As some of you reading this may already be aware, I was diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in November 2023. Since then, I’ve been on a journey of rediscovering who I am in Christ in light of my autism—learning things about my childhood, struggles in the recent past, and the present. My own edification has come from a combination of speaking with therapists, reading articles, and hearing from others’ similar experiences as mine. My goal in this article is twofold: (1) to help educate others about the realities and struggles of autism through my own story, and (2) to encourage others who are neurodivergent—specifically autistic—with the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

On that note, there are some terms you need to know before I begin, specifically the difference between neurodivergent and neurotypical. Many people, when they hear the word neurodivergent, misunderstand it to be neurodiverse. They are not the same.

Neurodiversity simply means everyone’s brain differences are natural variations—no deficits, impairments, or disorders. Neurotypical means someone whose ways of processing information and behaviors are seen as the standard. This term is interchangeable with allistic.

The opposite of this is neurodivergent, which is someone who processes information and behaves differently (divergently) than what is seen as the standard because their brains are wired in neurologically non-typical ways. Thus, neurodivergents include people with autism, ADD, ADHD, Down syndrome, dyslexia, and others. Everybody is neurodiverse, but not everyone is neurodivergent (which makes the statement, “We’re all autistic in some way” absurd, but more on that later).

My Experience on the Spectrum: Autistic Inertia & Monotropism

Autistic inertia is a phenomenon where an autist will struggle to switch between tasks, or certain states of being, to the point where they might feel frozen in place and unable to do anything else, even something they want to do. This inertia is an offshoot of monotropism—a relatively new term that virtually explains everything about the autistic experience.

Monotropism is the tendency to only be able to focus on or be interested in one or very few things at once. When I’m already doing something, that becomes the main thing I’m doing, and my brain will essentially latch onto that thing a lot tighter than a polytropic/neurotypical brain would (polytropism is the ability to attend to a number of activities or issues simultaneously, which is indicative of neurotypical behavior). For example, as a pastor, people expect me to socialize with them as soon as I walk into the church on a Sunday morning. But I’m in a monotropic state; I can’t do that. My mind is so hyper-focused on the task at hand (preparing for the Divine Service) that literally everything and everyone else around me just sort of disappears.

It is not something I choose to let happen; it is literally how my brain functions and I have no control over it. In fact, this was a huge problem for me as a child, causing me to fail many subjects in school because I could never remember the next tasks I was supposed to do since I get hyper-focused on whatever it is I’m doing. I’ve since learned how to use this to my advantage, writing down whatever the other tasks are and allowing myself to be hyper-focused one task at a time, further allowing me to be extremely efficient and thorough at whatever it is I do, which is how I became so successful in college and seminary. Interestingly enough, it was my experience in the Army that unintentionally taught me how to do this, but it makes sense why the Army fostered my monotropism. As an autist, I thrive on ritual and structure, and that is precisely what the Army is, so it easily became an environment for me in which I could thrive.

But I can’t translate this into social situations; it’s impossible. So, you can imagine how a congregation, unaccustomed to autistic individuals, might misinterpret their pastor’s behavior as unfriendly, or how a workplace might misinterpret a co-worker’s behavior as insubordinate, instead of what it actually is: neurodivergent. Perhaps a comparison would be sleepwalking. When someone is sleepwalking, the last thing you should do is force them to wake up. Similarly, forcing an autist out of their monotropic state is emotionally dangerous because it increases their anxiety and confuses them.

Add autistic inertia on top of all this—the difficulty of immediately switching between tasks. The transitions are what’s most difficult for autists. It’s not always a big change like going from home to work, or from home to the grocery store (which I experience). It depends on the autist, but it can be going from being asleep to being awake, lying in bed to standing up, being in the shower to being out of the shower, not eating to eating, doing a task to talking to people, all of which I experience, among other things.

Also related to this is what’s called pathological demand avoidance (PDA). It is a pattern of behavior where autists go to great lengths to avoid or ignore anything they perceive as a demand. Neurotypical individuals tend to view this behavior as being defiant, but what’s actually happening is a pathological response to anxiety, routine disruption, or transitioning from one activity to another not just because they perceive it as someone trying to control their autonomy but especially because it will trigger intense anxiety and/or sensory overload. So, they may refuse, withdraw, “shutdown,” or escape in order to avoid these stressful situations in the effort to retain their autonomy and avoid anxiety. Do not misunderstand pathological as meaning “insane” or “dangerous.” Something that is pathological merely means abnormal, a deviation, or a structural and functional change. And one’s pathology—whether it’s cancer, Alzheimer’s, or autism—cannot be controlled by the individual.

Think of it as intense self-care. Neurotypicals will know a situation will cause them anxiety but won’t avoid it. They might delay or procrastinate, but they won’t go through extreme measures to avoid the situation entirely. Autists do. For example, a person will say to me, “You should socialize more,” and I will think, “No, that will over-stimulate me,” and then avoid it altogether, even if I was already planning to do that anyway but on my own terms. One of my other favorites I’ve often been told is, “You should smile more,” and what’s my immediate reaction? To smile less.

As an autist who gets easily over-stimulated in social situations (more on that soon), I need to be allowed the time to prepare for every social interaction and to do it on my own terms. That being said, that does not mean I’m opposed to someone spontaneously walking into my office for pastoral care or just to talk. These one-on-one interactions are actually easier for me; it’s larger gatherings that terrify me. I do admit that at times, I get slightly frustrated only because it’s a disruption in my routine (I’m a sinner, after all), but I always gladly set aside whatever it is I’m doing to give them the attention they need. Pastoral care is something I’m very passionate about.

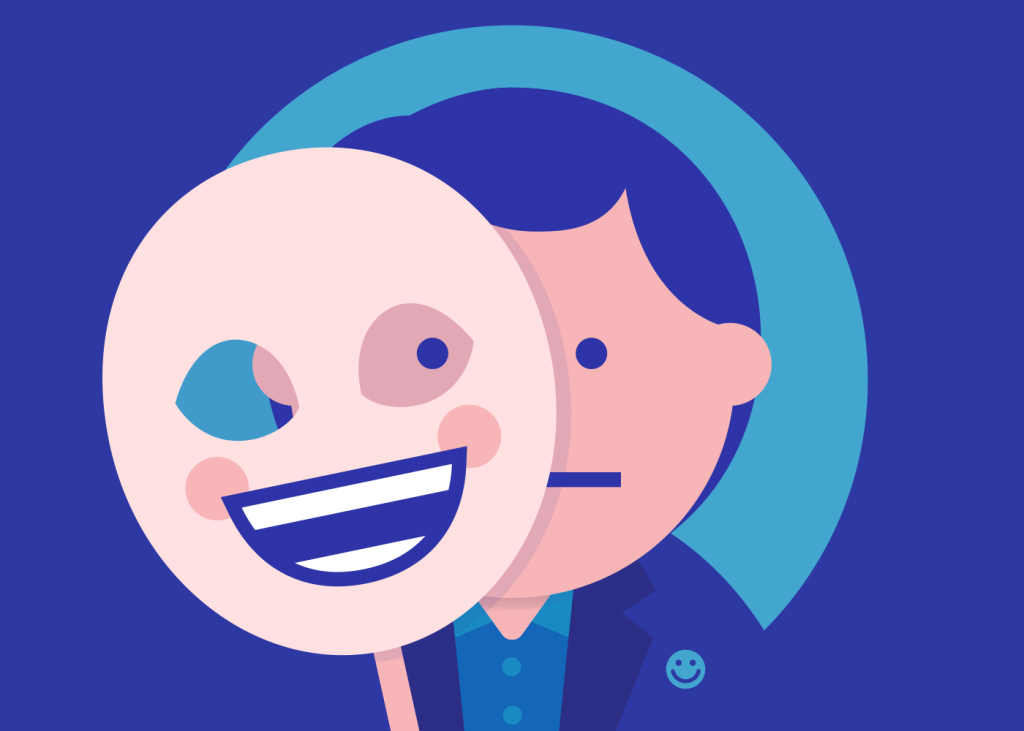

Masking

Probably the biggest thing about being autistic is what’s called masking. Masking is artificially performing behaviors that are more neurotypical by hiding autistic traits. For autists, masking seems like the only way to fit into society and to be accepted without being seen as “weird” or being judged for being different.

For example, I possess two traits that are common to autists: a flat affect in my voice and facial expressions. People have often criticized me of this my entire life, and it wasn’t until my diagnosis that I realized I’ve been masking my entire life. A flat affect is not the same as monotone; flat affect is little to no change in an autist’s tone of voice as well as facial expressions while expressing emotions. Additionally, what an autist might perceive as significant changes in modulation, a neurotypical person will not see it that way.

To make up for this, for my entire life I’ve been putting a lot of energy into over-exaggerating (what I perceive as over-exaggerating) my facial expressions and tone of voice to match what I think people want to hear. That’s one example of how I mask, and persistent masking leads not only to increased anxiety but often depression as well because we’re not being our true selves since we feel like we’re not allowed to be our true selves. We’re literally pretending to be someone we’re not.

If you’re neurotypical and you’re finding this difficult to understand, imagine people telling you—for your entire life—that the way you speak isn’t normal and you need to change that. Imagine people complaining that you don’t show enough emotion on your face when you receive a gift (and you actually really like the gift) and when someone relates an emotional experience (even though you do feel sympathy for them). Imagine being told you need to be like everybody else in social situations in order to be acceptable. How do you think that’d make you feel?

The greatest difficulty about masking is that while an autist is doing it, we become painfully and acutely aware of ourselves (this is where the over-stimulation I mentioned earlier comes in). It’s like a self-cognizance that becomes so detrimental because of how extreme it is. When I mask, I can’t be present in anything because I’m too focused on hyper-examining and over-analyzing every single thing I’m doing and every single thing that’s happening around me while it’s happening in order to be acceptable. I’m so aware of my existence that it takes me out of it—I literally become detached from the present experience. If I’m told to be more sociable, and I go and do that according to neurotypical standards, the purpose ends up being self-defeating because I can’t be present in the moment. Rather than enabling me to connect with people like it’s expected to do, I instead become detached from people.

There is a way for us to interact with people without masking. It is simply allowing us to be ourselves on our own terms—equal parts accepting and respecting the flat affect, the flat expressions (just because we’re not showing our emotions doesn’t mean we’re not feeling them), our stimming, our hyper-focusing (our monotropic state), routines, and so on.

How Autists Express Their Love

There are a lot of myths about autism that people falsely believe. For example, a neurotypical person might say, “But you don’t look autistic.” Just what the heck does autism look like, Greg? You can’t tell someone is autistic just by looking at them. Or they might say, “But you seem so normal.” Yes, Karen, welcome to masking. But I’m not going to cover the various myths just yet.

What I want to cover here is how autists generally express their love for someone because of the myth that we don’t know how to love or express our feelings. Depending on where someone falls on the spectrum, many people get the impression that autistic people are cold and unaffectionate because a lot of us don’t like physical touch (not so for me, to an extent) or perhaps struggle to communicate how we’re feeling (definitely true for me, unless it’s poetry or some other form of writing). That doesn’t mean we have no love to give or that we don’t feel emotions deeply. We simply express our love and care for people differently than allistic individuals—the way we express our love, among other things, is divergent, that is, different.

One of these ways is info dumping. This is when an autist shares (often overshares) about a topic they love and are extremely interested in, commonly their special interests (e.g., trains, lizards, dinosaurs, astronomy, etc.). For example, every time my wife asks me about something specific in a book I’m reading, or a video game (especially Destiny 2), I literally dump her with information—I launch into a monologue. Another example is that since I’ve obviously become very passionate about ASD since my diagnosis, I don’t hesitate to share who I am as an autist and some people view that as oversharing, but how is telling you a vital part of me oversharing? If I’m telling you about my autism, it’s because I care enough about you for us to have an honest relationship rather than hiding it, the latter of which would lead me to masking.

Or when a parishioner asks me a theological question or a simple question about the Bible, I info dump on them instead of giving them a short, simple answer. Some people might find this annoying or frustrating, especially if it’s repetitive (which I definitely do because I never know if I got the point across and I really really really really want to make sure that what I said made sense, because I honestly can’t tell). But for autists, it’s a form of us trying to connect and share something we care about with someone we care about.

The next example isn’t something I necessarily do but it’s something my wife does, who’s also autistic. One way an autist might express their love for you is by giving unusual but meaningful gifts. They will hold on to little bits of random information you’re least expecting them to remember. Like I said, my wife does this all the time for people she loves, and it’s always been one of the things I love most about her. For example, when we were first living together after we got married in Missouri, I remember telling her some things unique to my home state, Michigan, and how much I love Superman ice cream, and how much I missed it. One or two days later, I find Superman ice cream in the freezer (it wasn’t called Superman, of course, but it sure tasted like it). I did not expect her to remember such a small detail about me, and I definitely did not expect her to go out scavenging for my favorite ice cream flavor. Most of her gifts for my birthday, Christmas, and just random days are like this. She does this for others as well.

I’ve already covered masking, so when an autist unmasks around you, that means they feel safe and trust you enough to unmask in your company. There’s no way to describe this other than that you will immediately know they’ve unmasked because suddenly we’re not acting the way we usually do in public because we’re not masking. It’s like we’re an entirely different person, but we’re not a different person; we’re being ourselves. We become an entirely different person when we mask.

Another way is what’s called parallel “play.” This is when an autist is with someone and spending time with them but they’re each doing their own thing. Allistic people may not see this as actually spending time together because to them, spending time together is doing the same activity at the same time; but for autists it’s a valued way to spend time with loved ones, especially since socializing can be very draining. My wife and I do this all the time. She’ll be in her art room doing her own thing while I’m in another room reading a book, but neither of us view this as not spending time together. In fact, I will often go to her and tell her about something crazy in the book I’m reading and give her kisses to remind her how much I love her. If I share my space with you, you bet you’re one of the trusted people in my life whom I care about. There’ve been a couple other times when I’ve read a book while others were socializing, yet I viewed it as spending time with them whereas they did not since they’re neurotypical.

Lastly is shared experiences. When you’re sharing your own experience, we will often share our own. Many allistic people view this as us trying to “one up” them or “making it all about you,” but that’s not at all what we’re doing. We share our own experience in an effort to try to relate to you and what you’re saying. We’re simply trying to connect with you.

This list is by no means exhaustive.

Realities about Autism

Now that I’ve info dumped on you about what autism is for me, let’s talk about what autism is not.

Autism is not a disease or a mental illness. It is a neuro-developmental disability or difference. Our brains are literally wired differently than someone who’s neurotypical. It is also common for autists to live with some form of mental health issues (e.g., depression and anxiety), usually as a result of the struggle it comes with being an autistic person in a neurotypical society not willing to be understanding and make reasonable accommodations.

Autism is not an excuse. For example, some say I shouldn’t use my autism as an excuse to be a certain way if I ask for accommodations or even simple understanding. To say that is is just as insensitive as saying to someone who can’t walk not to use that as an excuse not to walk. Remember, it’s a neurological disability (autists are even protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act). Similarly, allistics will say, “Don’t make autism your entire personality.” I’m sorry, but it’s literally my brain functioning and reacting to stimuli differently. How can it not be my personality? If people can make sports their whole personality, I can make literally who I am my whole personality.

Autism is not an excuse; it is an explanation. When we do something you find annoying or frustrating and we explain why, we’re not saying we shouldn’t try to do it. We’re saying we are trying, and clearly it’s not enough. So, here’s an explanation so you understand it has to do with our brain wiring (e.g., why I can’t increase my level of sociability without increasing my anxiety). So, cut us a little slack and possibly even show us some empathy for what’s not within our control.

Autism is not caused by vaccines. People who don’t know anything say vaccines cause autism. The research on which this myth is based has been rejected and has long since been disproven by neuropsychologists.

Autism is not something you grow out of. An autist can seem more or less autistic (hence the earlier sentiment, “But you seem so normal”) depending on a number of different factors. It is not uncommon for autists to learn how to mask out autism, which means we may seem less autistic because we use learned behaviors to appear less autistic to fit into society. That does not mean we’re not autistic anymore. We’re literally acting. In cases like my adult diagnosed autism, it can be diagnosed late either because it was missed during our youth, or sometimes certain autistic traits become more pronounced (and vice versa) later in life, or a combination of both. For example, I had severe food aversion syndrome—a commonality among autists—when I was a kid because of the texture and presentation of certain foods. This has become less pronounced as I’ve gotten older. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve developed more adverse reactions to my routines getting interrupted and have developed more social anxiety because I’ve been masking for over three decades.

Autism is not a trend. Often, people will say, “It seems like every other person is on the autism spectrum these days.” If it seems like a trend, that’s because we understand autism a lot more than in recent decades, and the more we understand it, the more we realize it’s been missed in specific individuals. More and more adults are being diagnosed with some form of neurodivergence.

Not everyone is on the spectrum. Perhaps the most annoying myth is when people say, “I think we all have a little something.” This comes from a place of ignorance. You’re either on the spectrum or you’re not; there is no in between. Autism spectrum refers to a range of neuro-developmental conditions that affect individuals in various ways. ASD is characterized by a specific set of social, communication, and behavioral patterns, as outlined in diagnostic criteria. If everyone were on the spectrum, accommodations wouldn’t need to be made for neurodivergent people in a neurotypical world! When people say “we all have a touch of autism,” they’re being insensitive to an autist’s experiences and struggles in a neurotypical world.

Lastly, autism is not a result of bad parenting. This is a rather old myth that said it was a lack of closeness and connection between mother and child that made the child autistic. This myth is based on outdated and rejected research. Research today shows autism is probably hereditary and that people are most likely born autistic.

Meltdowns

Something else that needs to be understood is autistic meltdowns. This varies widely from autist to autist (remember, it’s a spectrum, not a straight line, or a puzzle piece as if we’re missing parts of ourselves), and some can be quite severe (such as self-harm), so I’m not going to touch on every single one of them—just the ones related to my experience.

For me, a meltdown can look like social withdrawal and zoning out/dissociation. This can be caused by a sudden change in routine or expectations or over-stimulation. If demands are made of me to be more sociable, I will eventually withdraw. For me, a meltdown can also be caused by social over-stimulation, masking for too long, and anxiety and depression that are common co-occurring conditions with autism. Another common experience for me is during a meeting, or sitting in a restaurant with friends or parishioners, and I’ll dissociate because of all the talking and various other sounds (over-stimulation). From the allistic’s perspective, this will look like I’m daydreaming or not paying attention. But I literally dissociate—I’m not aware of anything around me. My body is there, but my mind isn’t. It’s difficult to explain. This also happens when I’m masking while socializing, and I end up not remembering anything the person said.

So, how can you help? Keep your voice gentle and calm. Do not try to reason. For example, if I were to socialize on my own terms at a social event, then leave once I start to become over-stimulated, it would not be beneficial for someone to later tell me that I shouldn’t have left when I did. This has happened to me on numerous occasions throughout my life. The result? Increased depression and anxiety because I failed to understand what I had done wrong (in truth, I did nothing wrong).

Lastly, along with this, is giving appropriate time to recover. Again, this is different for every autist; this is simply how it is for me.

Other Things I Learned

Without diving into too much detail, here are a few other things I’ve learned about myself.

- Hyperlexia: Hyperlexia is common in autistic children, and this relates significantly to my childhood experience. According to WebMD, hyperlexia is “when a child starts reading early and surprisingly beyond their expected ability. It’s often accompanied by an obsessive interest in letters and numbers.” When I was in 4th grade, for example, I was told I had the reading level of a college student. I still write short stories to this day, and I first delve into writing stories as early as 1st grade because I would read a story and then be inspired to write something like it. I also love doing word searches and reading license plate numbers because of the patterns I recognize in them.

- Being Perceived: As Autism Chrysalis poignantly puts it, being perceived is “feeling bad when other people are around even when nothing bad is happening, even when they’re not doing anything to you, that just being perceived feels like too much pressure.” For many autists like myself, simply walking into a room where there are other people can drastically increase our anxiety level because we feel like we’re being constantly judged and criticized. This is likely because we’ve been criticized, shamed, and excluded because of our neurodivergent behavior for many years.

- Stimming: This widely varies from autist to autist. Stimming involves “self-stimulatory behaviors that involve repetitive movements or sounds” (source). Stimming for me is rocking from side to side, facial grimacing, nose scrunching, eye blinking, and finger tapping. The reason for stimming is for emotional self-regulation, especially when we’re feeling anxious and/or over-stimulated. At times, we may not even realize we’re doing it.

- Routines & Rituals: The routines and rituals will also vary, like everything else unique to the spectrum. For me, this would include taking the same exact route if I’m driving to the grocery store, church, and other places. I’ve developed an entire system of what order I wear my t-shirts, use my coffee mugs, and what I drink with every meal every day. When these routines are disrupted, I get extremely irritated, which is quite common in autism. I also have to eat my food in a specific order (e.g., vegetables first, then the mashed potatoes, then the protein, and save salad for last so the other food doesn’t get cold and the salad is cold anyway).

There are other traits I possess, such as some light sensitivity, echolalia (meaningless repetition of words or sounds), touch sensitivity (e.g., tags on t-shirts, long socks, dress pants), food aversion (e.g., texture and presentation), and some other things. But this should suffice.

The Good News of Jesus Christ for the Autist

I share my experience not only to educate others but especially to encourage anyone who’s neurodivergent and/or going through mental health issues because it is common for autism to come with co-occurring conditions of anxiety and depression, which has been my experience. It is rather unfortunate that autism often comes with discrimination, which I have experienced not only in my childhood but also my adulthood. A lot of people don’t want to deal with the challenges autism brings, whether they’re parents, an employer, or even people in the Church. Obviously that makes depression even worse, but it can also make one understandably angry because of the prejudice. But I don’t want to dwell on the negatives and prejudices of my experience. Rather, I want to share how the Gospel speaks to the autistic experience.

I’ve been learning more and more what Christ meant when He said to Paul, “My grace is sufficient for You, for My strength is made perfect in weakness” (2 Corinthians 12:9). (As a side note, Paul continues, “Therefore most gladly I will rather boast in my infirmities, that the power of Christ may rest upon me.” Similarly, I gladly boast of—or “overshare”—my autism and its limitations because it shows the power of Christ in me.)

Because of my decades of masking and the heightened self-awareness that brings, I am painfully cognizant of my limitations—my weaknesses. And because masking has disallowed me from being who I am for 34 years (my entire life), it has led to severe depression and anxiety, which has not always led to supportive responses from individuals. If you’re neurodivergent and relate to my experience, there is hope and comfort for you in Jesus Christ. I’d like to share some words from a sermon I preached that tackled these issues:

So, when we think, “I’m worthless,” we can look to our Baptism where God—the King of the whole universe—made us His dear children. We can look at the stars and the amazing new telescope of images that look like we’re looking through a kaleidoscope of God’s creation and think we’re insignificant compared to the infinite vastness of the universe, but it wasn’t the stars or planets or whatever whom God baptized, but you and me whom He made His children. Think of how precious children are to us; that’s how precious you and I are to God. Think of how your heart flutters and how giddy you get when you see your child or grandchild or any child—that’s how God gets when He sees you and me, only on an infinitely greater scale.

And when we think, “I have no reason to live,” we know this is a lie of the devil because he has been a liar and a murderer since the beginning [John 8:44], and Christ says otherwise when He gives us His body and blood in the Lord’s Supper, which not only gives us forgiveness of sins but also life and salvation! Whether or not you deserve to live has nothing to do with it, because Christ gives us His very life anyway; His very body and blood gives us His eternal life and His eternal righteousness, which is to say eternal worthiness.

The Lord has been teaching me to love myself and my autism. I remember seeing a short video on Instagram when a mother with her little son said, “So my son suffers with autism,” and without hesitation he said, “I don’t suffer with it; I just have it!” I love that. For my fellow autists and other neurodivergents, there’s a psalm that has stuck with me since my diagnosis: “I will praise You, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made; marvelous are Your works, and that my soul knows very well” (Psalm 139:14). I’ve always loved this psalm for the pro-life cause, but verse 14 just hits me differently now ever since my diagnosis.

Marvelous are His works. The Lord’s work includes His creation, and that includes you (“For You formed my inward parts; You covered me in my mother’s womb,” v. 13), which means you are marvelous. You are not an aberration; you are a marvelous work of God.

One last Scripture I’d like to share with my fellow autists is John 9:1-3, “Now as Jesus passed by, He saw a man who was blind from birth. And His disciples asked Him, saying, ‘Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?’ Jesus answered, ‘Neither this man nor his parents sinned, but that the works of God should be revealed in him.'”

As discussed earlier, being autistic is not a result of bad parenting, whether the mother or father’s sin. Neither is it the result of the individual’s sin. Rather, I firmly believe it is “that the works of God should be revealed in him.” We all know about savant syndrome in a small percentage of autists—those genius musicians, artists, and so on. Those are truly works of God in them. But not every autist is a savant. Every autist is given various vocations by God just like any neurotypical person. But even more, just like everybody else, a baptized autist is a baptized child of God—the work of God that buries and raises them with Christ (Romans 6:3-5).

I will always remember one member at the previous congregation I served who has a higher level of autism than I do. For his protection, let’s call him “Alex.” Alex requires more support than I do, but I don’t think I’ll ever forget how important the Divine Service is to him. Several times, his mom has told me how even when she doesn’t want to get up and go to church, Alex will urge her to take them to church. It’s part of his routine (and boy do I understand routines!). God displays His work in Alex in his strict adherence to routine, where Alex will receive the works of God in His Word and Sacraments administered to him for the forgiveness of sins, life, and salvation. What is often the hardest thing for neurotypical people to do—getting up for church—is the easiest thing in the world for Alex. That is truly the work of God.

Naturally, I’ve had people challenge me—including my own conscience—if I should be a pastor. If socializing is so difficult for me because I get over-stimulated, why should I be a pastor? Well, I point to what we just read from Christ, that the works of God might be revealed in me; and from Paul, that Christ’s power might be displayed in my weakness—that despite my limitations (which every man has), Christ still accomplishes His great work. Consider Moses.

Moses was terrible at public speaking. Remember what he said? “O my Lord, I am not eloquent, neither before nor since You have spoken to Your servant; but I am slow of speech and slow of tongue” (Exodus 4:10). Yet how did God respond? “Who has made man’s mouth? Or who makes the mute, the deaf, the seeing, or the blind? Have not I, the LORD? Now therefore, go, and I will be with your mouth and teach you what you shall say” (vv. 11-12). God knew Moses’ public speaking was lamentable, yet He called him anyway. It is true what they say: God does not qualify the called; He calls the qualified.

I have a Divine Call from God Almighty—from the Holy Spirit Himself, made evident at my ordination. Yes, I have autism. Yes, I socialize very differently than most people. But who is the one who creates people and human relationships? Is it not the Lord, who made man from dirt and ordained him to begin communities modeled after his marriage with woman? Just as the Lord was with Moses’ mouth, so He is with my person when I minister to the people whom He has called me to serve.

Finally, a word of exhortation from Dietrich Bonhoeffer on what he calls the ministry of bearing, which is helping one another bear our crosses:

[The Christian] must suffer and endure the brother. It is only when he is a burden that another person is really a brother and not merely an object to be manipulated. The burden of men was so heavy for God Himself that He had to endure the Cross… But He bore them as a mother carries her child, as a shepherd enfolds the lost lamb that has been found… In bearing with men God maintained fellowship with them. It is the law of Christ that was fulfilled in the Cross. And Christians must share in this law… what is more important, now that the law of Christ has been fulfilled, they can bear with their brethren.

Life Together, 100-101

Christ has called us to bear our cross as we follow Him (Luke 9:23), and sometimes that means helping others bear their cross. What that looks like is how Christ bore His. While He did bear it alone as He cried out Psalm 22, “My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me,” on His way to Calvary, He did not bear it alone for a little while. Simon of Cyrene helped Him for a bit. Therefore, when your brother or sister in Christ bears their cross of mental health—or whatever it is—do not stand there and gawk and scoff like the heathen bystanders did to Christ, but be a Simon and help them bear it for a little while, that they might bring it to Christ who says, “Come to Me, all you who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take My yoke upon you and learn from Me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For My yoke is easy and My burden is light” (Matthew 11:28-30). Otherwise, Satan the master thief wounds them and we pass them by like the merciless Levite on his way from the temple.

Bibliography

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Life Together. Translated by John W. Doberstein. New York: HarperOne, 1954.

2 thoughts on “What I’ve Learned about My Autism”