The third volume in The Stormlight Archive is a novel of collapse and resurrection—an extended meditation on depression, guilt, grief, and the question of whether a person broken by sin can still be called to bear light. For the Christian, especially one shaped by the Lutheran confession of sin and grace, this novel does not merely entertain—it illumines.

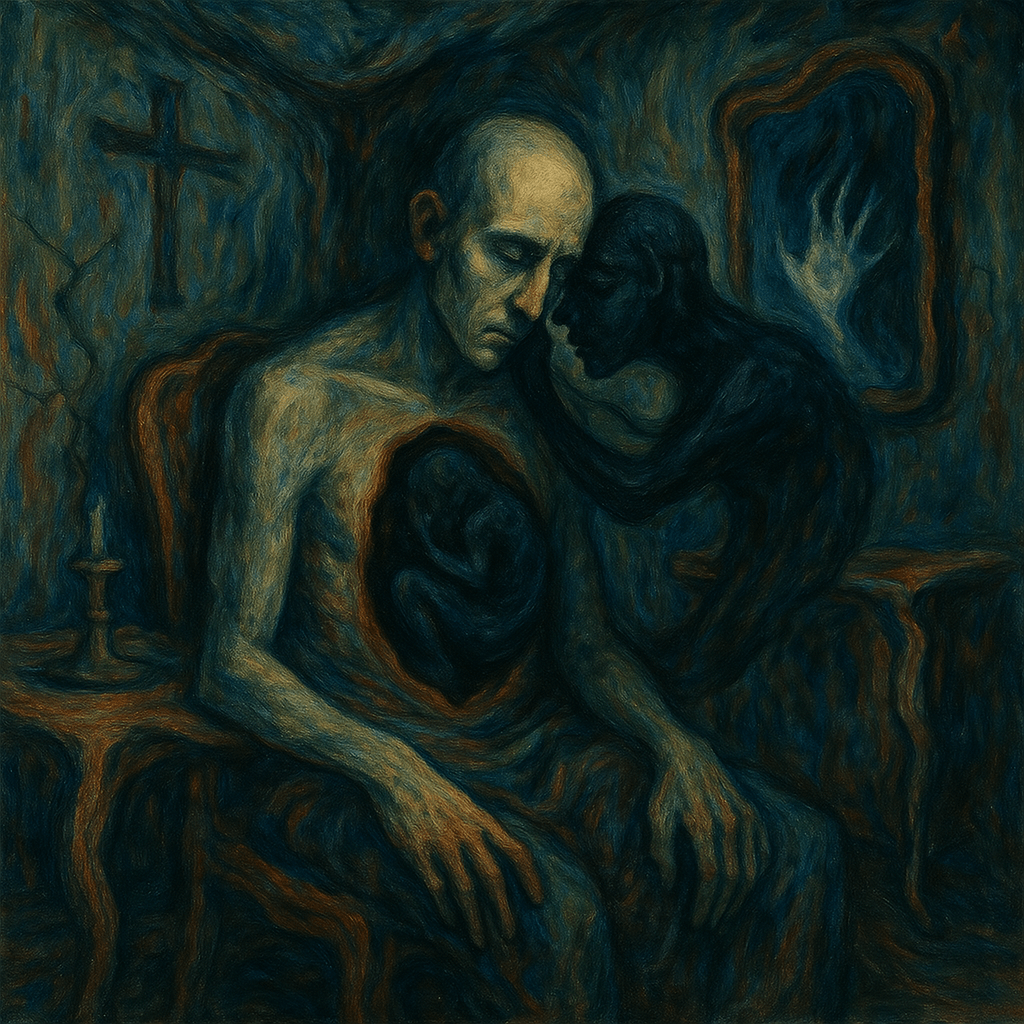

In Oathbringer, Kaladin Stormblessed and Dalinar Kholin descend into the pit of despair—one into a storm of depression, the other into the horror of guilty memory. Yet rather than glorifying their struggles or reducing them to plot points, Sanderson treats mental anguish, moral injury, and self-loathing with profound seriousness and realism. These are not just narrative obstacles; they are soul-deep agonies, handled with a surprising prudence of pastoral care and theological resonance.

This is your spoiler warning.

Kaladin Stormblessed and the Fog of Depression

In Oathbringer, Kaladin’s depression deepens. It is not a temporary sadness but a persistent weight that clouds his judgement, drains his joy, and tempts him to surrender to despair. Sanderson writes, “He wanted to cry, to weep until his breath was gone, but the tears wouldn’t come. He just… sat there. Existing.” I relate to this on a deep level in my own depression. Often, as I experience autistic shutdown alongside this depression, all I can do is sit there and simply exist, the well of my soul too dry to rain any tears.

Kaladin’s depression is not romantic melancholy; it is clinical numbness. Kaladin is not moody—he is in a depressive episode. And Sanderson does not “solve” this with simplistic optimism. Rather, he portrays depression as a condition to be carried, endured, and acknowledged—never shamed.

Luther, too, knew such darkness. In 1527, he wrote, “For more than a week I was close to the gates of death and hell. I trembled in all my members. Christ was wholly lost. I was shaken by desperation and blasphemy of God” (Luther, 85). Luther’s experience of Anfechtung—spiritual assault and despair—matches Kaladin’s storm: an unseen enemy within, whispering lies and silencing hope.

And yet, even amid the storm, Kaladin perseveres. He lifts the wounded, comforts the broken, and refuses to abandon others—even when he feels hollow. In one moment, caring for a dying girl, Kaladin tells her distraught father, “You don’t have to say anything… You don’t have to do anything. Just be there. That’s enough.” These words encapsulate the ministry of presence, which is a practice pastors often utilize when comforting the bereaved—that even just by being present and not saying anything, this is ministry. It’s what Job’s friends should have kept on doing (Job 2:11-13). Kaladin’s perseverance here also mirrors Romans 5:3-5, “we also glory in tribulations, knowing that tribulation produces perseverance; and perseverance, character; and character, hope. Now hope does not disappoint, because the love of God has been poured out in our hearts by the Holy Spirit who was given to us.” Kaladin’s advice to the grieving father is not incidental advice—it is good theology in a hopeless situation.

In Christ, we are not defined by our loss but by the mercy we receive and extend. As Jesus encouraged St. Paul, “My grace is sufficient for you, for My strength is made perfect in weakness” (2 Corinthians 12:9). Kaladin doesn’t overcome depression through grit or glory—he endures it. And that endurance becomes a testimony to every Christian struggling in the shadows. It even encouraged me in my current struggles.

Dalinar Kholin and the Crushing Weight of Guilty Memory

If Kaladin’s arc is about depression, Dolinar’s is about guilt and grief. His descent into memory is one of the most harrowing journeys I’ve ever read. As the Bondsmith, Dalinar is called to unite the world—but he is a man broken by his past, haunted by war crimes he cannot forget and a truth he cannot face.

For two books, Dalinar has wrestled with a memory gap—the blackness surrounding the death of his wife. In Oathbringer, the truth is finally revealed: he accidentally murdered her in a drunken rage and forced a magical forgetting (she was one of the many victims of a city he burned to ashes while she, unbeknownst to him, secretly went to the enemy to beseech their surrender lest they face Dalinar’s merciless wrath). “He’d burned the Rift,” Sanderson writes. “He’d executed a city. Not just the soldiers, but everyone. The women, the children. He’d burned them alive.”

The horror of it unravels him. Dalinar is not a noble man with a few flaws; he is a sinner with innocent blood on his hands. His grief is not exaggerated—it is justified.

And yet, in the novel’s climax, when Dalinar stands before the enemy Odium, the god of hatred, Odium offers him a way out: “Give me your pain,” he tempts like the devil in the wilderness. But Dalinar refuses. Not because he denies his guilt, but because he embraces it: “I will take responsibility for what I have done. If I must fall, I will rise each time a better man.”

This is the Lutheran confessio: not a denial of sin, but its admission before a God who forgives (see Proverbs 28:13; 1 John 1:8-9). Dalinar stands not as a man proud of his virtue but as one who knows the horror of his past and yet does not run from it. His words echo Psalm 51:3, “For I acknowledge my transgressions, and my sin is always before me.” His rejection of Odium is not just triumph—it is repentance. And then, the miracle of grace: a golden light descends, empowered by the Stormfather, and he forces Odium to retreat.

This is not sentimentality, but the Gospel. Dalinar receives not what he deserves but what is freely given by the Stormfather. In Lutheran terms, this is justification by grace through faith (Ephesians 2:8-9). He has no merit to claim, but he received a redemption that is greater than his guilt.

Oaths as Sacrament: Words that Bind

The spiritual climax of Oathbringer hinges on oaths—on the weight of words spoken with meaning. Each Radiant order must speak their Ideals to gain power. But these are not mere incantations—they are confessions. They’re not self-empowering slogans but costly commitments. Kaladin’s Third Ideal (“I will protect even those I hate, so long as it is right”) was spoken in Words of Radiance. In Oathbringer, the burden of such words deepens.

In one moment, Shallan cannot speak her next truth. Adolin, Dalinar’s son, notes: “It’s not about saying it. It’s about meaning it. About accepting it.” This is precisely the Lutheran understanding of the Sacraments. Baptism, for example, is not magic—it is a promise joined to faith (Mark 16:16). As Luther wrote, “For my faith does not make Baptism, but receives it” (LC IV, 53). Confession & Absolution is not merely a ritual but a return to truth—that we are sinners undeserving of God’s grace and forgiveness, yet He freely gives it anyway for the sake of Jesus Christ. And The Lord’s Supper is not a symbol but the actual body and blood of Christ, just as He said (Matthew 26:26-28).

Oaths, in Sanderson’s world, work like sacraments: they bind the speaker to something outside themselves—something extra nos (outside us). And when honored, they reshape the soul.

Light in a Broken World: A Theology of Glory Undone

In the final confrontation of the novel, the ancient enemy known as the Voidbringers return, and the ancient lies begin to unravel. The Parshendi, once seen as monsters, are revealed to be victims. The world’s moral binaries fracture. The revelation is terrifying: “We killed them. We took their minds away. We enslaved them.”

Here, Sanderson pulls the rug out from under every theology of glory. The so-called righteous are exposed as oppressors. The Radiants of old abandoned their oaths because of this terrible realization. The sins of the past haunt the present. But this is not nihilism—it is an invitation to a better faith. Not one built on superiority but on humility.

This resonates deeply with Lutheran theology. The Church is not the gathering of the perfect but the fellowship of forgiven hypocrites. As we confess in the Augsburg Confession, “So that we may obtain this faith [justification by faith in Article IV], the ministry of teaching the Gospel and administering the Sacraments was instituted” (AC V, 1). Faith is not self-created; it is received in the midst of brokenness by the Word and Holy Spirit.

The Truthwatchers and the Theology of Scars

A final theological theme worth highlighting is how Sanderson treats scars—not as symbols of shame but of truth. When Renarin, a misunderstand Truthwatcher (and possibly autistic), reveals he’s bonded to a corrupted spren, others recoil. But Renarin’s visions are real. They show the truth others cannot bear. He says, trembling, “I see… what others will not see. What they cannot see. I see… the cracks.”

In a Church that too often hides brokenness, Oathbringer reminds us it is through our cracks that light gets in. As St. Paul says, “We have this treasure in earthen vessels, that the excellence of the power may be of God and not of us” (2 Corinthians 4:7). Christians are not unscarred—we are wounded healers. And those wounds, rightly confessed, become windows for grace.

A Theology of Oath and Grace

Oathbringer is not merely an epic fantasy; it is a cathedral of broken men and women learning to live under grace. Kaladin’s depression is not cured, but endured. Dalinar’s guilt is not excused, but confessed. And in their wounds, a Radiant light shines—a light that does not deny darkness but overcomes it.

For the Christian, this novel is a mirror. It shows us the pit and the promise. It reminds us oaths matter, confession heals, and grace is not a reward for the worthy but the gift for the penitent. And that “In [Christ] was life, and the life was the light of men. And the light shined in the darkness, and the darkness did not comprehend it” (John 1:4-5).

As Dalinar finally realizes, “The most important step a man can take. It’s not the first one, is it? It’s the next one. Always the next step.” That is sanctification. That is hope. That is the Gospel clothed in Shardplate.

Works Cited

Luther, Maritn. Letters of Spiritual Counsel. Edited by Theodore G. Tappert. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1960.