The Hyperion Cantos by Dan Simmons is one of my favorite—if not the favorite—series I’ve ever read. It is a four-book science fiction epic spanning centuries, species, and galaxies. It’s not overtly Christian in the way one might expect. Its universe includes artificial intelligences, post-human consciousness, fallen worlds, and brutal violence—a masterful fusion of sci-fi, horror, romance, and fantasy. It blends literary allusion with high-concept futurism, but underneath its dense narrative structure and speculative theology lies a surprising and deeply moving reflection on many of the Christian faith’s most vital themes: suffering and sacrifice, incarnation and resurrection, providence and mystery, and the tension between Law and Gospel.

Though Simmons himself does not write from a confessional Lutheran (or Christian) standpoint, The Hyperion Cantos—particularly the first two novels (Hyperion and The Fall of Hyperion)—demands the attention of every Christian reader willing to think theologically and imaginatively. For the Lutheran in particular, who holds the paradox of the cross and the hiddenness of God at the center of their faith, these books are not only provocative—they are profoundly illuminating.

This is your spoiler warning.

Genre, Structure, and the Theological Imagination

The Hyperion Cantos begins as a futuristic Canterbury Tales—seven pilgrims journey to a mystery world called Hyperion, each telling their story along the way. Each story explores themes of grief, justice, memory, love, devotion, and sacrifice. These pilgrims are not stereotypes; they are richly drawn images of humanity in extremis, clinging to meaning in a universe that seems increasingly mechanistic and cruel.

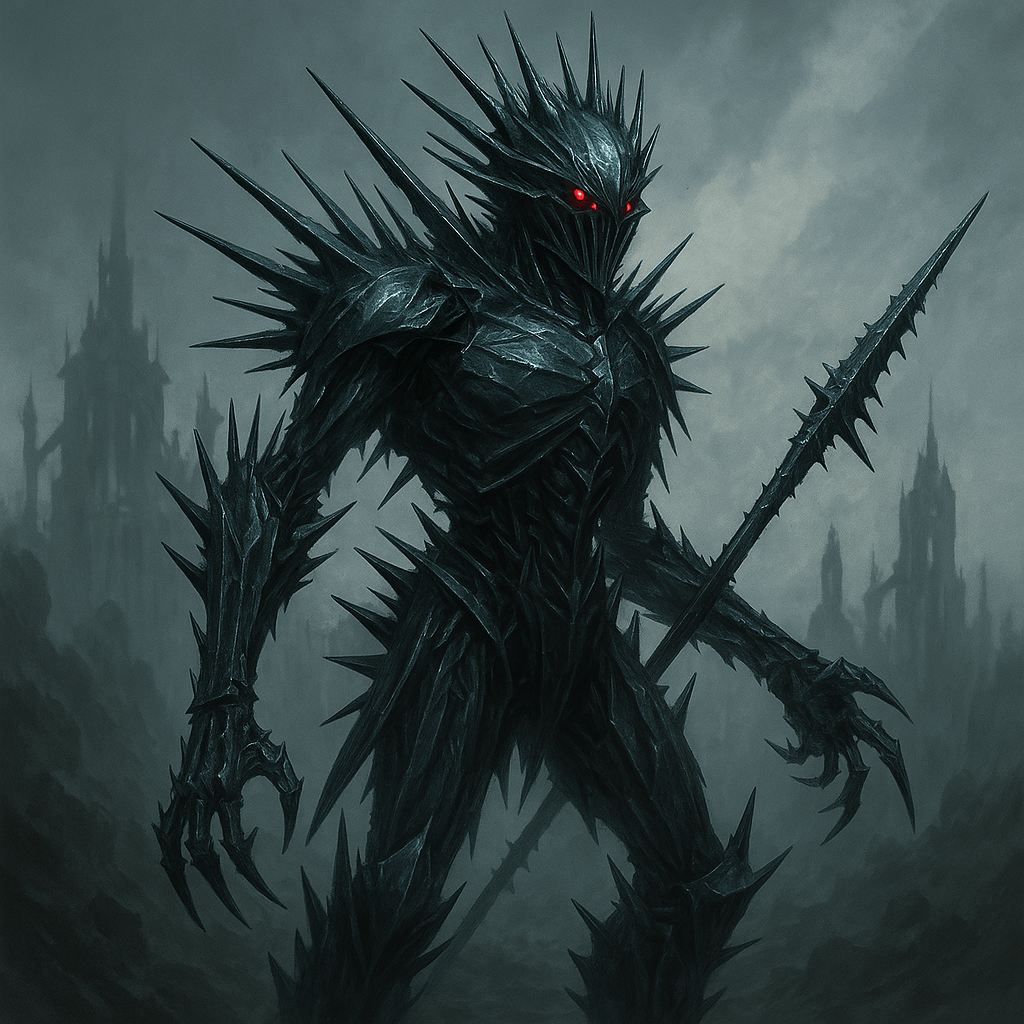

The central mystery of the series revolves around the Shrike—a terrifying, metallic being that inhabits the Time Tombs of Hyperion. The Shrike is worshipped by some, feared by most, and seems to move freely through time and space. It kills indiscriminately—or so it seems. As the narrative progresses, the Shrike comes to represent divine judgement, but also divine paradox. It is, at various points, a destroyer, a redeemer, a reflection of humanity’s violence, and an agent of something greater than itself.

This is precisely where Christian theology must enter, not to explain the Shrike, but to recognize in it the literary shadow of the Deus absconditus—the hidden God who appears most terrifying in His judgements and most merciful in His wounds.

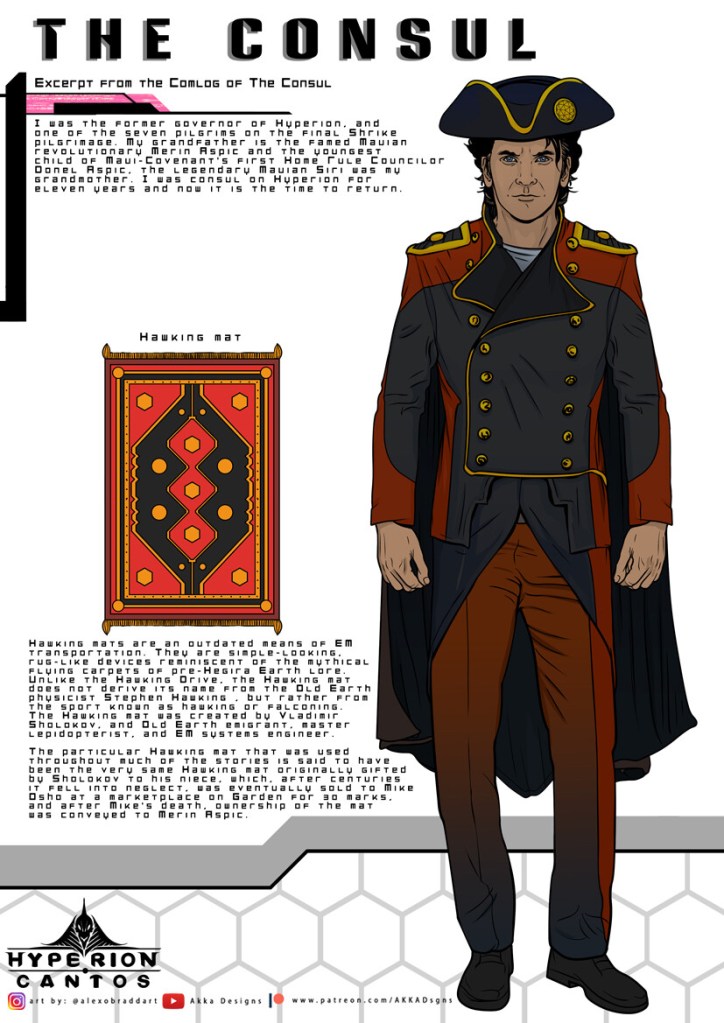

The Consul: Betrayal, Memory, and the Judgement of History

The Consul—the final narrator of the seven pilgrims in Hyperion—is a man defined by dual allegiances and long memory. As a descendant of the Hegemony’s colonizers and the leader of a long-planned rebellion against that very system, he stands at the crossroads of history, heritage, and judgement. His pilgrimage is not one of curiosity or desperation, but penance.

In the Consul, Christian readers may see a complex reflection of Pontius Pilate—a man caught between competing powers, aware of the weight of truth but unable (or unwilling) to act decisively in its favor until the cost is irreversible. His betrayal of the Hegemony is not done for gain, but in a kind of moral exhaustion—a belated reckoning with the sins of his forebears and the suffering of the oppressed.

From a Lutheran perspective, the Consul becomes a figure of the burdened conscience. He does not seek justification; he believes it is impossible for him. His mission is an act of attrition, not redemption. He carries the memory of an indigenous lover long dead, of a grandfather’s failed rebellion, and of a thousand silences where he might have spoken justice but did not.

This is the man under the Law—aware of sin, bound by guilt, haunted by memory. And yet, his participation in the pilgrimage and his willingness to walk alongside the others rather than above them marks the first movement toward contrition, or confession. He is not righteous, but he is no longer self-deceived.

The Consul reminds Christians that history is not a clean record, that guilt is inherited (not in terms of responsibility but in terms of damnation, i.e., original sin), and that the path to grace begins not in denial but in truth—not in attrition, but in contrition.

Brawne Lamia: Incarnation, Death, and the Word Made Flesh

If the Consul represents the memory of judgement, Brawne Lamia—the private investigator turned mother of a messianic child—embodies incarnation. Her story arc, especially in The Fall of Hyperion and Endymion, draws unmistakably from Christian theology: she conceives a child by a being who transcends time, carries that child under threat of death, and gives birth to Aenea, the Christ-like figure of the Cantos (she is covered below).

What makes Lamia’s story theologically powerful is not only the parallels to Mary, the Mother of God, but also the way it explores the cost of bearing the Word. Brawne is not meek or submissive—she is skeptical, strong-willed, and fiercely independent (hence the wordplay of her first name). And yet, she accepts a calling that defies understanding. Her life becomes the vessel through which the divine mystery enters history.

As Lutherans, we affirm that Mary is Theotokos—God-bearer, the Mother of God—not because she understood what she was doing, but because she believed the promise. In this way, Lamia also becomes a theotokos of sorts—not of divinity, per se, but of the one who will deliver (through childbirth) truth to a dying cosmos. And like Mary, Lamia must suffer: she faces rejection, persecution, and ultimately death.

But her death is not meaningless; it is sacrificial and maternal, an echo of the cross in the life of the one who gives all for the life of the world. Lamia reminds the Christian that vocation is not always about survival but faithfulness, even unto death. Her courage is not her own; it is given, shaped by love, and fulfilled in service.

In her, the reader sees that the Incarnation is not a safe doctrine. It enters violently through the world—the pain of childbirth, His Passion, and crucifixion, bearing hope and death together. And those who bear it will suffer. But in their suffering, they testify to the One who has already come and who still comes.

Martin Silenus and the Corruption of Glory

Among the seven pilgrims in Hyperion, Martin Silenus—the aging, foul-mouthed poet—seems the least likely candidate for theological reflection. He is obscene, egotistical, sexually debased, and often drunk. But beneath his grotesque exterior lies a surprisingly deeply Lutheran theme: the futility of the theology of glory.

Silenus embodies what Luther in his Heidelberg Disputation calls the theologian of glory—the one who seeks God (or immortality, or meaning) through personal greatness, aesthetic achievement, and strength. Silenus does not worship the divine; he worships art. He believes suffering is a tool to create beauty, that madness is justified if it yields poetry, and that the human will can justify itself through the sublime.

“God was not in the thunder,” Silenus says, “but in the poem I wrote about it.” Even more striking, he also says, “You see, in the beginning was the Word. And the Word was made flesh in the weave of the human universe. And only the poet can expand the universe.” These are the purest expressions of humanism elevated to idolatry.

But Silenus is not merely an egotist; he is also haunted. He knows his finest work came not from his own talent, but from proximity to the Shrike and the madness it brought. He literally calls it as his Muse. He refers to his magnum opus, The Hyperion Cantos, as a prophecy he does not understand—something being written through him, not by him. He is the vessel of something he both fears and longs for.

From a Lutheran view, this also mirrors the paradox of vocation and sin. God often works through broken instruments—not because of their greatness, but in spite of it. Silenus’ poetry becomes profound not because he commands it, but because he is undone. His glory is shown to be hollow. His masterpiece is not a triumph, but a cry of desperation.

And yet, this is where the Gospel can speak. As Luther writes, “It is certain that man must utterly despair of his own ability before he is prepared to receive the grace of Christ” (LW 31:40). Martin Silenus is never fully redeemed in the pages of the Cantos, but he is stripped. The façade falls. And in that humiliation, the reader sees something more true than all his poetry: a man who has run to the ends of art, sex, and fame—and found them empty.

He is, in the end, what we all are without Christ: a sinner whose glory cannot save.

The Cruciform Narrative: Rachel and the Theology of the Cross

Among the most heartbreaking and spiritually resonant stories is that of Sol Weintraub, a Jewish scholar whose daughter Rachel contracts a mysterious condition that causes her to age in reverse. Each day, she forgets more. Each morning, she awakens with less memory of her life, her studies, and her family. Sol’s pilgrimage is not for his own sake, but for hers. He seeks the Shrike not to escape death, but to find healing—or at least justice—for the child he loves and who no longer knows him.

Lutherans will see in Sol the image of Abraham, of course (Simmons makes this explicit), but also of God the Father, who watches His Son bear suffering not as punishment, but as the redemptive mission. More than that, Rachel becomes a type of Christ—her condition, though not caused by her own fault, is the means by which she reveals both her father’s faith and the world’s need for grace.

In the end, Sol offers her to the Shrike not as a human sacrifice, but as a desperate act of trust, just as Abraham does. And Rachel is taken, but not destroyed. She is preserved beyond time. The reader is not told exactly what this means (until the sequels), only that it is not the end. For the Christian, this moment reads like a veiled image of the resurrection—the promise that what is given to God in agony is never lost. As Luther writes, “He deserves to be called a theologian, however, who comprehends the visible and manifest things of God seen through suffering and the cross” (LW 31:40). In other words, faith is not knowing how the story ends; faith is trusting the One who writes it.

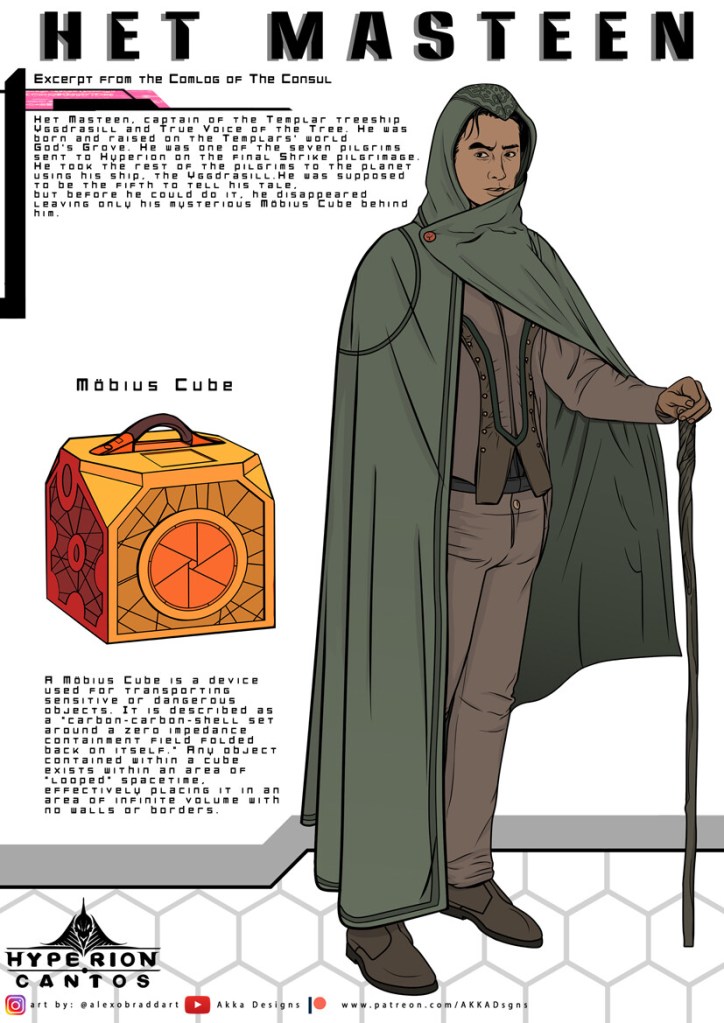

The Church and the Cross: Father Hoyt and Het Masteen

Christianity appears in the Cantos not merely as a cultural relic but as a living tradition with real theological weight. This is most evident in the characters Father Paul Duré and his eventual vessel, Father Lenar Hoyt. Duré is martyred, then resurrected—repeatedly—through a parasitic cruciform device that grants immortality at the cost of endless suffering. This image is grotesque but also narratively brilliant.

The cruciform is not merely a symbol; it is a burden. The resurrection it gives is not freedom, but torment. Duré dies and rises again, over and over, bearing the agony of Golgotha without its hope. Some might read this as blasphemy, but I read it as Good Friday.

The false cross—offering life without grace—is the Law in its purest, most damning form. The true cross—the cross of Jesus—offers death that brings life. Simmons does not resolve this tension, unfortunately, but he does place it at the center of the story. Christians reading this arc must ask: What is the cross I bear? Is it mine, or Christ’s? Am I crucified with Him (baptized), or merely by the world? (See Romans 6:3-6; Galatians 2:20.) This contrast between the cruciform device and Christ’s cross becomes a crucial lens through which the Christian reader can discern truth from parody.

But Hyperion also gives us a quieter, more mysterious religious figure in Het Masteen, the Templar. He is the least vocal of the pilgrims—a steward of the forests and ancient, Earth-like traditions of spiritual balance. His presence evokes the role of monastics and caretakers of creation in the Christian tradition—those who witness not by words but by faithful stewardship and silent strength. Though he disappears partway through the story (only to re-emerge later in bizarre and ambiguous ways), Het Masteen serves as a symbol of the hidden Church: the one that prays when no one sees, the one that tends the garden in exile, the one that bears witness by being rooted in the old and true things.

Masteen reminds us that not every spiritual voice must be loud. Some simply remain faithful. And in that, he echoes the vocation of countless unnamed saints—those who do not lead armies or write theology, but who, like monks of old, guard the sacred spaces in a world that is forgetting them.

Artificial Intelligence, Babel, and the Hidden God

Another theme that pulses through The Hyperion Cantos is the Tower of Babel revisited. The AIs known as the TechnoCore seek to become gods. They desire omniscience and omnipresence, even seeking to create a synthetic messiah in defiance of the “promised” messiah, Aenea.

In Endymion and The Rise of Endymion (the 3rd and 4th books respectively), Aenea becomes a Christ-like figure, preaching love, communion, and the rejection of fear (drawing mostly from Eastern philosophy, unfortunately, but the Christian themes are still present). Her teachings awaken hearts but also incite persecution. She walks among the people, heals, teaches, and finally dies—only to transcend death in a way that offers hope to the cosmos.

Simmons does not perfectly replicate the Gospel here, but he does reflect its shape. Aenea is not Jesus, but she is a narrative icon—a pointer to Him. Her story shows salvation is not found in domination but in incarnation—not in force, but in presence.

In Lutheran terms, Simmons gives us a world where the theology of glory (the TechnoCore’s vision of power, immortality, and godhood) collides with the theology of the cross (Aenea’s suffering, death, and witness). The reader is left to decide which truly redeems. To draw from Luther again, “A theologian of glory calls evil good and good evil. A theologian of the cross calls the thing what it actually is” (LW 31:40-41). If you want to be wise, become a fool, and look to the cross.

Sacrament and Resurrection: The Final Vision

The final chapters of The Rise of Endymion are among the most spiritually arresting in all of science fiction. Aenea’s death is not the end. She becomes, in a mysterious way, present with her followers—not just in memory, but in something very similar to the Real Presence confessed in Lutheran Eucharistic theology.

She offers her blood as a gift. She enters into those who follow her. And through her, they begin to be changed—not merely biologically, but spiritually. They experience empathy, unity, courage, and hope. Evil does not vanish, but it does lose its sting (cf. 1 Corinthians 15:55-56).

This is, for the Christian, a powerful (if imperfect) image of the Sacrament of the Altar, where Christ gives us His true body and blood for the forgiveness of sins, life, and salvation. What Simmons gives us is a sacrament without the name, but still resonant with real meaning. It’s not orthodoxy, but it is a yearning for it.

Why Christians Should Read The Hyperion Cantos

- It confronts the question of suffering. Simmons does not give easy answers, but he places suffering at the heart of the story, just as the cross is at the heart of the Christian life, though it is not an easy (or satisfying) answer.

- It explores the cost of love. Every major character is transformed by sacrificial love. This is not sentimental, but theological.

- It critiques false religion and honors true faith. The Hyperion Cantos exposes the dangers of power-hungry institutions but elevates humble, faithful service (through the corrupt state of the Catholic Church in the universe he writes).

- It honors mystery. Simmons does not try to explain everything. Like Job, he sits before the whirlwind (Job 38:1). Christians, too, are called to worship God who is both revealed and hidden; and we do not try to explain the miracle of the Sacraments (which is why we reject both transubstantiation and consubstantiation).

- It imagines a cosmos where grace still breaks in. Even in the far future, even in the darkest places, the image of Christ—wounded, risen, returning—still heals.

Christ Beyond the Void

Dan Simmons’ The Hyperion Cantos is not a catechism or a Christian allegory, but it is a profound work of theological imagination—one that explores the depths of human sin, the mystery of divine providence, and the hope of resurrection that changes everything. For Christians willing to wrestle, to discern, and to hope, these books are a treasure. They do not preach the Gospel, but they do prepare the soul for it.

Because even among the stars, the cry of the cross echoes. And even in the farthest future, the blood of Christ speaks a better Word.