This is your spoiler warning.

To most, Stephen King is known as a writer of horror—monsters, murderers, and supernatural thrills. But what many overlook is that King is also a profound observer of humanity, sin, and suffering. Nowhere is this more evident than in his 1996 serialized novel, The Green Mile, a story that takes place not in a haunted house, but on death row, where a Christ-figure walks among the condemned, and where the echoes of the Gospel are strangely and deeply felt.

The Green Mile is a theological goldmine. While King may not be a confessional Christian, the questions his story raises—about death, (in)justice, miracles, evil, and mercy—are unmistakably spiritual and theological in nature. And in the heart of it all is John Coffey, a man with supernatural healing powers who is falsely accused, unjustly condemned, and voluntarily executed. His story bears a haunting resemblance to another Man falsely accused and crucified outside Jerusalem.

From a Lutheran perspective, The Green Mile deserves attention. It is a parable of Christ in the prison cell, an unexpected narrative of Law and Gospel, and a profound meditation on how death touches all of us—and how light breaks through, even there.

The Setting: Death Row as a Sanctuary of Suffering

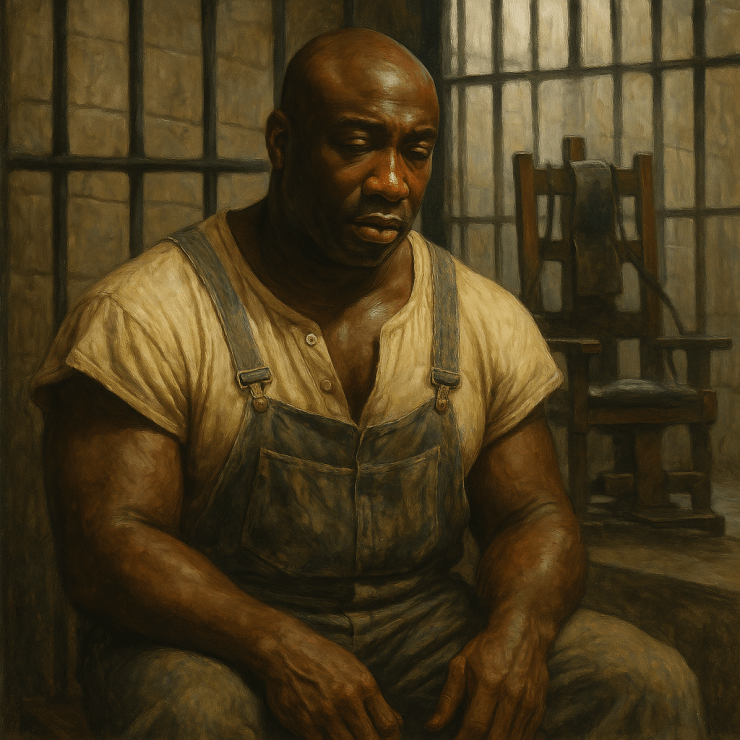

The story unfolds in the 1930s at Cold Mountain Penitentiary. The “Green Mile” is the moniker for E Block—death row, so called for the green linoleum floor inmates walk across on their way to the electric chair, “Old Sparky.” It is a narrow space of judgement, sorrow, and waiting. And yet, it is also—strangely—a place of grace.

Lutheran theology recognizes that God is often hidden in the very places the world sees as hopeless. Like a crucified man on a cross, God’s glory is often veiled in suffering and shame (1 Corinthians 1:26-28). So too, in The Green Mile, miracles happen in a prison. Life-changing events occur not in cathedrals, but in cells. This is the theology of the cross at work: God meets us in the lowest places.

The Christ-Figure: John Coffey (“Like the Drink, Only Spelled Different”)

John Coffey is the heart of The Green Mile. A towering Black man with gentle eyes and a stammering voice, he is convicted of the rape and murder of two young white girls. But from the beginning, it’s clear he didn’t do it. In fact, he is almost childlike—sensitive to suffering, disturbed by violence, and strangely gifted with the power to heal.

He heals Paul Edgecomb’s brutal urinary infection. He resurrects a dead mouse. He takes away the cancer of the warden’s wife. And by doing this, he absorbs their pain into himself—literally breathing in disease, hatred, evil, and death—and releases it in convulsions of agony and light. It is a visceral depiction of what Christ did for us.

The favored quote by John Coffey in the movie that’s not actually in the book is, “I’m tired, boss. Tired of people being ugly to each other.” It’s no accident that John Coffey’s initials are J.C. He is clearly a Christ-figure—falsely accused, misunderstood, a miracle-worker, gentle and innocent, bearing the sickness of others, and willingly walking to his death.

His crucifixion comes not by nails, but by electricity. And he does not resist it. Though the guards know he is innocent, he chooses to die—not because he is guilty, but because he cannot bear to live in a world so full of cruelty. Like Jesus, he is a sinless man sentenced for the sins of others. “Surely He has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows… He was wounded for our transgressions, He was bruised for our iniquities… and by His stripes we are healed” (Isaiah 53:4-5). Similarly, just before John Coffey is strapped to the wooden chair, he says, “They’re still there. Pieces of them, still in there. I hear them screaming.” And so, he bears their agony, much as Christ bore ours on the wooden tree of the cross. And though he sits in the chair willingly, fear is evident on his face, much as Christ experienced great anxiety in Gethsemane.

Coffey’s death is not a victory for the state; it is a sorrowful sacrifice, one that reveals the brokenness of human justice and the longing for a deeper mercy. In this way, King writes a parable of substitutionary atonement, even if unintentionally.

Law and Gospel on the Green Mile

The Green Mile is suffused with the Law—not only in the legal sense, but also in the theological sense. The condemned men—Delacroix, Wharton, Bitterbuck—face judgement. Their crimes are real. Their punishment awaits. Death is coming. And the reader cannot escape the gravity of it.

The Law, in Lutheran theology, confronts us with the reality of sin and death. It tells us we are guilty, that we cannot escape justice, and that we deserve to die. “For the wages of sin is death” (Romans 6:23a).

But then—the Gospel breaks through. In a dark cell, a condemned man is shown compassion, much as Jesus showed the condemned thief on the cross beside Him (Luke 23:39-43). A mouse is resurrected for Delacroix, much like Jesus resurrected Lazarus for Mary and Martha (John 11:38-44). A dying woman is healed, much as Jesus healed Jairus’ dying daughter (Mark 5:21-24, 35-43). A falsely accused man gives up his life, and those who witness it are changed forever, much as the Innocent One, Jesus, gave up His life and forever changed the lives of His Apostles who witnessed His death and resurrection, and then the whole world through their witness. “But the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Romans 6:23b).

This is how the Gospel works: not by denying the Law, but by fulfilling it through mercy. Paul Edgecomb, the head guard, begins the story as a man who believes in justice, and he ends it as a man haunted by mercy. His conscience is seared—not because he did the wrong thing, but because he participated in the death of an innocent man. It makes one wonder if this is how the centurion felt, who shouted, “Certainly this was a righteous Man!” (Luke 23:47).

Vocation: The Dignity of the Prison Guard

One of the most compelling parts of The Green Mile is its portrayal of the guards. Paul and his colleagues are not caricatures; they are flawed men in ordinary vocations, tasked with a grave responsibility: to usher men to their deaths with dignity, discipline, and care (with the exception of the wicked guard, Percy Wetmore, who abdicates his duty in his cruel treatment of the prisoners).

In Lutheran theology, vocation is the sacred calling to serve one’s neighbor in whatever station God has placed you—whether butcher, baker, mother, brother, daughter, teacher, even prison guard. Edgecomb treats the prisoners with fairness and compassion. He recognizes his job, though somber, is a calling to serve, to restrain evil, and even to comfort the dying. In a sense, he becomes a kind of pastor in uniform, walking the condemned toward their judgement. (In stark contrast, Wetmore is a wolf in sheep’s clothing; see Matthew 7:15-20).

This does not mean Edgecomb is without sin. His silence about Coffey’s innocence, his quiet resignation, and his inability to save the innocent all weigh on him. But through his grief, the novel shows the complexity of human responsibility under the shadow of the Law. And yet even here, the Gospel is present. Like the disciples eventually came to realize about Jesus’ death, perhaps he knew that although Coffey’s death was unjust, it was necessary.

A Supernatural Worldview

For all its grit, The Green Mile is unashamedly supernatural. Miracles happen, evil has a tangible presence, and justice is not merely about human law but about a higher, deeper reality. This stands in contrast to many modern Christian books, which shy away from the mystery and majesty of the unseen. But Scripture teaches us we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against spiritual powers (Ephesians 6:12). King’s narrative echoes this in its own way. There is more to this world than we can see. And sometimes, angels walk among us—unarmed, unrecognized, and wrongly condemned.

“Let brotherly love continue. Do not forget to entertain strangers, for by so doing some have unwittingly entertained angels. Remember the prisoners as if chained with them—those who are mistreated—since you yourselves are in the body also” (Hebrews 13:1-3).

Echoes of the Cross and the Resurrection

Though the novel climaxes with Coffey’s death, it does not end in despair. Paul Edgecomb lives on—physically, unnaturally long—and spiritually burdened but not destroyed. The final image is one of hope. He waits. He remembers. And he wonders whether he will see John again.

This, too, is Christian longing. “God will wipe away every tear from their eyes; there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying. There shall be no more pain…” (Revelation 21:4). We, like Edgecomb, live in a broken world where death seems to have the final word. But through stories like The Green Mile, we are reminded that death has been trampled, the innocent Lamb has died in our place, and that one day, we will not walk the Green Mile, but the golden streets of the New Jerusalem (Revelation 21:21).

When Stephen King Preaches Christ

No, The Green Mile is not a Christian novel in the conventional sense. But it is a profoundly Christian book in the theological sense. It compels us to weep, to wonder, to reckon with guilt and justice (and injustice), and to hope in something beyond the grave. In John Coffey, we see a shadow of Christ. In the prisoners, we see ourselves. And in Edgecomb, we see the ache of the conscience awakened by grace, and perhaps even our pastor who walks us to our grave as he teaches us to die well.