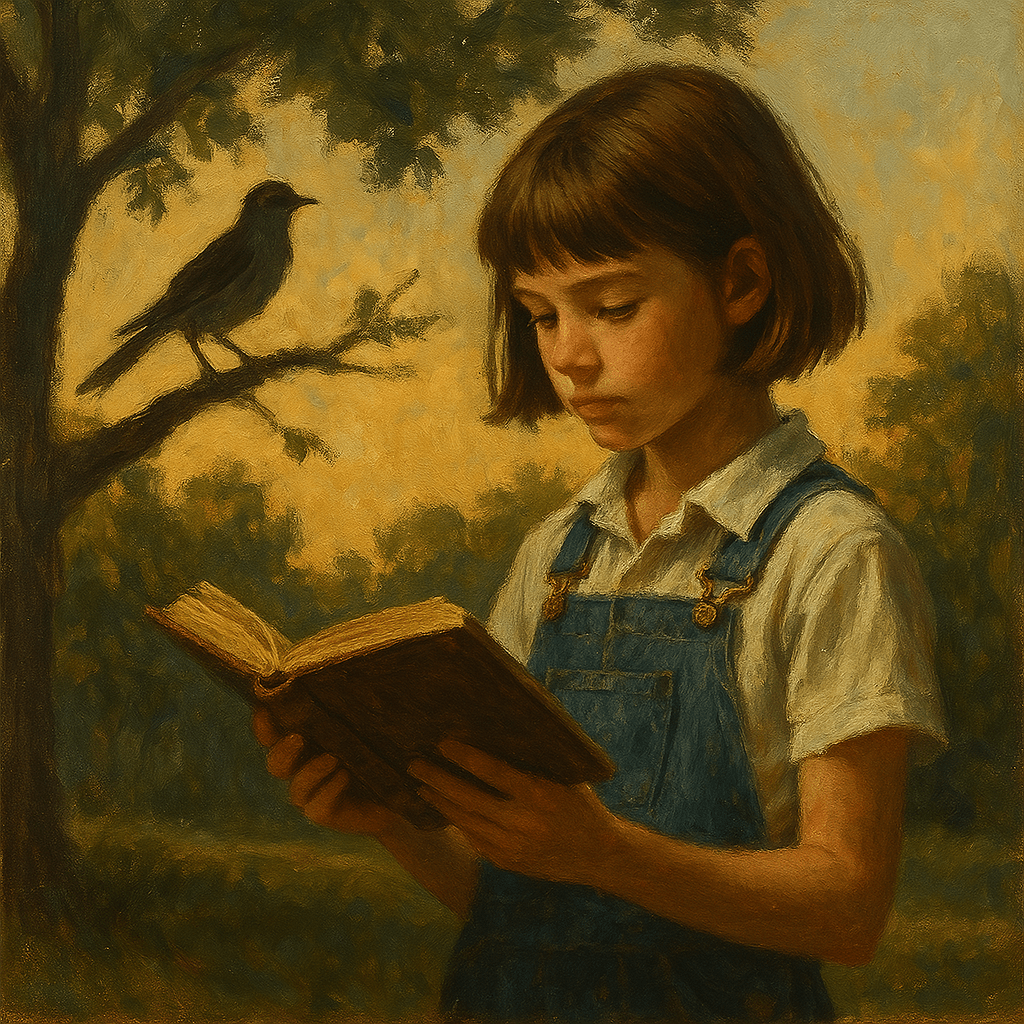

Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird has long been celebrated as a classic of American literature. But beyond its literary merit and historical significance, it deserves to be read—and re-read—by Christians as a profound meditation on justice, vocation, sin, and mercy. Written through the eyes of a child but shaped by the moral courage of an adult, the novel invites the Christian reader into a deeper reflection on what it means to live out faith in a world riddled with fear, prejudice, and injustice.

As a Lutheran pastor, I believe this book is not just good reading—it is good for the soul. It teaches us to weep with those who weep, to speak for those who have no voice, and to stand firm even when defeat seems inevitable. It is a story saturated with the tension between Law and Gospel and the visible and the hidden. It is, in many ways, a secular parable of the Christian life.

This is your spoiler warning.

Original Sin and the Brokenness of the World

At the heart of To Kill a Mockingbird lies the trial of Tom Robinson, a Black man falsely accused of raping a white woman, Mayella Ewell. Despite clear evidence of his innocence, Tom is convicted by an all-white jury. The injustice is brutal, heartbreaking, and predictable.

For the Lutheran, this is not surprising. We confess the human heart is corrupt—not simply mistaken, but curved in upon itself (homo incurvatus in se). Racism, prejudice, and cruelty are not cultural glitches; they are symptoms of the Fall. The trial of Tom Robinson exposes the systemic nature of sin, showing how entire communities can be blinded by fear and self-interest.

Atticus Finch, the lawyer who defends Tom, stands as a figure of righteousness—not because he is without sin, but because he acts in the face of it. He knows from the outset that he will lose. “Simply because we were licked a hundred years before we started is no reason for us not to try to win,” he tells his daughter, Scout. This echoes the theology of the cross. We do not love because it will succeed, but because Christ loved us (1 John 4:19).

Vocation and the Hidden Work of God

Lutheran theology emphasizes vocation—not simply one’s career, but all the stations/callings God calls us to fill (from the Latin vocatio for “calling”). God hides Himself in ordinary people doing ordinary things: parents raising children, teachers teaching, lawyers seeking justice. Atticus Finch embodies this beautifully. He is not flashy and he does not seek acclaim. He simply does his duty with integrity and grace.

His parenting is as much a part of his vocation as his legal work. He teaches Scout and Jem (his son) not just with words, but also by example. He is patient, disciplinary, and he explains the world without shielding them from its ugliness. In one scene, he tells Scout, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view… until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” This is not relativism; it is incarnational empathy.

God works through Atticus even when the world rejects him. His loss in court is not a failure in the eyes of God, but faithfulness. In Lutheran terms, he is a mask of God—hidden and bearing mercy in a broken world.

Law and Gospel: The Weight of Judgement and the Whisper of Grace

Throughout the novel, we see the Law doing what it does: it accuses, convicts, and kills. Tom Robinson is crushed by a system that reflects the fallen heart of man. Boo Radley is locked away, misunderstood, and maligned. Even Scout and Jem come face to face with the harshness of the adult world.

And yet, there are moments of grace—hidden, quiet, but real. The title of the book is drawn from Atticus’ admonition: “It’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.” Mockingbirds do no harm. They sing and give beauty, yet they are vulnerable. Tom Robinson is a mockingbird. In truth, Christ is the ultimate Mockingbird—blameless, rejected, and crucified.

When Scout finally meets Boo Radley and walks him home, she sees the world from his perspective. “Atticus was right,” she reflects. “You never really know a man until you stand in his shoes and walk around in them.” That is the moment the Gospel gives way to empathy—the knowledge that grace often appears in the lowliest of forms.

The Role of the Church and Its Silence

One of the more troubling aspects of the novel is the relative silence of the White church. The only vibrant community of faith depicted is the Black church, which welcomes Scout and Jem with open arms. There is no outcry from White pulpits over Tom’s trial—no moral clarity offered. The Church, it seems, has become just another part of the corrupt system.

This should trouble every Christian reader. We are called to be salt and light (Matthew 5:13-16), not chaplains of the culture. The Church must be willing to speak clearly about sin, especially when sin becomes respectable, institutional, or profitable.

Yet To Kill a Mockingbird also reminds us that the Church is more than its failures. Faith lives on in characters like Calpurnia, the quiet and steady housekeeper who embodies Christ’s love and dignity. It lives on in the Black congregation that sings hymns and clings to hope. It lives on in every act of mercy, however small.

Why Every Christian Should Read This Book

- It cultivates empathy. Christians are called to love their neighbor—not as an abstraction, but in flesh and blood. To Kill a Mockingbird teaches us to see the other, to listen, and to walk humbly.

- It awakens our conscience. The novel does not offer easy answers. It makes us wrestle with injustice, both systemic and personal. It calls us to examine our own hearts in light of the Law.

- It honors vocation. Atticus is a model of quiet, faithful service. His courage is not in victory, but in obedience. This is a powerful image for any Christian seeking to live faithfully in the various vocations they hold in a fallen world.

- It reveals hidden grace. In the midst of pain and failure, moments of love, kindness, and sacrifice shine through. The Gospel often comes not with trumpets, but with a whisper.

- It echoes the cross. Tom’s death, Boo’s isolation, and Atticus’ burden all point to the reality of suffering love (i.e., longsuffering). In this, they echo the greater story: the One who was despised and rejected for our sake.

The Mockingbird Still Sings

To Kill a Mockingbird is not a “Christian novel,” but it is profoundly thematic in Christian principles. It prompts us to see the world as it is: fallen, complicated, and unfair. And it prompts us to respond not with despair, but with faith, hope, and love.

Harper Lee gave us more than a courtroom drama; she gave us a lens through which to see our neighbors, our world, and ourselves. For the Christian, this is not optional; it is essential, because the Gospel is not just proclaimed in pulpits. It is also lived out in courtrooms, classrooms, kitchens, and front porches.

And sometimes, it sounds like a mockingbird’s song—gentle, persistent, and full of grace.