Then Eliphaz the Temanite answered… (Job 4:1).

From Compassion to Condemnation

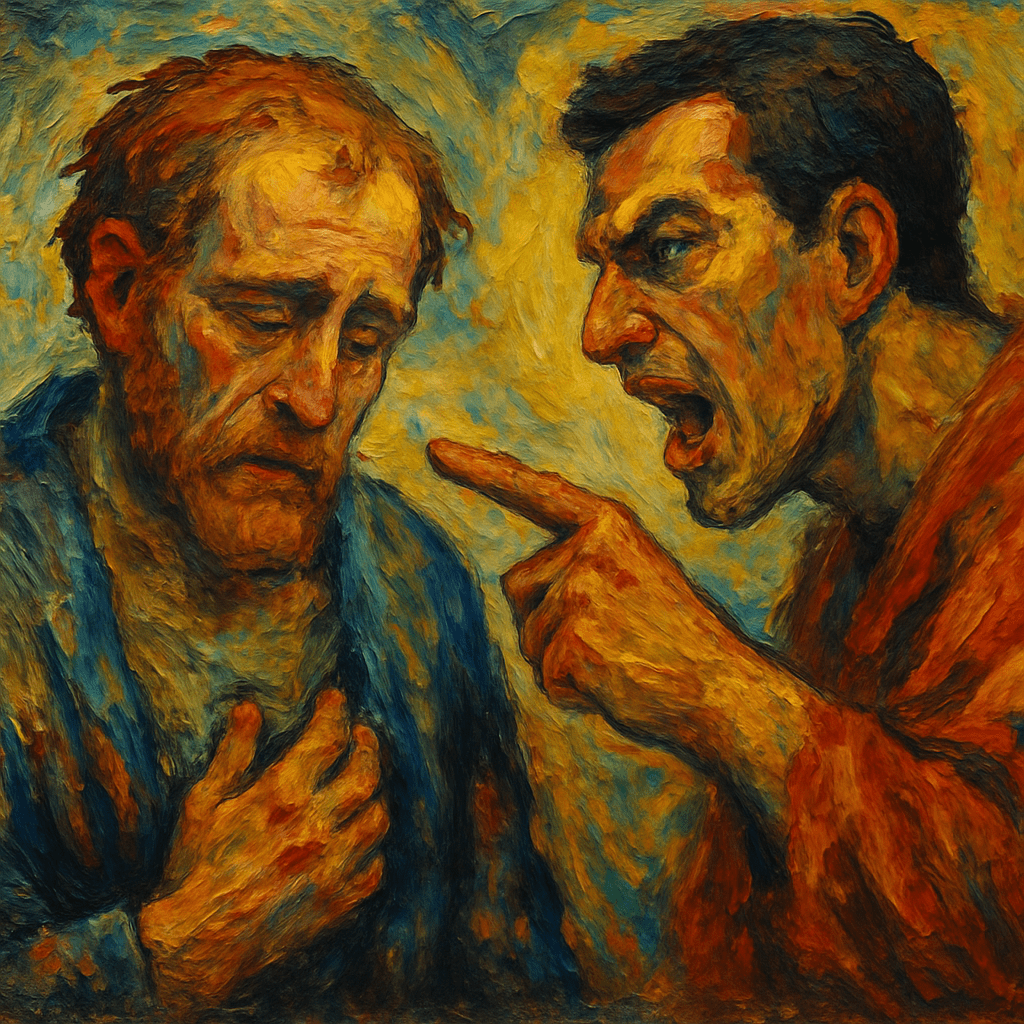

For seven days, Eliphaz and the other friends sat with Job in silent solidarity. Their silent presence was a form of ministry—wordless and reverent. But silence eventually gave way to speech, and with that shift, comfort became confrontation.

Eliphaz begins cautiously, saying, “If one attempts a word with you, will you become weary? But who can withhold himself from speaking?” (v. 2). He appeals to Job’s reputation as comforter of others, reminding him, “Your words have upheld him who was stumbling, and you have strengthened the feeble knees” (v. 4). But his tone quickly pivots. Eliphaz essentially tells Job, “Now that you’re the one suffering, you’re faltering. Shouldn’t you take your own advice?”

At first glance, Eliphaz seems to be offering pastoral care, but he soon reveals the theology driving his assumptions: “Remember now, who ever perished being innocent? Or where were the upright ever cut off?” (v. 7). Eliphaz sees Job’s suffering as evidence of hidden guilt. He insists the innocent do not suffer, and the upright are not destroyed. As a true prosperity gospel heretic, suffering must mean punishment.

If you’ve been wounded by those who meant to help, Job’s experience is perhaps achingly familiar. Eliphaz begins with concern, but it quickly sours into condemnation. This is the pain of betrayal—the moment when someone stops being a friend and acts as both judge and juror. If you’ve ever dared to speak your suffering, only to be silenced by moral analysis or suspicion, know that God sees the injustice of that moment. He does not confuse pious-sounding correction with true compassion. He does not side with those who weaponize theology against the weak.

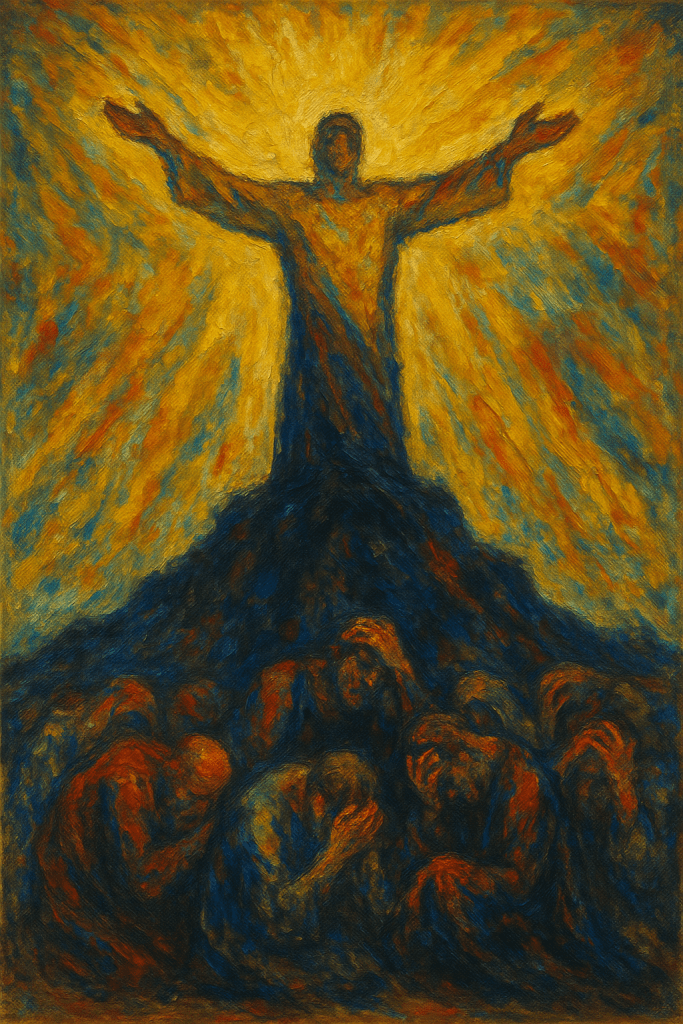

And if you’ve been the one tempted to offer answers instead of presence, let this be an invitation to pause. Our instinct to explain can often be a fear of entering someone’s pain. But Christ does not explain suffering from afar—He enters it. He does not come to those who grieve with doctrine alone, but with tears, touch, and time. True comfort does not demand the sufferer justify their sorrow. It simply stays. The ministry of presence is not silence because of ignorance—it is silence born of love, the kind that refuses to speak when we are meant to weep.

The Theology of Glory and Its Dangers

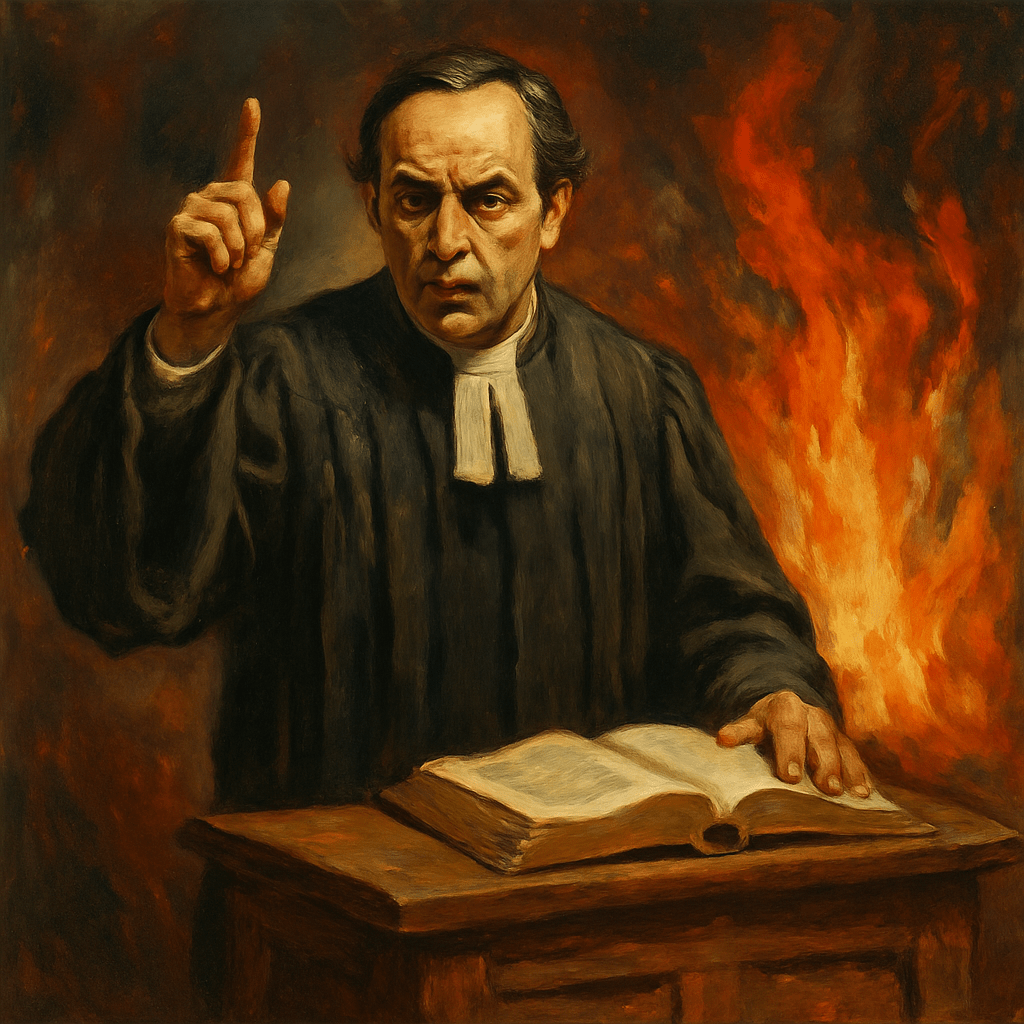

Eliphaz represents what Martin Luther called a “theologian of glory”—someone who interprets God’s will through outward appearances, especially prosperity or pain. In Eliphaz’s framework, righteousness leads to reward, and suffering reveals sin and God’s displeasure. His logic is linear and tidy: God blesses the good and punishes the wicked. Even the Psalms speak this way. Therefore, if Job is suffering, he must have sinned.

But this framework does not account for the righteous sufferer. It cannot comprehend the affliction of a blameless man, nor can it explain the innocent agony of Christ on the cross. It demands all pain must be deserved.

Eliphaz’s voice still echoes in modern Christianity—in every sermon that promises health and wealth to the faithful, in every whisper that says depression must be a spiritual failure, in every theology that cannot leave space for unexplainable pain. This is a theology of merit, not mercy. And although it seems pious, it ultimately undermines the Gospel.

This kind of theology still weighs heavily on the hearts of the suffering. If you’ve been told, directly or indirectly, that your pain is proof of God’s disapproval—or that if you just had more faith or pray harder, your circumstances would improve—then you’ve heard the voice of Eliphaz cloaked in modern language. But the Gospel does not demand we earn God’s favor through ease or emotional stability. Christ does not say, “Come to Me, all who have succeeded.” He says, “Come to Me, all you who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest” (Matthew 11:28). The weary do not need a reason for their pain; they need a Redeemer who meets them in it.

And for those who try to offer care: remember the deepest comfort you can give is not explanation, but presence. The temptation to tidy up someone’s grief with easy answers must be crucified with the old Adam. You do not have to justify God’s actions to be faithful; you simply need to bear witness to His mercy. When the suffering sit in ashes, do not hand them a chart. Sit beside them. Say less. Love more. And when the time does come to speak, speak the cross—where righteousness and suffering met in the flesh of Christ, and where the theology of glory was finally undone.

A Vision Misused

In verses 12-21, Eliphaz recounts a mystical dream or vision. He describes a spirit that passed before his face, bringing a message: “Can a mortal be more righteous than God? Can a man be more pure than his Maker?” (v. 17). The vision highlights the holiness of God and the frailty of humanity—even angels are fallible in Eliphaz’s telling. This message, in itself, is not false. But Eliphaz uses it as ammunition to prove his point: Job must be guilty, and God must be just in afflicting him.

This misuse of spiritual experience—framing it as divine evidence against someone’s character—is spiritual abuse. Instead of lifting Job’s eyes to God’s mercy, Eliphaz throws him deeper into despair by prescribing the Law when Job needed the Gospel. The truth that no one is righteous before God should drive us toward grace, not condemnation. But Eliphaz weaponizes this truth to uphold his neat theology.

From a pastoral perspective, this is a grave error. When the suffering seek comfort, we must not use their pain as proof of guilt. We must never wield theology like a sword against the afflicted. The proper use of God’s truth brings healing, not further harm.

The Law Without the Gospel

Eliphaz applies the Law without the Gospel. He highlights God’s majesty and man’s sinfulness but offers no grace, no promises, and no mention of forgiveness. He has no concept of the righteousness that comes by faith. He does not understand that suffering can coexist with divine favor—that a person can be blameless and broken at the same time.

For pastors, this chapter is a cautionary tale. Eliphaz is not a pagan; he speaks with the vocabulary of God-fearing piety. He invokes divine truth. But his error lies in how he applies it. He sees suffering and concludes guilt without considering God’s ways are often hidden and that His mercy may be working even in the midst of agony.

Lutheran theology insists on properly distinguishing Law and Gospel. The Law reveals sin, but it cannot save. It prepares the heart to receive the Gospel, which alone comforts the broken. Eliphaz knows the Law, but he offers it as the final word. The result is abysmal despair.

Too often, the Church falls into the same patterns. Christians facing chronic illness are told to examine themselves for hidden sin (i.e., the prosperity gospel). Believers struggling with depression are subtly accused of lacking faith. Those who suffer unspeakable loss are offered clichés instead of Christ. Eliphaz’s speech warns us that even well-meaning theology can become cruel when detached from compassion. His words may be sincere, but they are extremely harmful. He claims to defend God but misrepresents Him.

In the end, God will rebuke Eliphaz and say, “You have not spoken of Me what is right, as My servant Job has” (42:7). This judgement should weigh heavily on every preacher and counselor. Right theology must not only be doctrinally sound but also pastorally faithful.

Theology Must Comfort the Broken

Eliphaz begins the long dialogue that will span many chapters, and his assumptions set the tone for Bildad and Zophar. He cannot allow for a suffering saint. He cannot imagine a righteous man in pain. He cannot conceive of grace without merit. But the God who allows Job’s suffering is the same God who later sends His own Son to suffer unjustly. The cross is the answer Eliphaz cannot see. The Church must speak differently. When we see someone in ashes, we do not first explain the ashes—we sit beside them and weep with them (Romans 12:15). We bear witness to the God who entered the ashes Himself. And when we speak, we speak of Christ, the only true comfort in suffering.

2 thoughts on “Job 4: The Voice of the Theologian of Glory”