The Church’s Tragic Complicity and a Call to Repentance

The history of racism and slavery in the Church is not a tale of biblical fidelity but of biblical distortion. For centuries, Scripture was wielded not as a sword of the Spirit but as a weapon of human oppression. The transatlantic slave trade and the racial segregation under Jim Crow laws in the United States were often justified with twisted proof texting and theological arguments that obscured the heart of the Gospel. The Church must reckon with its failures in this regard, including some Lutherans’ failure to denounce Hitler during his evil regime (note: many did openly resist, such as the American-German Lutheran soldiers who fought and died in WWII, the LCMS, and the Confessing Church, including the famous Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer). Repentance is not merely an acknowledgement of past sin but also a turning away from it through the power of the Holy Spirit.

Our Lutheran Confessions remind us that the Church is semper reformanda, always reforming according to God’s Word. Thus, we cannot be content with historic apologies; we must actively reject every remnant of racism in our congregations, our liturgies, and our communities. Where the Gospel is truly preached, it breaks down barriers, not builds them. Where Christ is rightly proclaimed, He gathers into one all the scattered children of God.

This study aims to dismantle the false theological structures that have upheld racial slavery and segregation. We’ll do this not by appealing to modern sensibilities but by returning to Scripture and the Lutheran Confessions. We’ll also listen to faithful Black theologians and scholars, not to supplement the Word of God but to highlight how its truth has always spoken against these evils. The goal is not merely to condemn past sins but to strengthen the Church’s witness to the unity of the Body of Christ.

Slavery in Scripture: Descriptive, Not Prescriptive

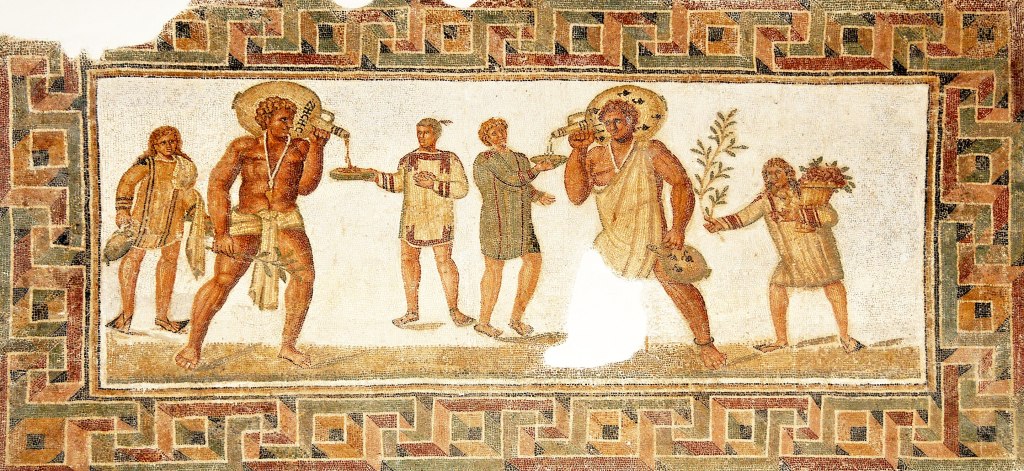

One of the most frequently cited texts to justify slavery is Ephesians 6:5, in which Paul instructs slaves to obey their masters. However, a contextual reading reveals Paul was not endorsing slavery but regulating an existing social structure with the aim of transforming it from within. Roman slavery was not race-based but socio-economic, and many slaves held important and skilled positions, not that this makes it any more right, hence Paul’s exhortations. To read modern racial chattel slavery back into these texts is an anachronistic error. The very term “slave” must be carefully understood within its first-century Greco-Roman context.

Paul’s exhortation to masters in Ephesians 6:9 also disrupts any claim that slavery is biblically sanctioned: “And you, masters, do the same things to them, giving up threatening, knowing that your own Master also is in Heaven, and there is no partiality with Him.” This verse levels the social hierarchy by reminding masters that they, too, are under the authority of the Master: Jesus Christ. They are His slaves; therefore, treat your own as He has treated you (see Romans 6:15-23). The mutual accountability Paul describes here subtly undermines the very foundation of slavery as a permanent hierarchy.

The most powerful biblical refutation of slavery is found in Paul’s epistle to Philemon. Paul does not command Philemon to free Onesimus, but he does appeal to him to receive him “no longer as a slave but more than a slave—a beloved brother” (Philemon 16). This redefinition of identity in Christ challenges the legitimacy of the master-slave relationship among Christians. Paul could have exercised apostolic authority, but he chooses instead to appeal on the basis of love, modeling the transformation the Gospel works in human relationships.

Galatians 3:28 serves as a theological climax in the New Testament’s teaching on human ontological equality: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” This verse is not merely a spiritual abstraction (nor is it a denial of the differences between two categories); it’s a radical proclamation of ontological equality in the eyes of God. Any reading of Scripture that finds a mandate for slavery has missed the central message of the cross and the resurrection.

Another text often cited in support of racial slavery is Leviticus 25:39-46. In this passage, God gives instructions to Israel regarding servitude among fellow Israelites and foreigners. Verses 39-43 emphasize an Israelite who becomes poor and sells himself is not to be treated as a slave but as a hired worker. He’s to be released in the Year of Jubilee and is not to be ruled over with rigor. This reveals God’s concern for protecting the dignity of fellow covenant members and limiting servitude among them.

However, verses 44-46 address the case of acquiring bondservants from the nations around Israel:

” ‘And as for your male and female slaves whom you may have—from the nations that are around you, from them you may buy male and female slaves. Moreover, you may buy the children of the strangers who dwell among you, and their families who are with you, which they beget in your land; and they shall become your property. And you may take them as an inheritance for your children after you, to inherit them as a possession; they shall be your permanent slaves. But regarding your brethren, the children of Israel, you shall not rule over one another with rigor.

Critics of Christianity have pointed to this as divine endorsement of chattel slavery. But a closer examination shows even this regulation was within a specific theocratic and agrarian context, not a racial one—and therefore that they fail to distinguish description from prescription. It’s significant that the foreign servants mentioned here were incorporated into the covenant community and were expected to rest on the Sabbath (Exodus 20:10), and that they could partake in the Passover if circumcised (Exodus 12:44). These regulations indicate an assumption of inclusion, not exclusion.

Moreover, Leviticus 25 must be read in light of the overarching biblical narrative of liberation. God identifies Himself as the one who delivered His people from slavery in Egypt (Leviticus 25:38). The entire Jubilee system was instituted to prevent perpetual generational oppression. Thus, even the provisions for foreign servants existed within a framework where mercy, justice, and remembrance of Israel’s own deliverance were central. The Bible does not endorse slavery as an eternal or even natural condition but as a temporary social reality within a fallen world, always regulated by God’s justice and pointing toward freedom.

Finally, the New Testament radically reorients all such social structures through the lens of Christ. In the Church, as we’ve already seen, there’s no longer Jew or Gentile, slave or free. All are equally redeemed and made children of God. The Gospel is the great equalizer. To use Leviticus 25 to justify modern racial slavery, therefore, is to tear it from its redemptive-historical context and to ignore the trajectory of Scripture toward liberation and ontological equality in Christ. Such misuse is not only hermeneutically unsound but also morally bankrupt.

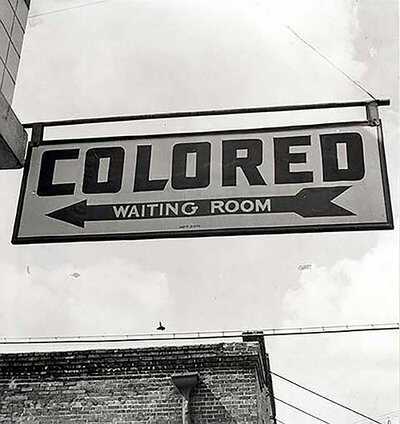

The Sin of Racial Segregation in the Church

If you pay any attention to the unfortunate side of Lutheran Twitter, you may be aware there are some White “Lutherans” who advocate for segregation of believers based on skin color—that each should have their own church body. The sin of racial segregation in the Church (and society) denies the very nature of the Gospel. When St. Paul declares in 1 Corinthians 12:13 that “by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body—whether Jews or Greek, whether slaves or free,” he’s not speaking metaphorically. Baptism is not a symbolic act, as we Lutherans know quite well, but a sacramental incorporation into the Body of Christ (see Romans 6:1-14). To introduce racial divisions into the Church is to reject what God has joined together.

Racial segregation at the altar rail—or in Christendom generally—is not merely a social issue; it’s a major doctrinal error. To deny a baptized believer full fellowship based on race is to deny the efficacy of Baptism itself. It is to say, in effect, that Christ’s righteousness is insufficient to overcome human distinctions. This stands in direct contradiction to Lutheran teaching that Baptism gives new birth, confers the Holy Spirit, and makes one a member of the holy catholic (universal) Church. Those who call for a segregated Church, therefore, fail to confess this Third Article of the Creed. Furthermore, they would have to admit Christ’s incarnation was a salvific failure (Note: they also fail to account for the fact that our Savior—the head of the Church—is a Jewish God-man.)

Even Martin Luther understood the Church as a spiritual fellowship of faith, not of blood or nationality. In the Large Catechism, he writes, “the Spirit has His own congregation in the world, which is the mother that conceives and bears every Christian through God’s Word [Galatians 4:26]” (LC II, 42). This means every baptized believer, regardless of skin color, shares the same divine parentage and the same inheritance. To divide the Church along racial lines is to deny her maternity—to deny she is the mother of all the faithful.

Segregation also contradicts the Lord’s Supper. In the Sacrament, we receive the true body and blood of Christ for the forgiveness of sins, life, and salvation, and we are united not only with Christ but also one another. As Paul says in 1 Corinthians 10:17, “For we, though many, are one bread and one body; for we all partake of that one bread.” Not two bodies, or two churches—but one. Any division at the Lord’s Table is blasphemy against this unity, and any segregation of members within the Church is to divide Christ. Indeed, it is a Nestorian error that preaches not one but two Christs.

Interracial Marriage: No Biblical Prohibition

Some who oppose interracial marriage cite Old Testament laws like Deuteronomy 7:3-4, which prohibits Israel from marrying certain foreign nationals. But the reason given is not racial purity but religious fidelity: “For they will turn your sons away from following Me, to serve other gods” (v. 4). The concern was idolatry, not ethnicity. To apply these verses to modern interracial Christian marriages is to misinterpret the text entirely.

The example of Moses (a Hebrew), who married a Cushite woman (an African), further disproves any racial prohibition. In Numbers 12:1, Miriam and Aaron cricitize Moses for his marriage. God responds by calling them out, descending in a pillar of cloud, and punishing Miriam with leprosy. This divine response makes it clear their objection based on her race was sinful. God does not rebuke Moses; He defends him. His silence on the interracial nature of Moses’ marriage and His anger at the racist critics speaks volumes.

Another Old Testament text often misused to support interracial marriage (and racial segregation) is the account of Ham and the curse of Canaan in Genesis 9:20-27. Such an interpretation is of the utmost folly. The adversaries teach this curse marks Ham’s descendants—especially Africans—as destined for perpetual servitude and exclusion. However, the text does not support such a ludicrous conclusion. The curse is directed specifically at Canaan, not Ham, and it never mentions skin color or race. It’s a prophecy about future conflict among Ancient Near Eastern nations, not a divine mandate for racial hierarchy.

The so-called “curse of Ham” is a tragic example of eisegesis—reading into the text something that’s not there. It was popularized during the era of the slave trade to give theological cover to white supremacy and remains one of the most grotesque distortions of Scripture in church history. I think even the devil is impressed by this. There’s no biblical support for the idea that any racial group is inherently cursed or inferior. The Bible consistently affirms the dignity of all people as imager-bearers of God.

Furthermore, the descendants of Ham include nations of Egypt and Cush, which played significant roles in biblical history. The presence of African peoples in the biblical narrative is not marginal but central. When modern readers claim this ancient episode justifies separation or prohibits interracial marriage, they’re not preserving the authority of Scripture but profaning it through cultural and racial bias in the effort to justify their sin.

Lastly, in 1 Corinthians 7:39, St. Paul gives only one criterion for marriage: that it be “in the Lord.” This means believers may marry any fellow believer, regardless of race or ethnicity. To add racial qualifications to this biblical mandate is to impose a manmade law. The Lutheran Confessions condemn such legalism. As stated in the Apology of the Augsburg Confession:

We must keep in the Church the doctrine that we receive the forgiveness of sins freely for Christ’s sake, through faith. We must also keep the doctrine that human traditions are useless services and, therefore, neither sin nor righteousness should be placed in meat, drink, clothing, and like things… Therefore, the bishops have no right to enact traditions in addition to the Gospel, so that people must merit the forgiveness of sins, or that they think are services that God approves as righteousness. They must not burden consciences…

Ap XXVIII, 7-8; emphasis mine.

The unity of Christian marriage lies not in cultural sameness but in shared faith. Interracial marriages between Christians testify to the power of the Gospel to transcend human boundaries. They proclaim the love of Christ is stronger than the divisions of men. To prohibit such union is not only unbiblical but demonic.

Voices from the Black Church and Theological Tradition

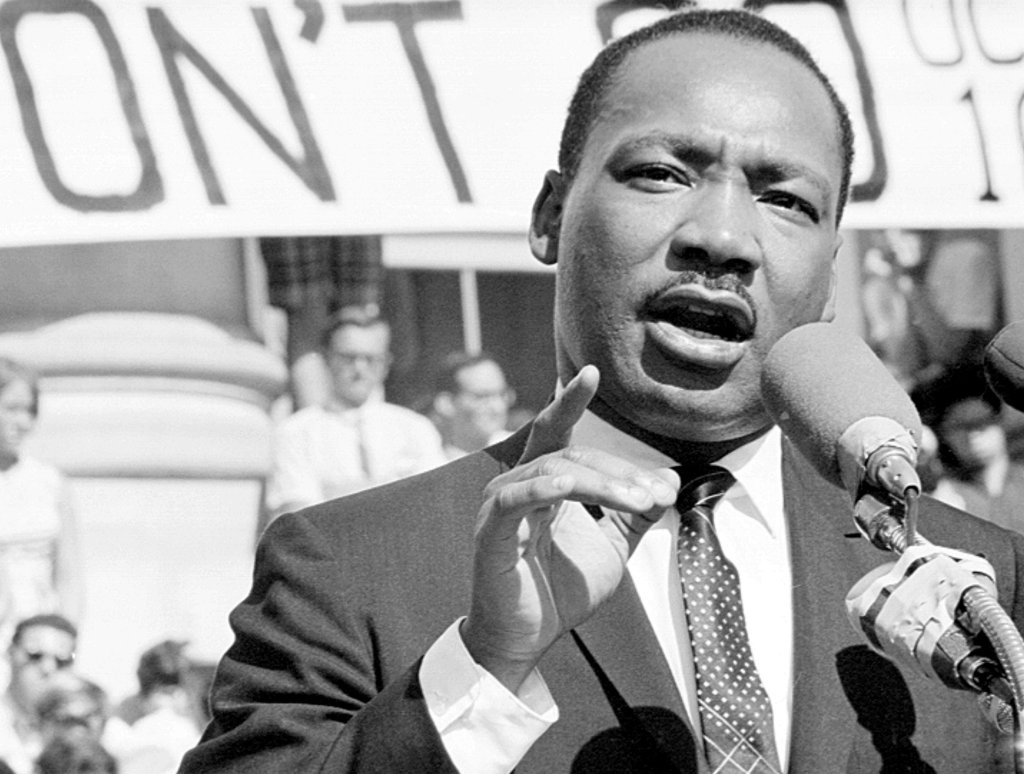

The experience and wisdom of Black theologians offer a powerful witness to the truth of Scripture. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., though ironically not Lutheran, spoke with biblical clarity when he wrote: “Segregation is not only politically, economically, and sociologically unsound, but it is morally wrong and sinful.” His words resonate with James 2:1, “My brethren, do not hold the faith of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Lord of glory, with partiality.”

Dr. King understood segregation was not merely a political arrangement but also a theological affront. When churches exclude on the basis of race, they deny the imago Dei in their fellow believers. This is not a matter of civil rights alone but of divine truth. The Church must not only decry racism but help to dismantle the structures that perpetuate it.

Though White, Rev. Dr. Albert B. Collver III rightly observed, “Segregation is not only a political problem, but a doctrinal problem when it infects the fellowship of the altar. Christ’s body cannot be divided at the rail.” Collver points to the heart of the issue: the unity of the Church is sacramental, not sentimental. When racial barriers are erected at the Lord’s Table, they violate the Means of Grace themselves.

Dr. Esau McCaulley, a Black Anglican theologian, also affirms this vision. In Reading While Black, he writes, “When the Bible speaks of nations gathering before God, it doesn’t erase ethnic identity—it glorifies it… But the emphasis is on worshiping God together, not segregated by tribe.” The biblical vision is one of unity in diversity, not uniformity. The Church is called to reflect this in her worship and fellowship.

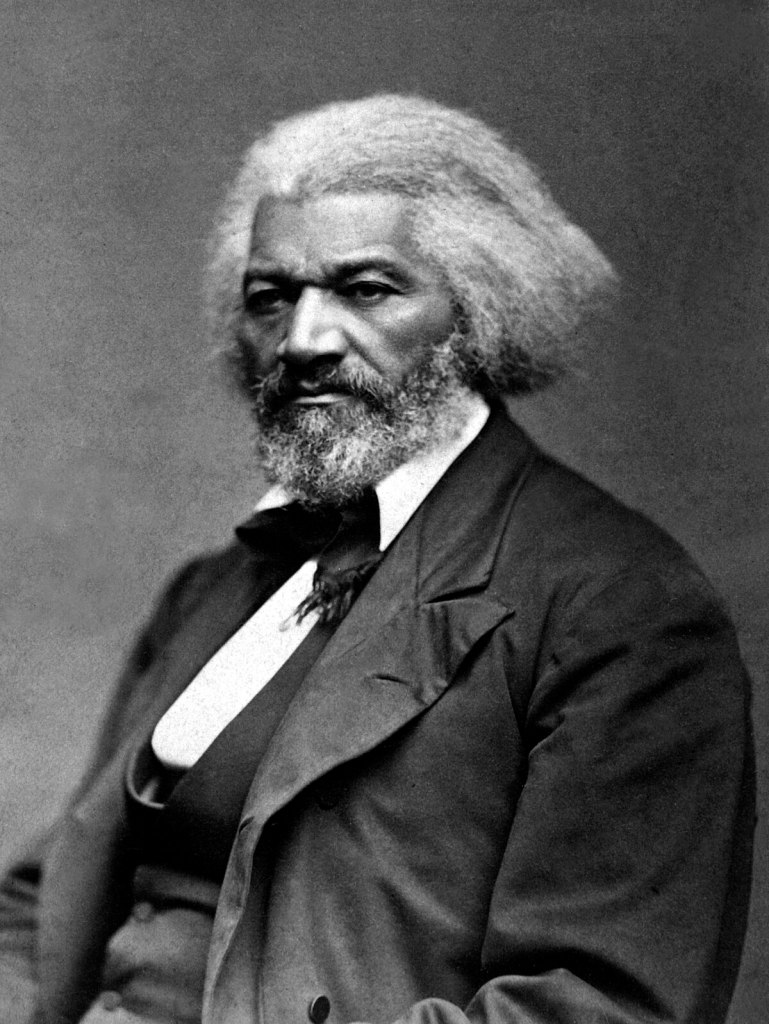

One of my favorite Black writers is Frederick Douglass, who wrote extensively about slavery, race, and the misuse of the Bible to justify oppression. As a formerly enslaved man who became one of the most eloquent and powerful abolitionist voices in American history (and a close friend of President Abraham Lincoln), Douglass directly confronted the false theological justifications for slavery and racial inequality, especially within the American Church. His insights remain profoundly relevant to the topic of slavery and racial separation in Church, society, and marriage.

In the appendix to his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), Douglass drew a sharp distinction between true Christianity and the slaveholding religion of the American South: “Between the Christianity of this land and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference—so wide, that to receive the one as good, pure, and holy, is of necessity to reject the other as bad, corrupt, and wicked.” This powerful statement demolishes the idea that slavery could be supported by genuine Christian faith. Douglass saw the slaveholding church as a corruption of the Gospel—a demonic perversion of Christ’s teaching.

Douglass also directly rebuked those who use Scripture to justify slavery: “The church and the slave prison stand next to each other… Revivals of religion and revivals in the slave-trade go hand in hand.” He exposed the hypocrisy of using Christianity to reinforce racial hierarchies, illustrating how American revivalism often coincided with increased brutality against the enslaved. Douglass’ theological criticism was not anti-Christian—it was deeply Christian in that it called the Church back to the teachings of Christ, particularly love, justice, and dignity for all people. As Luther wrote in his treatise, the Church needed a reformation from The Babylonian Captivity of the Church; similarly, the Church needed a reformation from the white supremacy of the Church.

Douglass affirmed the unity of people in Christ as the Gospel’s true message as well: “I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land.” This quote makes it clear Douglass understood Christianity to be essentially universal (catholic), impartial, and liberating (the freedom of the Gospel—Galatians 5:1). Any church that segregated people based on race or supported slavery was not following Christ but had corrupted His message, in Douglass’ view.

While Douglass did not focus specifically on interracial marriage, his views on racial equality and human dignity laid a clear foundation for it. He believed any division on race was manmade and sinful. In his later writings and speeches, he supported civil rights for all people, including the right to marry freely.

The Lutheran Confessions and the Catholic (Universal) Church

The Lutheran Confessions affirm the Church is not defined by race or geography but by the Gospel. Philip Melanchthon writes, “But the Church is not only the fellowship of outward objects and rites, as other governments, but at its core, it is a fellowship of faith and of the Holy Spirit in hearts” (Ap VII & VIII, 5). As Paul writes similarly, “There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called in one hope of your calling; one Lord, one faith, one baptism; one God and Father of all, who is above all, and through all, and in you all” (Ephesians 4:4-6). These statements make it clear that external distinctions—including race—have no place in defining the Church. Nevertheless, Melanchthon continues in the same paragraph, “this fellowship has outward marks so that it can be recognized.” These marks are not race or ethnicity, but “the pure doctrine of the Gospel and the administration of the Sacraments in accordance with the Gospel. This Church alone is called Christ’s body, which Christ renews, sanctifies, and governs by His Spirit” (emphases mine).

To introduce racial qualifications into Church ecclesiology, fellowship, or leadership is to deny this confessional teaching and, therefore, to create a new religion altogether. It is to build the Church on something other than the Gospel. Such a foundation is not only unstable but heretical. The Confessions insist the marks of the Church are the pure preaching of the Gospel and the right administration of the Sacraments—not ethnicity, culture, or language.

Furthermore,

The distinction between the Law and the Gospel is a particularly brilliant light. It serves the purpose of rightly dividing God’s Word [2 Timothy 2:15] and properly explaining and understanding the Scriptures of the holy prophets and apostles. We must guard this distinction with special care, so that these two doctrines may not be mixed with each other, or a law be made out of the Gospel. When that happens, Christ’s merit is hidden and troubled consciences are robbed of comfort, which they otherwise have in the Holy Gospel when it is preached genuinely and purely. For by the Gospel they can support themselves in their most difficult trials against the Law’s terrors.

FC SD V, 1

Any insistence on racial separation in worship or marriage is a confusion of Law and Gospel. It turns the freedom of the Christian set by the Gospel into bondage once more (Galatians 5:1).

A Call to the Church Today

The Church today must not only reject racism in theory but also in practice. This requires more than occasional statements; it demands intentional discipleship, confession, and even structural reform where any segregation persists. The Body of Christ must be a refuge for the oppressed, not a reinforcement of the world’s divisions.

Repentance means more than apology. It means turning away from sin and toward righteousness. It means examining our liturgies, our institutions, and our relationships. Where barriers exist, they must be torn down by the Gospel. Where wounds remain, they must be bound up. The Church must become what it is: the household of God for every nation (Revelation 7:9).

In a world still riddled with racial hatred, the Church must be a countercultural witness. She must proclaim Christ and that there is neither Black nor White—only the beloved in Christ. She must welcome all people to the font, the Table, and the pulpit, for all have sinned and are redeemed by the same Savior (Romans 3:23-24).

The blood of Jesus does not come in colors. It is not shed for Whites alone, or for Blacks alone, or for any one nation, but for all. “Behold, the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!” (John 1:29). “Not with the blood of goats and calves, but with His own blood He entered the Most Holy Place once for all, having obtained eternal redemption” (Hebrews 9:12). The world for which Jesus died includes every race, every people, every tribe and tongue. Any doctrine or practice that denies this preaches a false gospel.

The Church must be the place where the divisions of this world are undone. At the font, our old identities die and we are made new; at the Table, we are fed as one family. We are one in Christ, not because we’re the same but because He is the same yesterday, today, and forever (Hebrews 13:8).

Let us therefore reject every form of racial superiority—whether Black or White—every wall of separation, and every justification for slavery. Let us be like Paul, “determined not to know anything among you except Jesus Christ and Him crucified” (1 Corinthians 2:2). Let our banner not be “White Lives Matter” or “Black Lives Matter,” but Christ and Him crucified—and in doing so, bear witness to the Kingdom where justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.

Works Cited

Collver, Albert B. III. “Racism and Fellowship.” Logia: A Journal of Lutheran Theology XV, no 2 (Eastertide, 2006).

Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom. New York: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1855.

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845.

King, Martin Luther Jr. Letter from Birmingham Jail, 1963

McCaulley, Esau. Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2020.