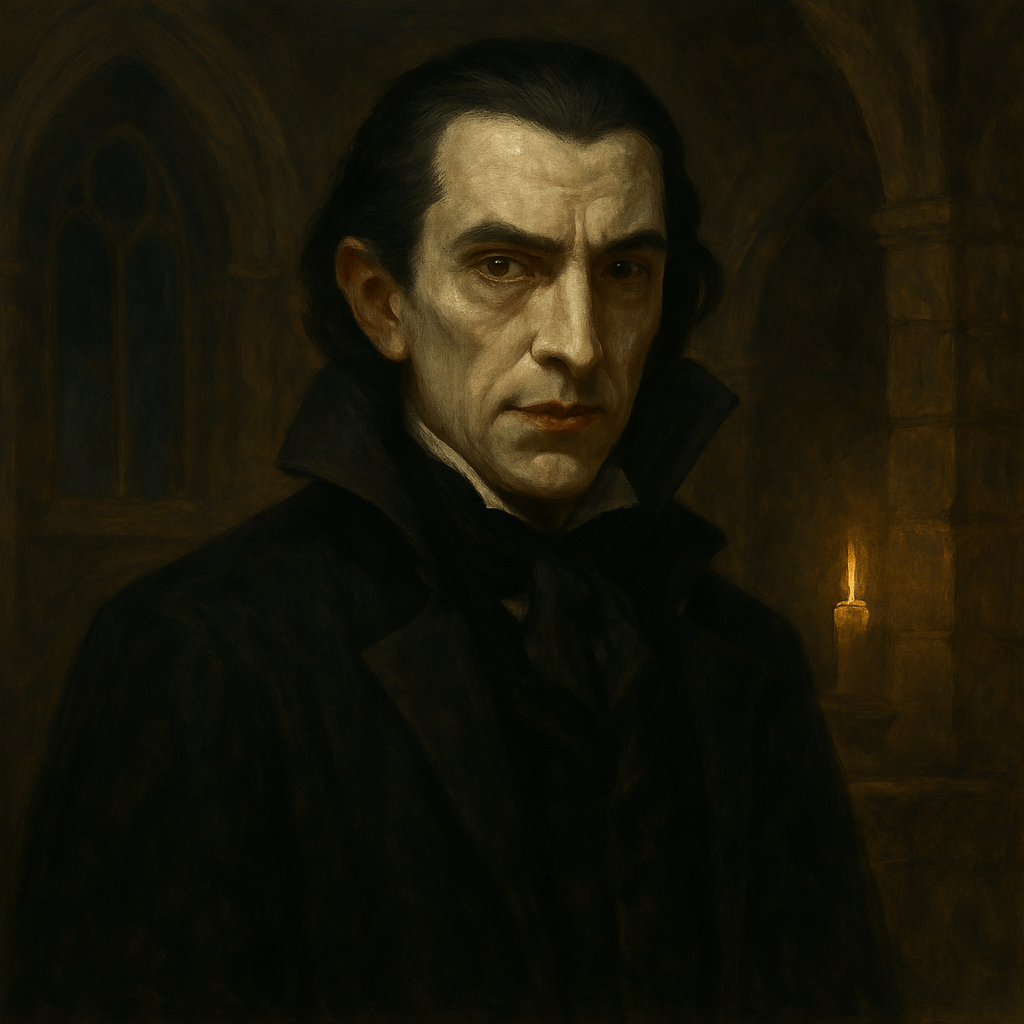

In the modern imagination, Dracula is often reduced to a gothic cliché—caped vampires, blood-soaked romance, or campy horror. Worse still, many people’s only exposure to Stoker’s original 1897 novel is through the 1992 film Bram Stoker’s Dracula, directed by Francis Ford Coppola—a lush but deeply misguided adaptation that drowns theological clarity in erotic sensationalism. The film does not honor the novel, but corrupts it, relegating the classic to cheap soft porn. Stoker’s Dracula is not an erotic romance; it is a spiritual warfare narrative where evil is real, seductive, and parasitic, and where holiness, courage, and the Word of God are the weapons by which it is defeated.

Dracula is not only worth reading, I would even call it an essential read for Christians. It confronts the Christian reader with the true nature of evil: not as a mere philosophical abstraction or psychological disturbance, but as a personal and malignant force that seeks to devour life and desecrate the sacred. And more than that, it shows evil is defeated not by ingenuity or power, but by the humble, consistent application of the Word and Sacraments.

This is your spoiler warning.

The Reality of Evil: Not Gothic, But Biblical

The modern world has domesticated evil. It is explained away by trauma, reduced to pathology, repackaged as anti-heroism, and even utilized for entertainment purposes in occult things like Ouija boards. But in Dracula, evil is spiritual and personal. Count Dracula is not misunderstood or a tragic lover; he is a predator—a demonic parasite who feeds not only on blood but also on fear, shame, and spiritual weakness (which is something the recent 2024 re-adaptation, Nosferatu, gets right, directed by Robert Eggers).

Stoker’s Dracula is a figure of satanic deception. He is ancient, cunning, and powerful, but always dependent. He has no life in himself; he must drink blood to live, manipulate others to gain access, and flee at the sight of holy things. In this, he mirrors what the Scriptures say about the devil: “Your adversary the devil walks about like a roaring lion, seeking whom he may devour” (1 Peter 5:8).

What makes Dracula distinctively Christian is that it does not fight evil on neutral terms or pretend science and reason alone can defeat this darkness. As Dr. Van Helsing comments, “Ah, it is the fault of our science that wants to explain it all; and if it explain not, then it says there is nothing to explain.” Every major victory in the novel comes through explicitly Christian means: the reading of Scripture, the power of prayer, the use of the Host from the Eucharist, and crucifixes. Evil is not overcome by science or silver bullets; it is overcome by Christ crucified.

The Holy and the Profane: A Theology of Blood

At the heart of Dracula is a perverse inversion of the vital role blood plays in Christian soteriology. Scripture says life is in the blood, which God provides for the Israelites to make atonement for their souls (Leviticus 17:11), which is a stark foreshadow of the atonement Christ gives by shedding His blood on the altar of Mt. Calvary (Matthew 26:28; 1 Corinthians 5:7; 15:3). And in the Sacrament of the Altar, Christ gives His very body and blood to His Church for the forgiveness of sins, life, and salvation, as He Himself says (Matthew 26:28).

Dracula mocks this. He turns blood from a gift into a theft. He forces himself upon others not to give life, but to steal it. His feeding is not communion, but violation. He leaves his victims frail, ashamed, confused, violated, and spiritually drained. Lucy Westenra, who becomes his victim, is not seduced but ravaged, and her descent into undeath is portrayed as a grotesque parody of resurrection. Whereas Christ gives His life to save, Dracula takes life to preserve himself.

This is why the 1992 film adaptation is such a profound betrayal of the novel’s theological core. By turning Dracula into a tragic, romantic anti-hero (which the 2024 Nosferatu also unfortunately does) and rendering his interactions with Lucy and Mina as erotically charged seductions, Coppola’s film removes the moral clarity of its source material. It blurs the line between love and lust, between evil and brokenness, and ultimately reimagines violation as desire.

Stoker, by contrast, draws the line boldly. Dracula is evil. What he does is evil. And the response is not moral confusion, but righteous resistance grounded in Christian faith.

The Communion of Saints and the Power of Christian Fellowship

Another deeply Christian element of Dracula is the portrayal of the fellowship of believers. The fight against the mighty vampire is not waged by a lone hero, but by a community—men and women who love one another, pray together, share knowledge, confess weakness, and hold each other accountable.

This is a beautiful picture of the Church Militant. Van Helsing, the Catholic professor, quotes Scripture and insists on the use of sacred objects. Jonathan Harker, after being nearly destroyed by Dracula, finds strength again not through vengeance, but through the support of others and the reclamation of his faith. Mina, though targeted by the vampire, becomes the spiritual heart of the group, bearing both the suffering of the cross and the hope of the resurrection.

This communion of saints is not idealized. They weep, fail, and suffer, but they are held together by shared conviction and trust in God. The enemy they face is not flesh and blood, but a spiritual power, just as Paul writes in Ephesians 6:12. And they are clothed not in armor of iron, but in truth, righteousness, prayer, and the Word of God. As Jon writes in his journal, “it is in trouble and trial that our faith is tested—that we must keep on trusting; and that God will aid us up to the end.”

Female Dignity, Chastity, and the Battle for the Soul

Though they’re not his only victims, both Lucy and Mina are targeted by Dracula, but in different ways. Lucy is seduced (not sexually) by his influence slowly, her moral and spiritual guard lowered by flattery, confusion, and Dracula’s lies. Mina, by contrast, though also victimized, retains her faith and clarity of mind. Her spiritual dignity is preserved not by her own strength, but by the grace of God and the prayers of her Christian community.

Stoker does not engage in Victorian prudery, but he does make a theological point: purity is not merely sexual, but also spiritual. The defilement Dracula brings is not erotic but sacrilegious. The way Lucy is changed, desecrated, and then restored through a “vampire exorcism” (that doesn’t work) is meant to shock. She is a beloved daughter turned into a predator, but not beyond redemption. And in the mercy of God, her soul is released.

This battle for the soul—especially the souls of women—is not a side plot; it is the central drama of the novel. And in a world that trivializes the sacredness of the body—especially the female body—Dracula stands as a fierce defense of both the human and woman person as holy, beloved, and worth protecting.

Evil Defeated and the Theology of the Cross

The novel’s climax is not triumphant in the Hollywood sense. Dracula is killed, but not in a blaze of glory. He is quietly destroyed at sunset—trapped by the Host of the Eucharist, stabbed through the heart and beheaded, and then crumbles to dust. It is anticlimactic in one sense, but theologically perfect, because evil is not defeated by spectacle; it is defeated by faithful, hidden, painful obedience, which is perfectly culminated in Christ on the cross.

Dracula is undone by prayer, perseverance, and unity. The victory belongs not to warriors, but to witnesses. It is a theology of the cross—not the triumph of power, but the triumph of weakness borne in faith. His ultimate undoing begins with Christ’s body in the Host of the Eucharist. As Van Helsing says to Jon at the conclusion to the novel, “Thus we are ministers of God’s own wish: that the world, and men for whom His Son die, will not be given over to monsters, whose very existence would defame Him. He have allowed us to redeem one soul already [Mina], and we go out as the old knights of the Cross to redeem more.” Compare what he says to Ephesians 6:10-18.

And in the final scene—Mina and Jonathan with their child, named after each member of the fellowship—is a picture of the resurrection hope: that after the long night, the morning comes. That after evil is named and defeated, life can begin again.

Why Every Christian Should Read Dracula (Besides the Fact that the 1992 Film Sucks)

- It names evil for what it is. In a culture that softens sin, Dracula tells the truth: evil is personal, powerful, and parasitic, and it must be fought with truth, not compromise.

- It exalts the ordinary Means of Grace. Scripture, prayer, the crucifix, holy (baptismal) water, and consecrated bread are all weapons in the novel’s fight against darkness. These are not superstitions but visible signs of God’s power.

- It affirms the dignity of the body and soul. The vampire defiles what God makes holy; the Christian fights to restore that holiness through care, community, and piety.

- It offers a vision of the Church as the resisting body. The Church is not irrelevant; it is the only hope in a world of spiritual warfare. Dracula reminds us of the Church’s true identity—it is not a cultural club, but the Body of Christ (Ephesians 1:23; 1 Corinthians 12:12-27).

- It testifies to the cross’ final victory. Evil loses. Not because of human strength, but because of Christ.

Redemption from the Evil One

Forget the film. Forget the capes and fangs. Return to the novel. Read Dracula as it was written: a Christian story of good versus evil, where evil is real but not final, and where salvation comes not from man but from God. It is a time for Christians to reclaim this book—not to fear it or romanticize it, but to read it as a mirror of our own spiritual warfare; for we, too, fight the powers of darkness. We, too, walk through the valley of the shadow of death. And we, too, carry in our hands the Word that drives back the evil one, because the blood that saves is not stolen—it is given.

And it is stronger than death.