The Context: A Man and A Question about Eternal Life

The context of Mark 10:17-22 is critical for understanding Jesus’ strange statement, “Why do you call Me good? No one is good but One, that is, God.” The man who approaches Jesus is not hostile—he runs and kneels before Him, showing honor and apparent sincerity. Yet his question, “Good Teacher, what shall I do that I may inherit eternal life,” betrays a deeply rooted theological misunderstanding. He sees goodness as a quality possessed by moral effort and assumes eternal life is earned rather than given. In the legalistic framework of first-century Judaism, righteousness was often viewed in terms of law-keeping, and this man had likely been taught by his rabbis to see salvation as a reward for obedience.

Jesus’ reply may seem jarring at first, but He’s not issuing a correction in the way we might rebuke flattery or misplaced honor. Rather, Jesus is doing what He often does—turning a simple question into a deep theological encounter. The man called Him “teacher.” So, Jesus uses this moment to teach Him. He aims to expose the man’s incomplete understanding not just of salvation but of the very One he’s addressing. The man sees Jesus as a good teacher. He is that, but Jesus wants him to see something far more—that He is God in the flesh.

By drawing attention to the word “good,” Jesus reveals how easily we can use divine language superficially. The man speaks rightly—Jesus is indeed good—but he does not grasp the theological weight of that word. To call Jesus “good” is to call Him God, for only God is good in the absolute sense. In this way, Jesus is not deflecting the title but inviting the man to consider what his own words are saying. It’s as if Jesus is saying, “If you truly believe I am good, then recognize what that means—that I am God.”

Jesus also subtly shifts the conversation from what man must do to who God is. This is essential in our theology. We are not justified by our works but by God’s grace alone, through faith alone, in Christ alone (cf. Ephesians 2:8-9). By confronting the man’s casual use of “good,” Jesus is preparing him—and us—for the doctrine of sola gratia (grace alone). Salvation is not about the goodness we offer to God but about the goodness God has shown to us in Christ. Thus, the question should not be, “What must I do,” but “Who is the Good One who can save me?”

Theological Clarification: Jesus is Good because Jesus is God

In Lutheran Christology, we affirm Jesus is vere Deus et vere homo—truly God and truly man. This means He’s not a hybrid or demi-god but fully divine and fully human, possessing two natures in one indivisible person. As our Confessions say, “The divine and human natures in Christ are personally united [the hypostatic union]. So there are not two Christs, on the Son of God and the other the Son of Man. But one and the same person is the Son of God and Son of Man (Luke 1:35; Romans 9:5). We believe, teach, and confess that the divine and human natures are not mingled into one substance, nor is it changed into the other. Each keeps its own essential properties, which can never become the properties of the other nature” (FC Ep VIII, 5-6).

Jesus’ divine nature includes “almighty, eternal, infinite, and to be everywhere present (according to the property of its nature and its natural essence, of itself), to know everything, and and so on [thus, we can include goodness here]. These never become properties of the human nature.” Whereas Jesus’ human nature includes Him “to be a bodily creature, to be flesh and blood, to be finite and physically limited, to suffer, to die, to ascend and descend, to move from one place to another, to suffer hunger, thirst, cold, heat, and the like. These never become properties of the divine nature” (FC Ep VIII, 7-8).

Furthermore, “It is not like when two boards are glued together, where neither gives anything to the other or takes anything from the other. But here is described the highest communion that God truly has with man. From this personal union, the highest and indescribable communion results. There flows everything human that is said and believed about God, and everything divine that is said and believed about the man Christ” (FC Ep VIII, 9).

As such, Jesus is perfectly good, not only in moral action but in His very being, just as God is. This goodness is not derived from obedience, as it would be for a creature, but from His divine nature. Jesus does not become good by what He does; He is good because He of who He is—God incarnate.

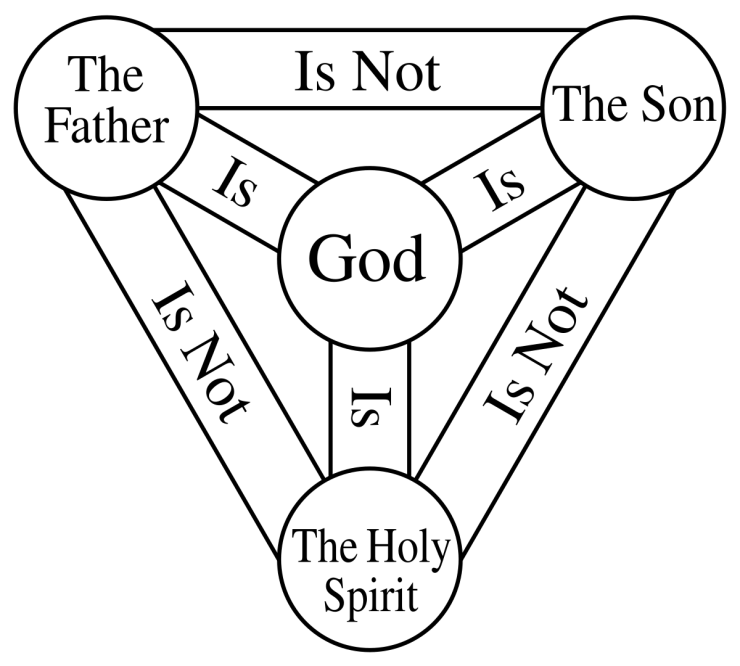

Therefore, when Jesus says, “No one is good but One, that is, God,” He’s not excluding Himself from that statement. Instead, He’s challenging the man—and us—to reconsider what it means to use the word “good” in relation to Jesus. This is not a denial of His divinity but a pointer to it. As we confess in the Nicene Creed, He is “God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father” (see diagram above). If the man truly believes Jesus is good, then he must also come to confess Jesus is God.

Jesus was often misunderstood by those who followed Him, and instead of always declaring His identity outright, He often led people to confession through the pedagogical methods of the day in which they lived. In the true fashion of a rabbi, He asked the man a question to initiate a teaching moment—in this case, “Why do you call Me good?” College, graduate, and doctoral students today experience such pedagogy from their professors all the time to develop critical thinking skills. Jesus is essentially saying: Do you mean what you say? Do you truly believe this Man is good in the sense that only God is good? Jesus is leading this man toward a deeper understanding of Christology.

In denying human goodness and affirming divine goodness, Jesus also upholds the proper order of worship. As Lutherans, we confess worship must be directed only to God, not to moral examples or religious figures. The man’s flattery could be the beginning of idolatry if it doesn’t proceed with orthodoxy (literally: right teaching). Jesus wants more than admiration; He desires faith. His question drives the hearer to the brink of confession so that they may finally see the “Good Teacher” is no mere rabbi but none other than the incarnate God, deserving of all worship and trust.

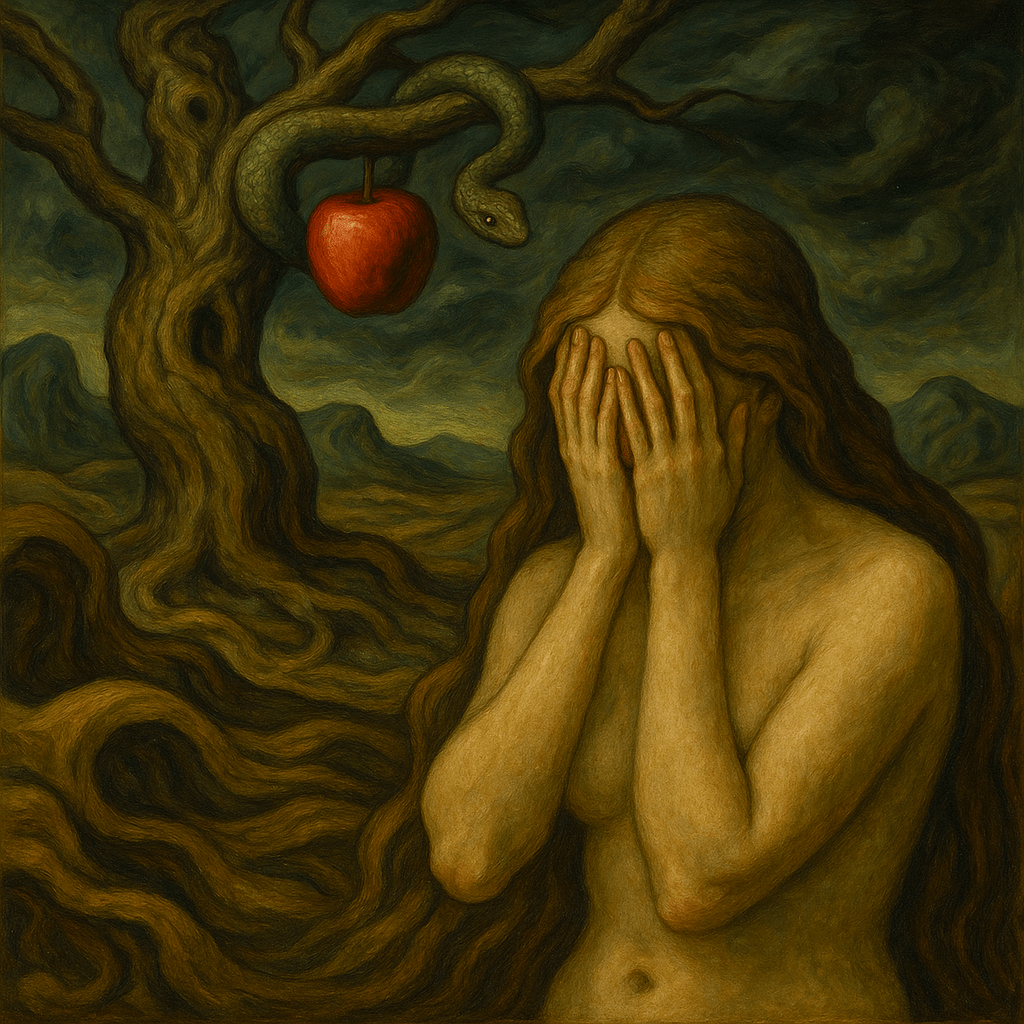

The Nature of Goodness: Not a Human Achievement

This passage powerfully undermines any hope we might have in earning salvation through our own goodness. In both the Psalms and Paul’s epistles, Scripture teaches all have turned away, all have become corrupt; there is no one who does good, not even one (Romans 3:10-12; Psalm 14:3). We echo this in the doctrine of original sin, where we believe, teach, and confess “that since the fall of Adam [Romans 5:12], all who are naturally born are born with sin [Psalm 51:5], that is, without the fear of God, without trust in God, and with the inclination to sin, called concupiscence. Concupiscence is a disease and original vice that is truly sin. It damns and brings eternal death on those who are not born anew through Baptism and the Holy Spirit [John 3:5]” (AC II, 1-2).

So, when Jesus says, “No one is good but One, that is, God,” He’s also making a categorical statement about fallen humanity. Our goodness, such as it exists, is always relative and tainted by sin. Even our best works are polluted by selfishness, pride, or fear. That’s why we confess in the Divine Service, “We are by nature sinful and unclean” (LSB, p. 151). The only way to be declared righteous is to receive an alien righteousness—not one born of our effort but one bestowed by grace through faith in Christ.

In the eyes of many, the man in Mark 10:17 may have seemed righteous—devout, respectful, obedient to the Commandments. But Jesus sees deeper. The man’s goodness is only surface-level; it’s not rooted in the confession that God alone is good. By dismantling his illusions, Jesus is inviting him to receive a goodness that cannot be earned but only gifted: the righteousness of God that comes through faith (Romans 3:22).

This is where the Lutheran distinction between Law and Gospel becomes so vital. The Law says, “Do this and you shall live.” But the Gospel says, “It is finished, and now you live.” Jesus’ words in Mark 10:18 function as Law—they condemn the idea that we can be good enough for God, but they also prepare our hearts for the Gospel: that Christ, the only Good One, became sin for us so that we might become the righteousness of God in Him (2 Corinthians 5:21). Only in the Gospel is the goodness of God not a threat but a gift.

The Humility of Jesus: Concealing His Glory for Our Sake

Jesus’ question also reflects His earthly humility. In His state of humiliation (Philippians 2:5-11), Jesus did not always exercise full use of His divine power. Though He remained fully God, He subjected Himself to suffering, limitation, and even misunderstanding. This was not a flaw or weakness but a necessary part of His redemptive mission. He came to serve, not to be served, and to give His life as a ransom for many (Mark 10:45). His humility is not the absence of divinity but its perfect expression.

By veiling His glory, Jesus invites faith, not coercion. He does not overwhelm with divine brilliance but wins hearts through mercy and truth. In Mark 10, His question becomes a quiet yet thunderous call: See who is speaking to you. Understand what you’re saying, and believe. The same humility that led Him to ask this question will soon lead Him to the cross where the goodness of God will be poured out in blood.

This paradox—the God who hides, the Good who is crucified—is at the center of Lutheran theology. We see it in the theology of the cross, where divine strength is hidden under suffering and glory comes through shame. Jesus asking, “Why do you call Me good,” is a moment of divine self-concealment that invites a deeper revelation: this Man, who refuses flattery, is the exact image of the invisible God (Hebrews 1:3).

Indeed, it is precisely because Jesus is humble that we can trust His goodness. He does not assert Himself with worldly power and pride but draws near in meekness. If He came to us as CEO, we would not trust Him; but He came to us as Shepherd, so we therefore trust Him as our Good Shepherd (John 10:11-18). The same Lord who asks this question is the Shepherd who seeks the lost, the Physician who heals the sick, and the Bridegroom who lays down His life for His Bride, the Church. His question is not distancing but invitational: Come and know the Goodness of God made flesh.

We Call Jesus Good because We Confess Him as Lord

What does it mean, then, to call Jesus good today? It is not a throwaway compliment like the man was doing but a confession of faith. To say “Jesus is good” is to say “Jesus is God.” It is to worship the One who alone fulfills the Law, who is without sin, and who’s the exact imprint of the Father’s divine essence. Christians do not flatter Jesus; we confess Him. Our liturgy, prayers, and hymns are all ordered around the conviction that Jesus is the Good One sent by the Father for our salvation. As Luther wrote, to call Jesus Lord “means simply the same as redeemer. It means the One who has brought us from Satan to God, from death to life, from sin to righteousness, and who preserves us in the same” (LC II, 31).

This goodness is not abstract but deeply personal to Christ’s divine nature. It’s the goodness that forgives sins, comforts the grieving through the Gospel, and carries the cross in our place for our atonement. The Good Shepherd lays down His life for the sheep. The Good Physician binds up the brokenhearted. The Good Teacher opens our minds to understand the Scriptures. When we call Jesus good, we’re not merely echoing the words of the man who knelt before Him—we’re speaking as those who’ve been redeemed, justified, and made whole by grace through faith.

Mark 10:18 therefore teaches us not only about Christ’s divinity but also about our own identity in Him. Since only God is good, and we are baptized into Christ, then we share in His goodness—not as our own possession but as a gift. We do not become little gods; we become beloved children, clothed in Christ’s righteousness and made heirs of eternal life (Galatians 3:26-27, 29).

Therefore, the true takeaway from Jesus’ question is not doubt but devotion. Only God is good, and that Good God has come down to us in Christ. The hands that broke bread for the five thousand, that touched lepers, that were pierced for our transgressions belong to the Good One. We rejoice in His goodness not as spectators but as those who’ve been saved by it. And in every act of praise, we proclaim the truth that changes everything: Jesus is good, for Jesus is God.