I watched the above thought-provoking video recently, and I found it a decent presentation. Dr. Steven Schlozman’s basic premise is that horror gets us to ask difficult questions we wouldn’t otherwise normally ask, and therefore how we can better love each other. “We don’t like difficult questions unless somebody poses it in displacement.”

I’ve always enjoyed horror, especially in literature as an avid reader. Stephen King’s Cujo, for example, prompts us to ask questions about responsible pet ownership, emotional abuse, and proper communication in a marriage (at least in the novel). Schlozman presents the topic from a psychological perspective, which is helpful, but there’s a theological perspective as well in which we can appreciate this taboo genre.

Of course, the genre isn’t for everybody. Some might even go so far as to say that Christians shouldn’t watch or read horror. Obviously, I disagree with these people, because horror can help us ponder the Lutheran framework of Law and Gospel as well as our understanding of human nature in light of sin and redemption.

Confronting the Reality of Sin and Evil

The world is broken by sin (Romans 3:23), and horror allows us to explore this brokenness in a controlled, safe, and fictional setting. I say safe because rather than learning about the repercussions of not vaccinating our pets against rabies from personal injury or death, Cujo helps us ask those questions in a safe environment. One of the hallmarks of horror is that it exposes the depth of human depravity, the reality of evil, and even the demonic forces at work in the world (Ephesians 6:12).

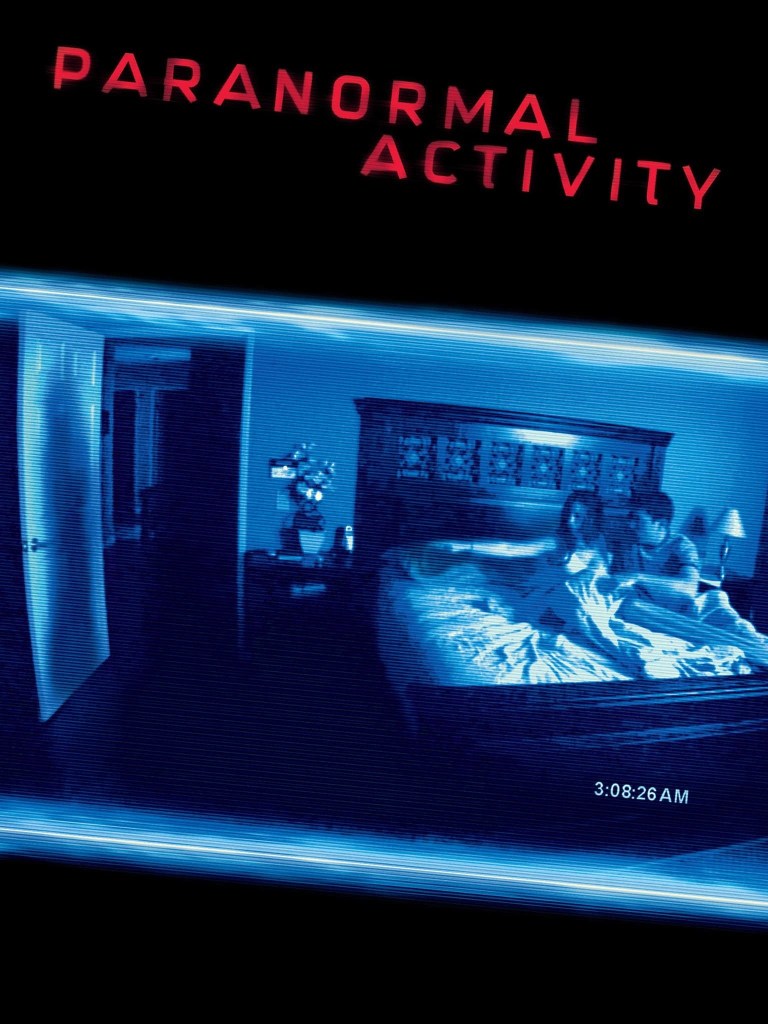

Like most other human beings, I jump and get startled at the occasional jump scare, but as an adult, I was never truly horrified until I watched the first Paranormal Activity movie in theaters when it was released in 2007. The jump scares were terrifying, and the intense suspense kept my adrenaline pumping throughout the entire movie, but what terrified me the most was the question it brought me to ask, “Am I in danger of demons?” This question stayed with me long after the movie ended.

This was long before I was a pastor, but my belief in demons is what made it so terrifying to me, as opposed to something like zombies because they aren’t real and never will be. I kept asking myself, “How do I know I’m protected against demons?” This is an important question for every Christian to ask. I’m not going to enumerate my discovery here, but the question eventually brought me to find comfort in my Baptism—that as a baptized child of God, I am possessed by the Holy Spirit, and I receive the Word and Sacraments regularly, so I am safe from demonic possession. Demonic oppression will occur from time to time (as it will for all Christians), but I do not need to fear physical harm from demons because of my status as a baptized child of God.

I’m not sure I would’ve asked this important question if I hadn’t seen such a horror movie. At the very least, I asked it and began exploring my faith more at an earlier age than most.

Our Fascination with Justice

Horror often portrays the consequences of sin, either through supernatural punishment (e.g., ghosts haunting the guilty) or through natural consequences (e.g., a serial killer enacting justice in a twisted way). I think one of the main reasons we like horror so much is because it usually portrays justice (or vengeance) at the end—the hero survives against all odds to exact justice against the horrible enemy, whether natural or supernatural. This resonates with our Lutheran understanding of God’s Law, which convicts us of sin and shows us our need for salvation (Romans 7:7-13). Horror can reflect this truth, even when it doesn’t offer a redemptive solution.

One of the common tropes of the horror genre is that people who lose their virginity are among the first to die. This might bring one to ask, “Should I be so promiscuous? What possible consequences could there be in premarital sex?” Horror movies really strike it home when Jason Voorhees, for example, hacks the former virgins into pieces, illustrating in a very provocative way the consequences of this sin: death. Which brings us to a further understanding that all sin leads to death (Romans 6:23). While their deaths are portrayed in horrible ways, Hell will be infinitely worse.

Horror also fills us with a sense of justice in a world where justice seems so rare. Stephen King’s The Green Mile is one of those stories that does this for us (the novel). While it brings us to ask questions about the imperfection of our current justice system and about the humanity of the worst criminals humanity produces, we see something more through the character John Coffey. He represents multiple things for the reader (or moviegoer). He’s definitely a Christ figure (which I won’t get into), he’s an example of how we shouldn’t judge a person by their appearance, and he serves as the plot device to show us how our justice system can be easily manipulated (especially for the time the story takes place in).

Most importantly, injustice falls on John Coffey’s shoulders (just as it fell on Christ, and it’s no coincidence that both their initials are J.C., but I digress). Convicted of a crime he did not commit, he becomes a victim of a prejudiced justice system. But despite this, justice still came for the man who actually committed the crime Coffey was convicted of. Even in a world of blatant injustice, true justice can still occur.

This is why we like and empathize with characters like Dexter Morgan from the show Dexter, even though he takes the law into his own hands and murders serial killers and people who’ve gotten away with murder or abuse (and even innocents to avoid capture and keep his beloved code), because he succeeds where the justice system fails. (I’m not saying what he did is right, just that it’s easy to empathize with his motives on a basic human level.) And this is why we like “the final girl” trope, no matter how much it’s overused, because we know that at the end of the movie, she will persevere and get justice, for “we also glory in tribulations, knowing that tribulation produces perseverance; and perseverance, character; and character, hope” (Romans 5:3-4).

Despite this, a horror book or movie with an ending that doesn’t go well for the protagonist can still be enjoyable because of the sad reality that there isn’t always a happy ending (e.g., The Blair Witch Project, Midsommar). As Christians, this can bring us to yearn even more for Christ’s Parousia.

A Longing for Redemption and Deliverance

Despite its darkness and gore, horror often includes a longing for deliverance, whether a survivor is overcoming evil (like Laurie overcoming the evil Michael Myers in Halloween [1978]) or justice prevailing in the end (like Paul Sheldon prevailing against the twisted Annie Wilkes in Misery). This can echo the Christian hope in Christ’s victory over sin, death, and the devil (1 Corinthians 15:55-57). In many horror stories, the protagonist must rely on something beyond themselves, mirroring our dependence on God’s grace.

In Stephen King’s IT, for example (the novel), both as children and adults, the characters relied on several things beyond themselves to overcome the evil Pennywise and finally find justice for all the horrors It wreaked upon the town of Derry: faith in their unity and imagination, the love of their friendship, the power of ritual and symbolism, and belief in a higher good (represented by the Turtle). This can bring us to ask certain questions about God, such as our unity to Him and to one another through Christ (Galatians 3:26-28; 1 Corinthians 12:12-27), the love of Christian fellowship/friendship (John 13:34-35; 1 Corinthians 13:1-13), the power of the rituals and symbolisms in our Lutheran tradition, and certainty that God—the higher Good—will always prevail.

Memento Mori: Remembering Our Mortality

This might seem morbid, but something we Lutheran pastors often repeat is that, besides administering the Word and Sacraments for the forgiveness of sins, life, and salvation, our primary job is to teach Christians how to die well. We are all going to die some day. As we heard quite recently on Ash Wednesday, “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return” (cf. Genesis 3:19). The time to come to terms with your mortality is not on your death bed, but well before then, rested securely on Christ our Rock. I have ministered to many people on their death beds who, despite their pain and fear, nevertheless exemplified tremendous faith because they knew they would be with Christ in Heaven and, even more, will be risen from the dead for all eternity.

During Lent—the season we’re currently in—we remember death not to despair, but to trust in Christ. That’s what the ashy crosses on our foreheads represent. Yes, we will return to dust, but the promise of what Christ did on the cross is that we will rise from the dead. “I am the resurrection and the life. He who believes in Me, though he may die, he shall live. And whoever lives and believes in Me shall never die. Do you believe this?” (John 11:25-26). The sooner we answer “yes” to this question before our death bed, the less afraid we’ll be of death and can sing, “O Death, where is your sting? O Hades, where is your victory?” (1 Corinthians 15:55). For as Christ has revealed to us, “This is the will of the Father who sent Me, that of all He has given Me I should lose nothing, but should raise it up at the last day” (John 6:39).

Horror forces us to confront mortality in a way that secular culture tries to ignore. Many people try to fecklessly elongate their life by dieting, exercising, and getting plastic surgery (not that the first two aren’t valuable). But horror punches us in the face with the frailty of life, pushing us toward contemplating where our true escape from death lies. As Christians, of course, that answer is Jesus Christ. Not healthy dieting, not your BMI, not lotion or essential oils, not Allah, not Buddhism, “Nor is there salvation in any other, for there is no other name under Heaven given among men by which we must be saved” but Jesus Christ (Acts 4:12).

Conclusion: Horror as a Genre of Law, but Without Gospel?

While horror powerfully explores sin, justice, and fear, it seldom provides the Gospel. This is where the Lutheran perspective sees its limits—horror can diagnose the problem but rarely points to Christ as the solution. In movies and books that deal with demons, for example, God’s Word is always portrayed as being insufficient in dealing with demons and the devil, and rather that one must turn to pagan practices like Voodooism, divination, or other witchcraft. However, as Lutherans, we can still appreciate horror as a means of understanding the reality of sin while always remembering the ultimate victory in Christ.

1 thought on “Why We Love Horror and Its Theological Utility”