Rebecca F. Kuang’s Babel: Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution is one of the most theologically rich secular novels of recent years, not because it quotes Scripture or centers on Christ, but because it wrestles with a unique question: What happens when language is used not to communicate but to control and oppress? What happens when knowledge is used not to serve, but to dominate?

The novel is a deeply imagined alternate history in which the 1830s British Empire has expanded and secured its power through magical silver-working—a system that relies on translation and the subtle untranslatability between languages to produce energy and influence. In this world, the act of translation is not only academic, but also alchemical. Silver bars inscribed with paired words—say, in Latin and English, or Mandarin and Greek—capture the gap between languages and turn it into magical power.

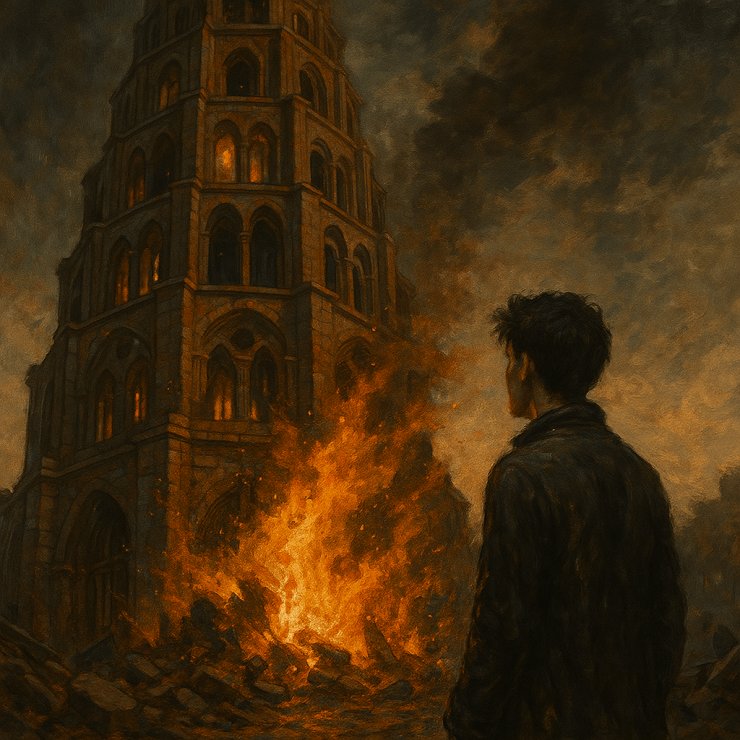

Babel, the tower-like translation institute of Oxford University, becomes the literal and proverbial center of British colonial strength. But as this dark academia unravels, it becomes clear this institution built on language is also built on exploitation, theft, and death. This novel is not Christian fiction. It is unapologetically political, sharply anti-imperial, and saturated with moral anger. And that is exactly why every Christian should read it.

This is your spoiler warning.

“Let Us Build a Name for Ourselves”: Babel as Empire

Kuang’s choice of title is no accident. She names her central institution Babel for a reason, calling to mind Genesis 11 where humanity unites to build a tower to the heavens. Kuang does utilize Josephus’ erroneous interpretation of the Tower of Babel—that it was their attempt to get closer to God rather than what the text actually says, which was their desire to make a name for themselves and disobey God’s command to multiply across the Earth (Genesis 11:4). However, I don’t consider this a true critique of the novel since Josephus’ error is commonly accepted among scholars, so it’s only accurate that the misinterpretation is employed at this fictional Oxford.

God confuses their language not because unity is inherently evil, but because this unity was rooted in pride and disobedience—in a godless desire for power. Kuang’s Babel does the opposite—it attempts to reverse the curse of Babel by mastering all languages. But in doing so, it recreates the same problem: a centralized power that uses language to play God.

What makes Babel such a compelling novel for Christians is the way it explores the weaponization of language. From the beginning, Scripture reveals that God’s Word creates. “Let there be light.” Christ Himself is the Logos—the Word made flesh (John 1:1-2, 14). But at Babel, language is severed from love, communion, and truth. It is used to dominate, self-justify, and extract.

Christians should be deeply unsettled by this because the sin of Babel is not ancient history. It is repeated in every empire that uses beauty to conceal brutality—in every nation that uses theology to bless conquest. Babel’s tower still rises today—in universities, corporations, and nations that exploit the knowledge and labor of the weak for the enrichment of the elite (e.g., “My body my choice,” “women’s rights,” and “abortion is healthcare” to justify the oppression of the unborn—autonomy becomes their irrefutable god and personhood is redefined).

Colonialism as Original Sin Repackaged

Kuang’s central critique is that colonialism is not a regrettable byproduct of empire—it is its foundation. The British Empire’s dominance in Babel is directly powered by the exploitation of foreign languages, peoples, and resources. The magic system depends on the tension between languages, but also between cultures. One must “own” the native tongue, even if one disdains the native speaker.

This echoes the real-world history of colonial missions, in which Christianity was often co-opted to justify conquest and forced assimilation into White European and, later, American culture. British colonizers brought the Bible in one hand and the rifle in the other. Kuang understands this pattern well and lays it bare. The Christian reader cannot avoid the parallels. We are reminded of how the Doctrine of Discovery, the transatlantic slave trade, and the carving up of Africa were all blessed by so-called Christians.

And yet, here lies the opportunity: Babel exposes not just the sins of the past but also the very mechanisms by which sin hides itself. It shows how institutions can appear beautiful—classical architecture, refined language, scholarly prestige—while concealing violence and oppression. This is the theology of the cross versus the theology of glory in narrative form. What looks noble is often corrupt. What looks weak—like those resisting from below—often carries the greater truth.

Robin Swift and the Burden of Resistance

The protagonist, Robin Swift, is a biracial orphan raised in England after the death of his Chinese mother. He is brought to Oxford to become a scholar by a mysterious benefactor, but he soon discovers he’s not there for love or education. Instead, he’s there because his language and academic labor serve the Empire’s needs.

Robin’s journey is tragic: his idealism is slowly broken, he tries to resist, he tries to reform the system, he even commits murder, and by the novel’s end, he chooses martyrdom: barricading himself within Babel, triggering a magical explosion that brings the entire institution crumbling down.

This ending is not clean. It’s not redemptive in the traditional sense, but it is cruciform. Robin chooses death rather than complicity. He sacrifices himself not to save the Empire but to destroy its ability to further harm.

From a Lutheran perspective, this invites reflection on vocation, sin, and sacrifice. Robin’s dilemma—how to live morally within a morally bankrupt institution—mirrors the questions many Christians face today: Can we work within corrupt systems? When and how must we resist? How do we faithfully enact change? What does faithful suffering look like? Robin’s choices are not perfectly righteous, but they are deeply human. And his story calls us not to romanticize purity, but to embrace the difficult work of repentance and courage.

The Necessity of Violence?

The subtitle of the novel—The Necessity of Violence—echoes throughout the book. I believe Kuang is not necessarily advocating violence for its own sake, but she does compel us to wrestle with the moral limits of peaceful resistance. When persuasion fails and peaceful protest is ignored, what then?

Christians are not called to revolution by sword. Our King triumphed not by killing His enemies but by dying for them (John 18:10-11). And yet, Babel forces us to reckon with the fact that peace built on injustice is not peace, and systems that do not hear the cries of the oppressed will eventually face their wrath. This is the Law doing its crushing work.

As Luther wrote in his commentary on the Magnificat, “[God] has always so guided the world that the lowly and despised have been exalted and the great and mighty put down; and so it goes until the Last Day” (LW 21:326). In Babel, that reversal comes not through piety, but through pain. Yet even in that, the Christian can see the truth that empires fall, Babels crumble, and those who mourn now will be comforted.

Reading Babel as A Christian

So, why should Christians read this book?

- To learn repentance. Babel is a mirror. It shows how good intentions can be complicit in evil. It forces us to ask how our faith, our institutions, and even our theology have served Empire more than Christ. Furthermore, the book compels us to face the role Christians played in both European and American colonialism and to condemn those actions.

- To hear the oppressed. The novel centers voices the Church has also ignored: the colonized, the silenced, the exploited. We are called to listen—not to agree with every conclusion, but to acknowledge every pain.

- To long for the Kingdom. Babel shows us the futility of earthly towers. It drives us to desire a city not built with hands (Hebrews 11:10)—a kingdom where every tribe and tongue is not translated into uniformity but gathered in harmony (Revelation 7:9-10).

The Tower Will Fall, But the Word Remains

In the end, Babel is not a hopeful novel, but it is a true one. Its hope lies not in victory, but in exposure—in the tearing down of illusions. And there, perhaps, it becomes most Christian, because the Gospel begins with tearing down, just as the veil of the Temple was torn to give us direct access to the Father (Matthew 27:51). The Law exposes. The cross offends. The Word kills before it raises.

But raise it does.

And so, we read Babel not to despair, but to learn what God opposes—and what He will redeem. We read it to hear the groaning of creation under injustice. And we read it to remember that Babel never lasts.

Only Christ does. Only His Word, which was not used to dominate, but to save.