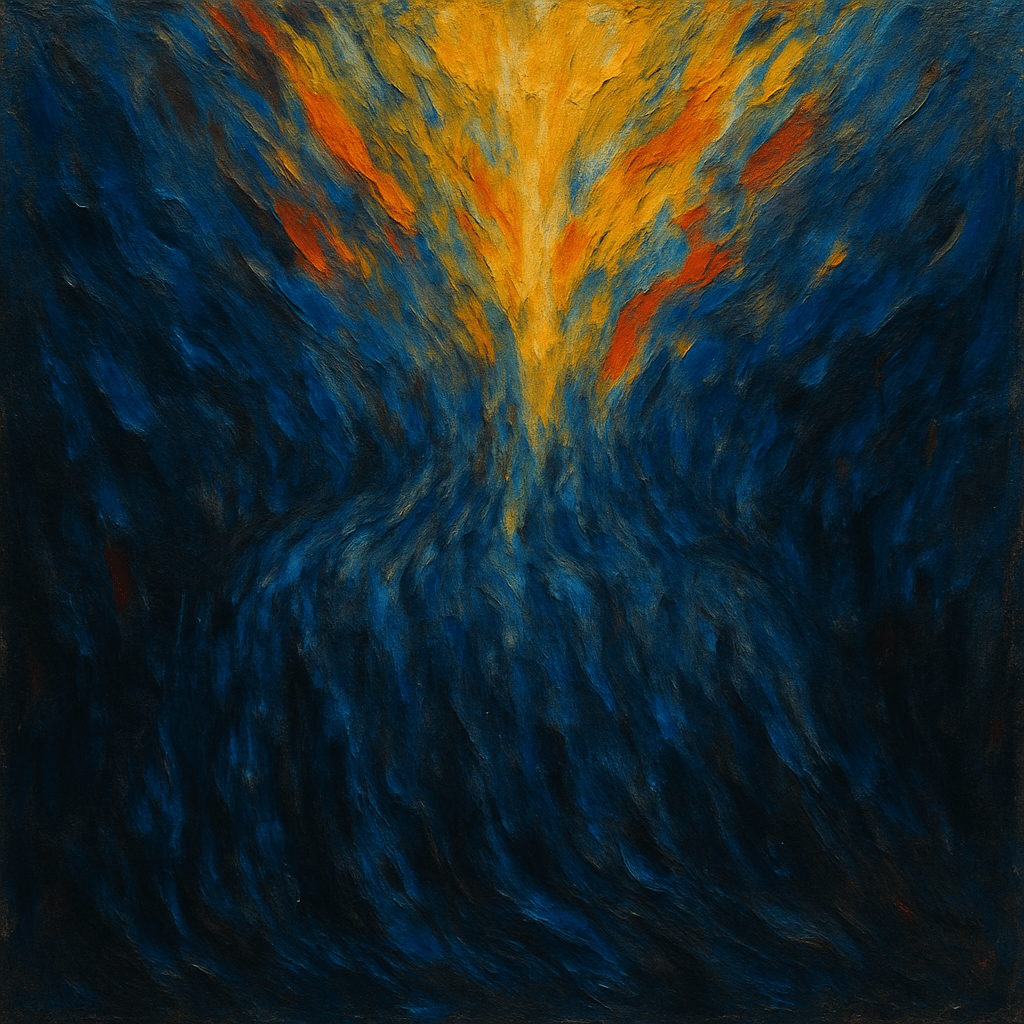

The psalmist ends this section of the acrostic with a stunning picture: “I will run the course of Your commandments, for You shall enlarge my heart.” He’s no longer clinging to dust, no longer melting in sorrow, and no longer entangled in lies. He’s now running—free, jovial, and unburdened. This is the fruit of grace. But notice the order: it is not “I will run, then You will enlarge my heart.” It’s “for You shall enlarge my heart,” and then he runs. Although the clause of his running comes first, it is actuated by God’s enlarging of his heart.

The enlargement of the heart is an image of freedom, received capacity, and spiritual vitality. A small heart is constricted, self-centered, and anxious. A large heart is full of love for God and neighbor; a small heart is full of love of self (pride). This transformation is accomplished by the miracle of grace, not by motivational slogans or ten steps to a better you. Only God can make the heart spacious. The Spirit takes the stony heart and replaces it with one of flesh (Ezekiel 36:26). The psalmist is not boasting in his discipline or drive—he’s rejoicing in what God has done within him.

Self-help psychology often seeks to enlarge our hearts through ego-expansion. “Believe in yourself.” “Unleash your potential.” “Be the best version of you.” It’s not that self-doubt is good and healthy, but Scripture teaches the heart cannot be healed until it is broken, humbled, and remade through the Great Surgeon’s hands. Any earthly surgeon will tell you at-home surgery is foolish. Thus, enlargement of the heart comes not through asserting the self but through crucifying it. The old Adam must be drowned and the new man raised up in Christ (Romans 6:3-6; 2 Corinthians 5:17). Only then does the heart grow wide with love, filled with the Spirit and the joy of obedience.

“I will run the course of Your commandments.” The Christian life is not a burden but a race—a marathon, not a sprint (cf. Hebrews 12:1-3; 1 Timothy 6:12-14). Neither is it a crawl through guilt but a marathon of thanksgiving. We do not run to earn God’s favor—we run because we already have it in Christ. This is the paradox: only when we give up ourselves do we truly begin to live (Matthew 16:24-26). Only when we stop trying to fix ourselves can God truly transform us. This is the life the psalmist embraces. And this is the invitation to every Christian heart: run—not in your strength or to escape reality, but in the freedom God has given you in Jesus Christ our Lord.

Works Cited

Wengert, Timothy J. The Roots of Reform. Edited by Hans J. Hillerbrand, Kirsi I. Stjerna, and Timothy J. Wengert. Volume 1, The Annotated Luther. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2015.