J.R.R. Tolkien has stubbornly stated that The Lord of the Rings is not an allegory. In fact, he and C.S. Lewis often got into arguments over this subject! Neither is it a theological treatise, of course. And yet, it may be one of the most powerful expressions of Christian truth in modern literature—not because it preaches doctrine, but because it embodies it.

Tolkien, a devout Catholic and close friend of C.S. Lewis, eventually admitted, “The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision” (Tolkien, Letters, 172). Though Lutherans will not follow all his theological emphases, we can affirm this much: the story reveals the deep structure of Christian faith—its view of evil, providence, weakness, sacrifice, and ultimate redemption.

As a Lutheran pastor, I believe every Christian should read Tolkien’s epic. Its scope is vast, yet its moral vision is simple and clear: The lowly are exalted and the proud fall (cf. Luke 1:52), evil consumes itself, and light shines in the darkness (cf. John 1:5), even when it seems the darkness will win.

Let us, then, walk through each volume of the trilogy and see what this work offers to the people of God.

This is your spoiler warning.

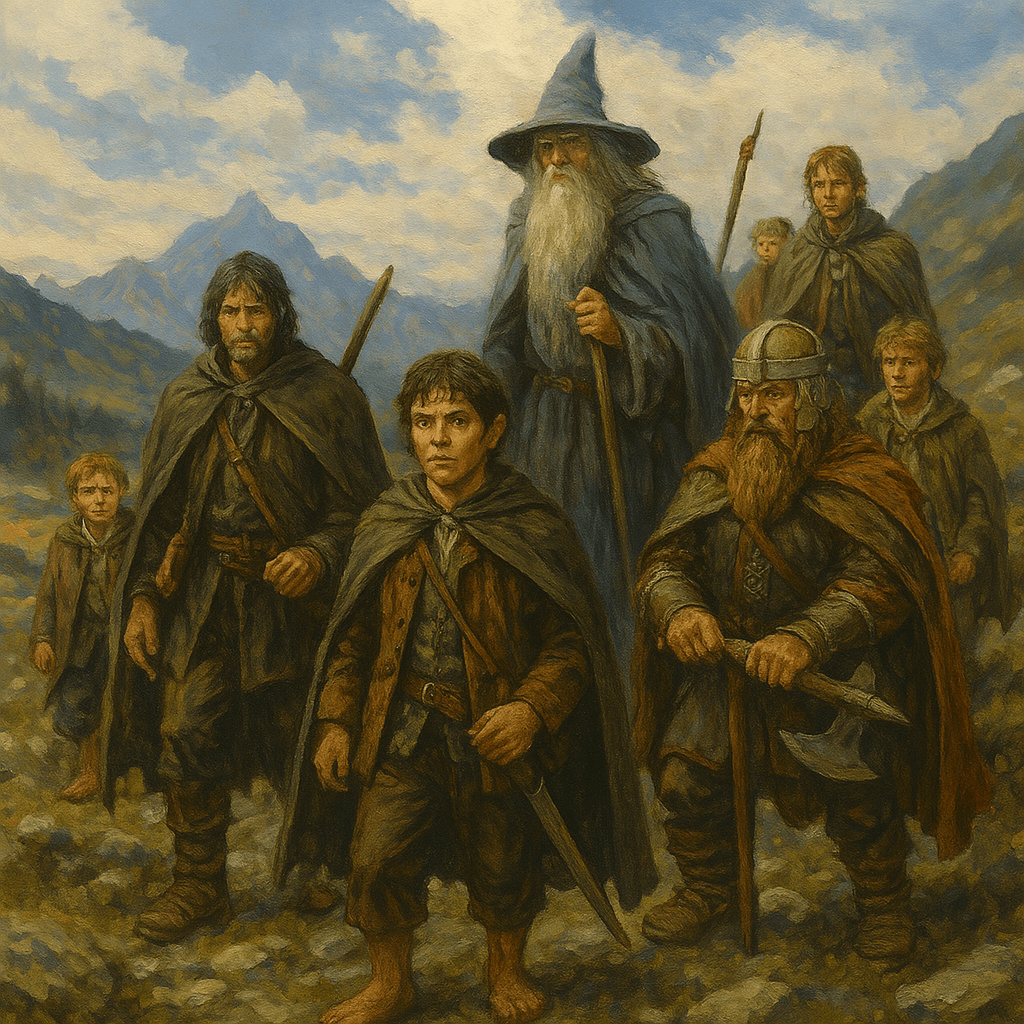

The Fellowship of the Ring: The Weakness that Bears the Burden

Much as the Gospels begin not with a mighty king but a lowly infant in a manger, Tolkien begins not with kings or conquerors, but with hobbits—small, unassuming folk who love gardens and second breakfasts. When the dark power of the One Ring resurfaces, it is not given to the mighty, but to Frodo Baggins, an ordinary hobbit with no ambition for greatness. His calling echoes God’s modus operandi of choosing the lowly for His great purposes. As St. Paul writes, “God has chosen the foolish things of the world to put to shame the wise, and God has chosen the weak things of the world to put to shame the things which are mighty” (1 Corinthians 1:27).

Frodo’s journey begins with a simple act of obedience: taking the Ring away from the Shire. But the moment he steps into the wilderness, the spiritual weight of his task becomes clear. The Ring is not just a burden—it is temptation, a corrupting force that whispers to its bearer, drawing him insidiously toward power and pride.

Gandalf, the wise wizard, refuses to take the Ring, saying: “With that power I should have power too great and terrible… Do not tempt me!” Gandalf understands what Luther called the theology of glory—the temptation to seek God’s work through strength, control, and visible success. Instead, Tolkien uses Frodo to embrace weakness, humility, and the way of the cross.

Tolkien also introduces Aragorn, the hidden king who serves as a humble ranger rather than claiming his throne. His refusal to grasp power too soon echoes Christ’s humility and incarnation, “who, being in the form of God, did not consider it robbery to be equal with God, but made Himself of no reputation, taking the form of a bondservant, and coming in the likeness of men. And being found in appearance as a man, He humbled Himself and became obedient to the point of death, even the death of the cross” (Philippians 2:6-8).

The Fellowship of the Ring ends in fracture: Boromir, noble but proud, tries to take the Ring by force and falls, yet redeems himself as he dies protecting his hobbit companions. The fellowship is scattered. And yet, even here, providence is at work. Frodo presses on not because of his strength, but because of grace working through friendship and faithfulness, which is embodied in Samwise Gamgee.

The Two Towers: The Struggle Against Despair and the Hidden Providence

This volume deepens the theological stakes. As Frodo and Sam journey alone into the darkness of Mordor, the story also follows Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli as they defend the realms of men against the rising tide of evil.

One of the most striking elements in The Two Towers is Tolkien’s portrayal of hope amid despair. The world seems lost. Through Saruman, Sauron has corrupted the forests and twisted nature itself (cf. Romans 8:20-23). Orcs multiply. The kings of men are failing. But Tolkien reminds us that even in the worst places, hope is never absent. As Sam says to Frodo, “There’s some good in this world, Mr. Frodo, and it’s worth fighting for.”

This echoes the Lutheran conviction that God’s work is often hidden under suffering and failure (Deus absconditus). Luther wrote, “God works by contraries so that a man feels himself to be lost in the very moment when he is being saved” (LW 31:57). Luther’s point within his treatise, the Heidelberg Disputation, is that God often hides His grace beneath the very things that seem to destroy us (hence the cross). Sam and Frodo do not feel victorious, but they are being used by providence in ways they cannot yet understand.

We also meet the infamous Gollum more fully in this book. He is both pitiful and treacherous—a picture of sin’s distortion (for a fuller reading of Gollum as a picture of simul iustus et peccator—simultaneously saint and sinner—read this article). And yet, Frodo shows him mercy. When Sam urges caution, Frodo says, “The Quest stands upon the edge of a knife. Stray but a little and it will fail, to the ruin of all… but I do pity him.”

Here is the Gospel tension: justice must be done, but mercy is still possible. Frodo remembers that he, too, could fall to the Ring’s power, so he has mercy on Gollum. Gollum’s presence is a continual reminder that the Ring’s corruption (sin) deforms, but grace can still reach the corrupted.

The volume ends with the battle of Helm’s Deep, a desperate last stand. But even here, salvation comes from unexpected quarters—Gandalf’s return at dawn with reinforcements. It is a picture of Easter victory after long Good Friday suffering. “Look to my coming at first light on the fifth day. At dawn, look to the East.” The eastward direction, I believe, is no accident.

From the early centuries of the Church, Christians have traditionally built their sanctuaries so that the altar faces east—a practice known as ad orientem, meaning “toward the east.” This is not merely architectural; it is deeply theological. The east is the direction of the rising sun, and Christians have long associated it with the resurrection of Christ, who rose “early in the morning” on the first day of the week (Mark 16:2). The physical rising of the sun became a symbol of the Sun of Righteousness who rose from the grave, as prophesied: “But to you who fear My name, the Sun of Righteousness shall arise with healing in His wings” (Malachi 4:2).

Facing east during worship became an expression of hope in the resurrection and expectation of Christ’s return. As Jesus Himself said, “For as the lightning comes from the east and flashes to the west, so also will the coming of the Son of Man be” (Matthew 24:27). Thus, worshipers orient themselves—liturgically and spiritually—toward the direction of Christ’s advent and eternal morning.

While Gandalf’s coming from the east may not be allegory, it is rich with Christian meaning. Light breaks in the east, and the sun rises. Resurrection will cross the proverbial horizon.

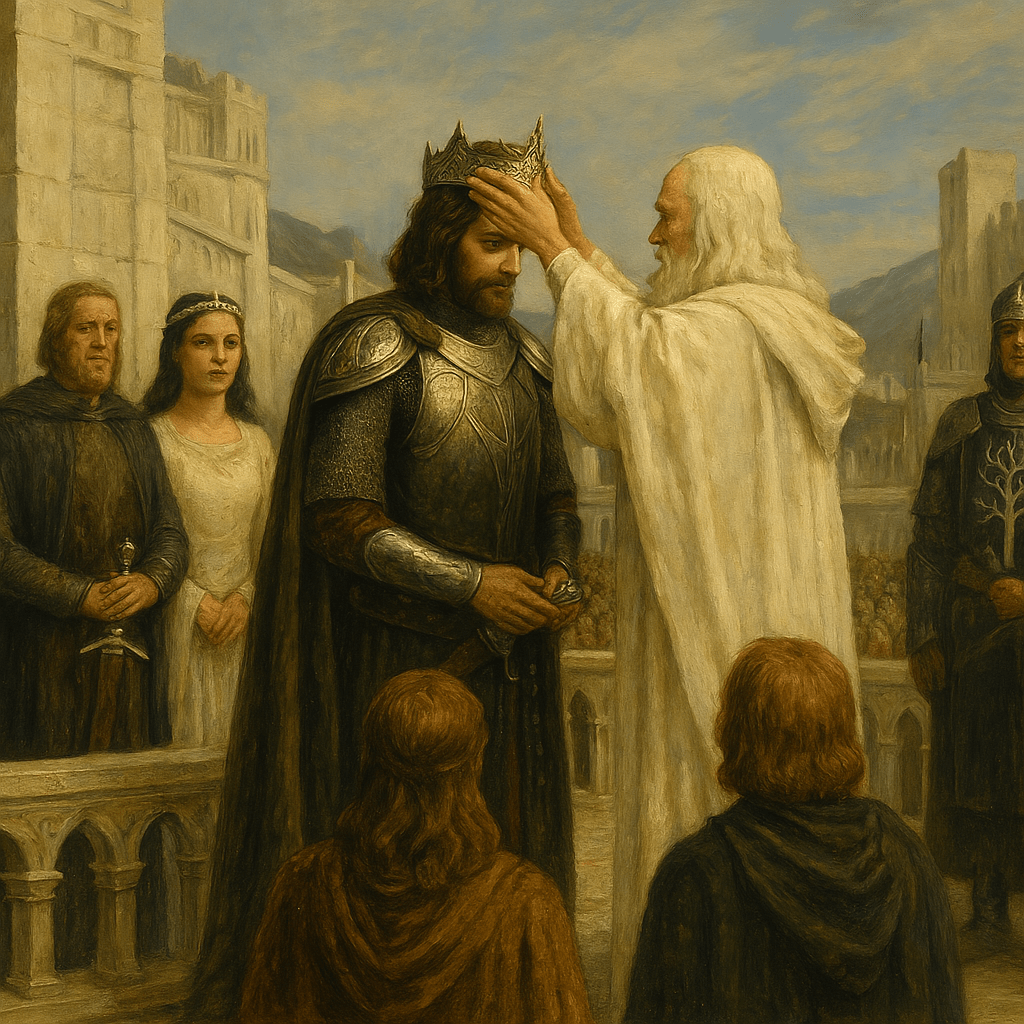

The Return of the King: The Triumph of Humility and the Healing of the World

The final volume is the most explicitly Christological. Aragorn claims his kingship not through conquest, but by entering the Paths of the Dead—a descent into shadow and death itself (which was, indeed, prophetical). Only through this can he bring life and victory.

He is a clear echo of the Christus Victor model of the atonement: Christ descends into Death and Hell and rises victorious, leading the captives free. As Tolkien writes in the novel, “The hands of the king are the hands of a healer, and so shall the rightful king be known.” Indeed, Aragorn literally gains powers of healing, and uses it to save Faramir from near death (which they frustratingly don’t show in the 2003 film adaptation). This quote echoes Isaiah’s messianic prophecy: “Surely He has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows… and by His stripes we are healed” (Isaiah 53:4-5).

Meanwhile, Frodo and Sam approach Mount Doom. Frodo is now utterly exhausted—his spirit crushed, his strength gone. Sam must carry him, saying, “I can’t carry it for you, but I can carry you.” This moment of vicarious love is perhaps the most Gospel-rich passage in the trilogy. Many Christian readers argue Sam represents Christ here, but I’m of the opinion that he actually represents Simon of Cyrene (Luke 23:26). Just as this African man helped Christ bear His cross for a little while, so Sam helped Frodo bear his cross—the One Ring—for a time. And just as it was still up to Christ to bear His cross to the end, so Sam eventually had to put down Frodo for him to bear the Ring to the end.

The moment also reflects the Christian vocation of bearing one another’s burdens (Galatians 6:2), where we, too, become a Simon of Cyrene for somebody by helping them bear their cross for a little while. Fans of LOTR like to say everyone needs a Sam. Even more, everyone needs a Simon. Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer, in writing about the “ministry of bearing,” expertly delineates this in his book, Life Together:

[The Christian] must suffer and endure the brother. It is only when he is a burden that another person is really a brother and not merely an object to be manipulated. The burden of men was so heavy for God Himself that He had to endure the Cross… But He bore them as a mother carries her child, as a shepherd enfolds the lost lamb that has been found… In bearing with men God maintained fellowship with them. It is the law of Christ that was fulfilled in the Cross. And Christians must share in this law… what is more important, now that the law of Christ has been fulfilled, they can bear with their brethren.

pp. 100-101

But at the end, Frodo fails—he claims the Ring for himself. But Gollum, in his final act of madness, takes the Ring, and falls into the fire with it. Evil destroys itself, just as David prays in Psalm 57:6, “They have prepared a net for my steps; my soul is bowed down; they have dug a pit before me; into the midst of it they themselves have fallen.” The quest to destroy the Ring succeeds, not through strength, but through mercy, weakness, and providence.

Yet Frodo cannot return to normal life. He is too wounded—his soul has become too broken by the weight of the One Ring. Thus, he sails west to the Undying Lands, Valinor—a vision of Heaven. This isn’t because he earned it; it’s because his suffering has made him so broken that he can no longer live in the Shire. And Sam, grounded and faithful, returns to live out his days in peace. His final words are simple: “Well, I’m back.”

The Eucatastrophe and the Christian Imagination

Tolkien coined the term eucatastrophe (a wordplay on Eucharist) to describe the sudden, unexpected turn toward good in the face of overwhelming evil. He wrote, “It is the sudden happy turn in a story which pierces you with a joy that brings tears… a glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief” (On Fairy Stories, in Tree and Leaf, 68). This is the Christian story. It is the resurrection.

The Lord of the Rings compels Christians to see the world sacramentally—to recognize that weakness is strength, that humility is victory, that light shines in the darkness, and that joy is coming. It does not preach; it embodies the cross-shaped pattern of history.

Further, it teaches us to resist evil—not by power, but by pity.

It teaches us to persevere—not by triumph, but by faith.

And it teaches us that in the end, the King will return.

Works Cited

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Life Together. Translated by John W. Doberstein. New York: HarperOne, 1954.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Edited by Humphrey Carpenter. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

Tolkien, J.R.R. Tree and Leaf: Including the Poem Mythopoeia. London: HarperCollins, 2001.