“ ‘Your hands have made me and fashioned me, an intricate unity; yet You would destroy me.’” — Job 10:8

Prayer or Protest?

Job 10 is both a prayer and a protest. It’s the second part of Job’s long reply, and while chapter 9 pondered God’s transcendence and the impossibility of confronting Him, chapter 10 dares to speak to Him directly. Job is not resigned. He is not mute. He brings his anguish into God’s presence and demands answers—not in rebellion, but in desperate faith. That faith is the key here.

This chapter continues to give voice to those who suffer silently. Job challenges the hiddenness of God not because he rejects Him, but because he longs for a God who sees, speaks, and explains. This is not an atheist’s rant—this is a believer’s lament.

Job begins by demanding God show him the reason for his suffering: “I will say to God, ‘Do not condemn me; show me why You contend with me’” (v. 2). This sets the tone for the chapter. Job assumes God is just but cannot reconcile that justice with his own condition. He believes if God would only explain Himself, Job would accept it. But no explanation is given.

He then asks a series of cutting rhetorical questions: “ ‘Does it seem good to You that You should oppress, that You should despise the work of Your hands, and smile on the counsel of the wicked? Do You have eyes of flesh? Or do You see as man sees? Are Your days like the days of a mortal man? Are Your years like the days of a mighty m an, that You should seek for my iniquity and search out my sin?’” (vv. 3-6). These are not questions seeking information—they are cries seeking mercy. Job does not believe God is like man, but in the fog of his pain, he wonders why God seems to act like one—petty, aggressive, and myopic.

In his torment, Job begins to accuse God of injustice, not in rejection of faith, but from within the framework of it. This is the paradox: only someone who truly believes in God’s justice can feel its absence so acutely. However, once again, he justifies himself before God, “Although You know that I am not wicked, and there is no one who can deliver from Your hand?” (v. 7). To reiterate, Job is not claiming to be sinless. He’s maintaining his true integrity before his friends’ false accusations, but at the same time makes himself the justifier rather than God (Romans 3:26).

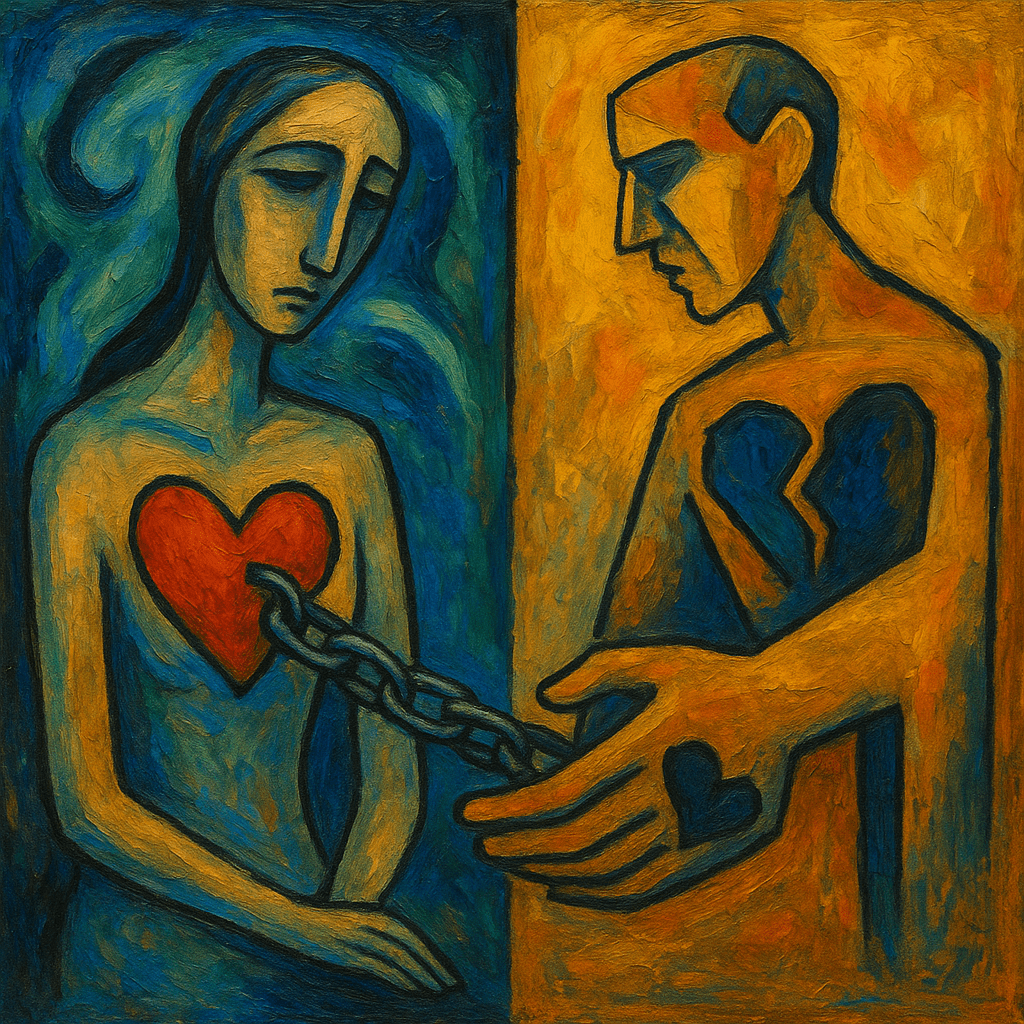

The most haunting part of this chapter comes in verses 8-12. Job recalls his creation in tender imagery: “ ‘Your hands have made me and fashioned me, and intricate unity; yet You would destroy me. Remember, I pray, that You have made me like clay. And will You turn me into dust again? Did You not pour me out like milk, and curdle me like cheese, clothe me with skin and flesh, and knit me together with bones and sinews? You have granted me life and favor, and Your care has preserved my spirit.’” He speaks of God as his Creator, as the One who lovingly shaped every part of his body and soul.

But this memory of divine care only deepens his pain. “Yet You would destroy me,” he says (v. 8). Job cannot understand how the same God who formed him with such care would not turn against him in such apparent wrath. It feels like betrayal. If God made him with such intention, why does He now crush him? Job is boldly holding God accountable to His creation. The God who made him, he insists, must also care for him. But all Job sees is destruction.

For pastors, this speaks to the intense theological crisis suffering can bring. A believer may affirm God’s sovereignty and love, but when affliction strips away all comfort, even the foundational truth of being made in God’s image can feel like a cruel irony. To have been so intricately designed, only to be so violently undone, is a torment that demands lament.

Conditional Love?

Job’s boldness continues as he begins to question whether God’s love was ever genuine: “ ‘And these things You have hidden in Your heart; I know that this was with You…’” (v. 13). He wonders if God had planned all along to condemn him—if the love shown in his creation was only a setup for later judgement. Then he states, “ ‘If I sin, then You mark me, and will not acquit me of my iniquity. If I am wicked, woe to me; even if I am righteous, I cannot lift up my head. I am full of disgrace; see my misery!” (vv. 14-15). Job feels trapped in a no-win situation. If he sins, he’s punished. If he does not sin, he still suffers. Righteousness brings no vindication, only more shame. He has no access to relief, no opportunity for a fair trial, and no hope of parole.

Job is voicing the existential pain of living under affliction without clarity. It’s not just the physical suffering that hurts—it’s the perceived futility of any moral effort. In a world governed by such suffering, righteousness seems irrelevant. This, too, is part of pastoral care: recognizing those in long-term pain often come to feel not just physically broken but also spiritually stuck. When even their integrity feels futile, we must bring them not commands but Christ.

Here, Job exposes one of the most corrosive lies that afflict the soul in suffering: the fear that God’s love is transactional. He wonders if God ever loved him freely, or if divine affection was always dependent on his performance. Job fears he’s living in a rigged system—a covenant of conditional affection where obedience earns warmth and affliction proves rejection. This fear still lingers in the minds of many Christians today, especially those suffering from chronic pain, mental illness, or depression. They begin to ask: What if God’s promises only applied when I was useful, successful, or faithful?

But the Gospel reveals a love entirely unlike what Job fears. In Christ, the love of God is revealed to be unconditional, rooted not in our performance but in His mercy. The God who knows our frame and remembers we are dust does not withdraw affection when we falter—He draws near. The cross stands as the eternal witness that God’s love is not revoked in our suffering but most fully displayed in it. Job does not yet see this, but his question makes room for its ultimate answer: a love that is not hidden in God’s heart, but poured out in Christ’s wounds.

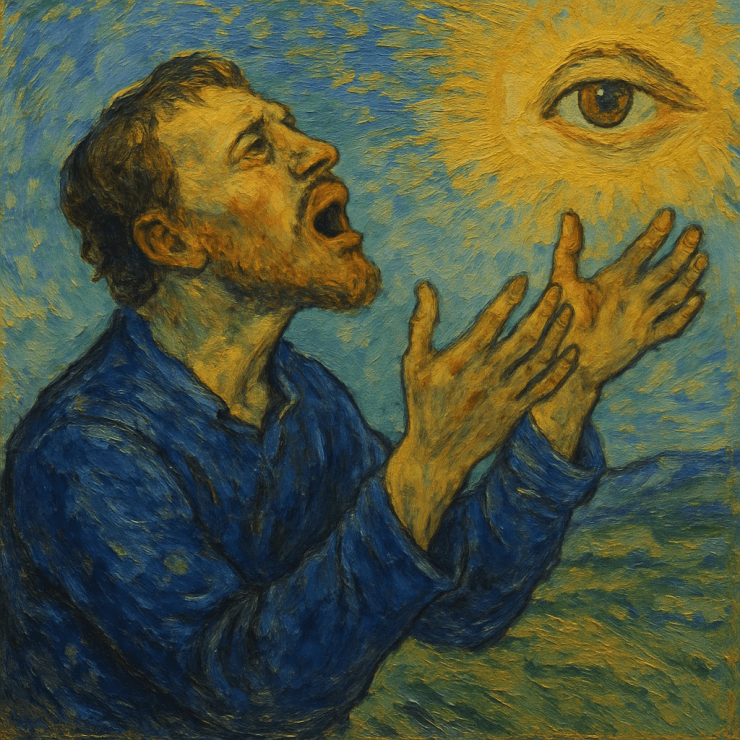

The Dread of Divine Surveillance

Job then shifts to God’s omnipresence, but instead of being comforted by it, he feels hounded. “ ‘If my head is exalted, You hunt me like a fierce lion, and again You show Yourself awesome against me. You renew Your witnesses against me and increase Your indignation toward me; changes and war are ever with me’” (vv. 16-17). Job envisions himself as prey, pursued by God, unable to escape His scrutiny.

This is a distorted view, but it’s the honest distortion of a heart crushed under divine silence. When God does not speak in grace, His presence becomes terrifying. Omniscience without mercy is unbearable. What should be a comfort (“God sees me”) has become a cause for despair: “God sees me and does nothing.”

Job’s experience here echoes a common psychological and spiritual burden: the feeling of being under constant divine inspection, as if every word, thought, or misstep is recorded against the soul. For those who suffer and can find no explanation, this sense of surveillance turns God from a Father into a warden. The sinner already overwhelmed by life begins to believe Heaven’s eye is always disapproving, watching not in love but in suspicion. This is not how God truly watches His children—but in the darkness of despair, it often feels that way.

What Job cannot yet see—and what we proclaim through the Gospel—is that God’s gaze in Christ is not one of judgement but of compassion. Jesus is the Mediator who turns the eyes of the Father toward mercy. In Christ, the omniscient gaze that once terrified becomes a source of peace. It’s the same gaze that searched for Adam in the Garden, the same that wept over Jerusalem, the same that looked upon the thief on the cross. For the believer, divine attention is not surveillance but care. But Job, without the full revelation of Christ, groans under the weight of a God who seems to see everything and speak nothing.

Why Was I Born?

Job ends where he began in chapter 3—with the wish he’d never been born. “ ‘Why then have You brought me out of the womb? Oh, that I had perished, and no eye had seen me!’” (v. 18). He desires not death itself, but nonexistence. He wishes to undo creation, to erase the pain by erasing himself.

“ ‘Are not my days few? Cease! Leave me alone, that I may take a little comfort, before I go to the place from which I shall not return, to the land of darkness and the shadow of death, a land as dark as darkness itself, as the shadow of death, without any order, where even the light is like darkness’” (vv. 20-22). These closing lines are devastating. Job begs God to look away so that he may find a final, fleeting peace before death claims him. He believes God’s gaze only brings further torment. So, he prays for reprieve instead of rescue—not for life, but for the space to die quietly.

Job 10 offers no easy answers. It is theology under pressure—faith in the furnace. It contains accusations, laments, and pleas—yet all are directed to God, which is itself an act of faith. From a Christian perspective, Job’s experience points forward to the One who was also formed in the womb, only to be forsaken by the Father on the cross. Jesus also cried out, “Why?” He also felt abandoned. But unlike Job, Jesus bore the sin Job only feared.

Where Job cries, “Why have You made me just to destroy me,” Jesus becomes the one who was made to be destroyed for our sake. And through that destruction, resurrection and redemption came. The answer to Job’s cry is not philosophical—it is incarnational. The Creator took on flesh not only to redeem, but to be crushed, so that even in our cries we are not alone.

This chapter is a sacred text for those whose prayers feel unanswered and whose lives feel ruined. It assures the Church that lament is not profanity but a form of prayer. It teaches pastors not to silence the grieving but to stand with them and speak of the God who was once forsaken so that we never truly are. This is the mystery of faith: that we may speak boldly to the God who seems absent, trusting that even silence is not rejection—and that behind the darkness stands a cross-shaped love that does not let go.