“For He is not a man, as I am, that I may answer Him, and that we should go to court together. Nor is there any mediator between us, who may lay his hand on us both.” — Job 9:32-33

Reverence in the Midst of Reproach

In response to Bildad’s rigid proclamation of retributive justice, Job does not lash out in bitterness, which is surprising. Instead, he expresses something far more complex—an awe-filled despair. He begins by affirming what Bildad said about God’s justice in theory: “Truly, I know it is so, but how can a man be righteous before God?” (v. 2). Job does not deny God is just. He doesn’t claim to be without sin in an ultimate sense. Rather, he questions how any mere human could ever stand before such a transcendent and terrifying God.

What follows is a breathtaking meditation on divine power. Job speaks of God’s unsearchable greatness: “He removes the mountains, and they do not know when He overturns them in His anger; He shakes the earth out of its place, and its pillars tremble” (vv. 5-6). He describes the One who commands the sun, who stretches out the heavens, who walks on the waves, and who created the constellations (vv. 7-9). God, Job says, is sovereign over all reality—and utterly beyond human intelligence.

There’s no doubt Job fears God in the truest biblical sense, but this fear is not yet joined with comfort. It is unreconciled terror, not peace, that defines Job’s experience here. He knows God is holy. He knows God is unfathomably powerful. What he cannot see is how such a God could possibly be for him.

When God Becomes the Opponent

In verse 14-20, Job envisions a courtroom where he must face God as an accuser: “How then can I answer Him, and choose my words to reason with Him? For though I were righteous, I could not answer Him; I would beg mercy of my Judge” (vv. 14-15). Even if Job were in the right, he believes he still could not win against God’s overwhelming majesty. This section reveals the paradox that plagues Job: he believes in God’s justice, yet he also believes he’s suffering unjustly. He cannot reconcile the two. So, he imagines himself pleading for mercy instead of vindication—even if the charges are false.

Yet once again, he justifies himself before God, “I am blameless, yet I do not know myself; I despise my life. It is all one thing; therefore, I say, ‘He destroys the blameless and the wicked’” (vv. 21-22). As seen earlier in chapter 6, by maintaining his integrity before his friends (which is true), he at the same time justifies himself before God instead of relying on the Lord’s justification, which we will see at the end of the book.

More painfully still, Job describes God as an adversary: “If I say, ‘I will forget my complaint, I will put off my sad face and wear a smile,’ I am afraid of all my sufferings; I know that You will not hold me innocent” (vv. 27-28). He feels condemned no matter what he does. He cannot pretend to be cheerful. He cannot erase the pain. Even if he tries to be brave, the suffering remains—and God, it seems, does not relent.

This perception of God as both judge and tormentor reflects the psychological weight of suffering. When affliction is prolonged and Heaven is silent, even the believer may begin to see God not as refuge, but as pursuer. Job is not rejecting faith—he is fighting to hold onto it in the dark.

The Absence of a Mediator

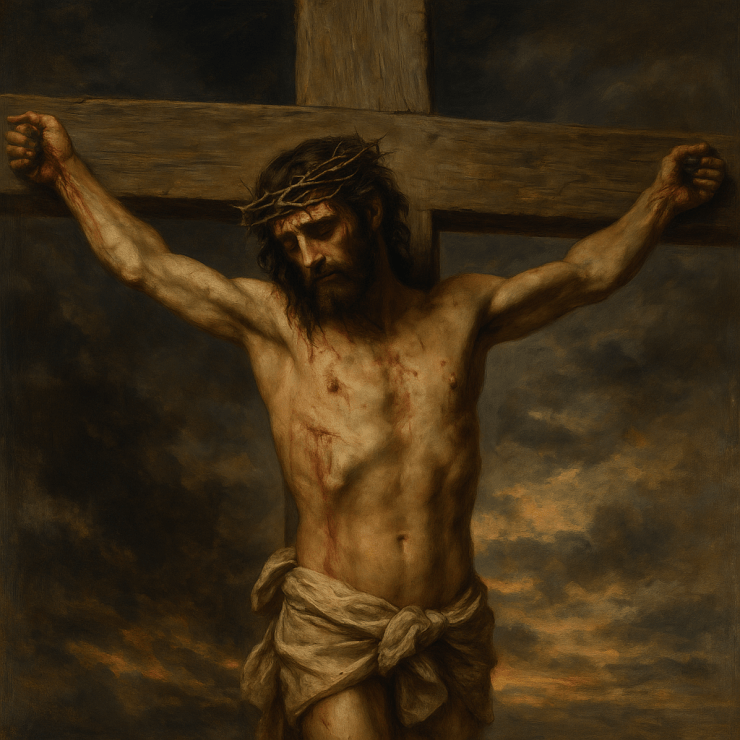

The climax of Job’s cry comes in verses 32-33, “For He is not a man, as I am, that I may answer Him, and that we should go to court together. Nor is there any mediator between us, who may lay his hand on us both.” Here, Job articulates a deep human longing—a desire for someone who can bridge the infinite gap between God and man. He wishes for an arbitrator, someone who can interpret God to him, and him to God. He desires someone who can stand in the breach, lay a hand on both the sinner and the Holy One, and reconcile them.

Job has no idea this longing will one day be fulfilled in Jesus Christ, the one Mediator between God and man (1 Timothy 2:5). Job’s despair is a shadow of the very thing the Incarnation answers. The infinite God did become man. The holy Judge did come in mercy. The one Job longs for already stands on the horizon of redemptive history, so that it would be said, “For if when we were enemies we were reconciled to God through the death of His Son, much more, having been reconciled, we shall be saved by His life. And not only that, but we also rejoice in God through our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom we have now received the reconciliation” (Romans 5:10-11).

But Job doesn’t see that yet. He only sees the unbreachable chasm between God and man. He longs for closeness with God but feels only estrangement. And because he cannot bridge the gap, he believes there is no way forward.

A Theology for Those in the Dark

This chapter offers an honest theology for the afflicted. Job’s questions are not academic—they’re deeply personal. How can a person commune with a God who feels like the enemy? How can the finite endure the attention of the infinite? How can anyone plead their case before One who already knows everything?

The Church must honor these questions. Too often, sufferers are told to trust without wrestling, to pray without complaint, or to submit without speaking. But Job models a deeper kind of faith—a faith that speaks to God even when it doubts, a faith that laments while still believing. Job is not a cautionary tale; he’s the model for our own lamenting.

From a pastoral perspective, we must never shame the one who asks such questions. Instead, we can walk with them, echo their cry, and point gently to Christ—not as an easy answer to suffering, but as the Mediator who hears it and joins them in it.

Here, we see Job as a theologian of the cross. He explores the hiddenness of God—His power, His distance, His incomprehensibility. But unlike the theologian of glory, he does not attempt to resolve the tension. Job’s longing remains unanswered, for the theologian of the cross is willing to say to life’s deepest questions, “I don’t know.” But we, who read this through the cross and resurrection, know Job’s cry was not in vain.

The New Testament reveals that what Job begged for—a Mediator—has been given. Jesus Christ, true God and true man, lays His hand on both divinity and humanity in His incarnation. He not only speaks for us to the Father, but He is the Word of the Father made flesh for us (John 1:1, 14). He does not merely argue our case—He bears our punishment and pleads our cause with His innocent blood.

Thus, what Job could only dream, the Church now proclaims. We have a High Priest who sympathizes with our weaknesses and enables us to confidently approach the throne of grace (Hebrews 4:14-16). We have a Savior who stood silent before His accusers so that we might speak boldly to our Father. We have a God who answers, even when His answer comes wrapped in cross and silence.

Job 9 does not end in comfort; it ends in isolation. But that isolation is not unbelief; it’s a yearning for God so deep, so holy, and so honest that God Himself will one day answer it through a body and a cross. When the Church reads Job 9, we do not correct Job—we join him. We echo his cry. And we trust, as Job eventually will, that the God who seems unreachable has already drawn near in Jesus Christ.

1 thought on “Job 9: The God I Cannot Reach”